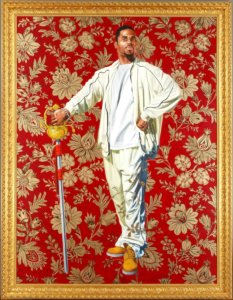

“Painting is about the world we live in. Black people live in the world. My choice is to include them. This is my way of saying yes to us.” –Kehinde Wiley.

“Willem van Heythuysen,” 2006

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, VA, has mounted a 14-year retrospective of the prolific artist, Kehinde Wiley. The show, A New Republic, first organized by the Brooklyn Museum, is comprised of some sixty large-scale compositions in oil and enamel, stained glass, and gold leaf on wood.

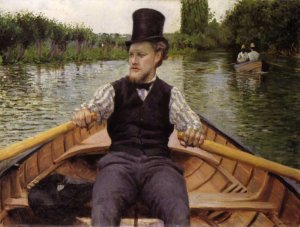

“Willem van Heythuysen,” 1625, by Frans Hals

Born in Los Angeles in 1977, Wiley now lives and works in Brooklyn, NY, drawing many of the models for his portraits from the streets of Harlem and his own neighborhood. Wiley tweaks our conception of art, art history, power, and identity by placing his subjects into the compositions of old masters such as Peter Paul Rubens and Jacques-Louis David.

“Morpheus,” 2008

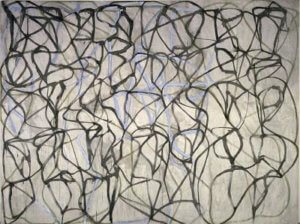

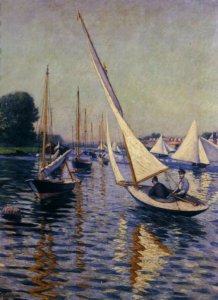

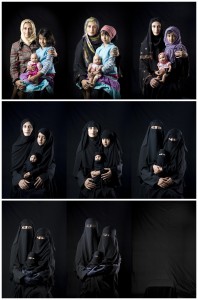

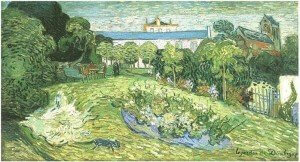

When you enter the show, you’re met with the eye-popping “Willem Van Heythuysen,” 2008. Riffing on the 1625 painting by Dutch master, Frans Hals, the artist gives us a new vision of a sword-bearing nobleman. Both men sport goatees, but our contemporary dandy wears snow-white athletic clothing instead of a stiff white ruff. Posed with the trappings of wealth and status of his day, Hals depicts the wealthy merchant in front of a luxurious tapestry, as does Wiley. The original van Heythuysen may have been a cloth merchant; clearly the tapestry is an important part of his world. Wiley poses the young man floating before deep red and gold brocade. The fronds of the floral motif begin to wrap themselves around the legs of the subject. Is there a double meaning here? Perhaps that the “backgrounds” of many of these young men threaten to ensnare them?

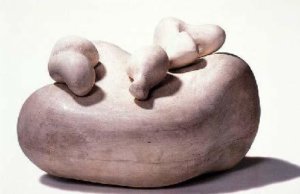

“Morpheus,” 1777, by Jean-Antoine Houdon

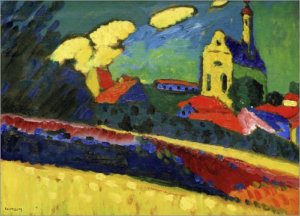

In the case of “Morpheus,” 2008, from the Down series, the background has taken flight. Based upon the sculpture of the same name by Jean-Antoine Houdon, our present-day god of dreams regards us with a jaded eye, looking up guardedly from under his stiff-brimmed cap, his wings clipped. He’s a come-hither hip-hop odalisque, while the white marble Morpheus’s eyes are closed in demure slumber.

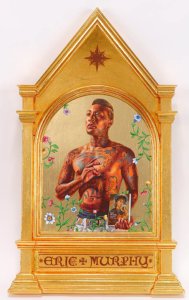

“St. Gregory Palamas,” (Eric Murphy), 2014

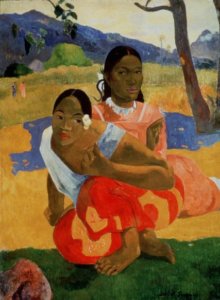

After the Byzantine icon, “St. Gregory of Palamas, 2014, gold leaf and oil on wood, pays tribute to Eric Murphy, gorgeously tattooed and holding the book, Icons and Saints. Angels appear on his shoulder and Eden-like flowers spring from the gold background. Unlike the ambiguous gaze of Morpheus, Eric Murphy seems transported, seeing something in the distant future, perhaps some vision of a world in which beauty and mystery coexist.

Wiley says, “…I wanted to create a body of work in which empathy and the language of the religious and the rapturous all collide into the same space.”

St. Gregory Palamas, Byzantine Icon

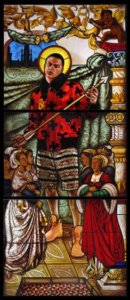

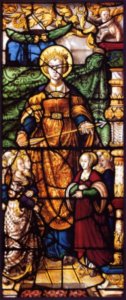

“St. Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs,” 20014, is one of a series of stained glass works (is there nothing this man can’t do? Or should I say, his atelier can’t do? Wiley reputedly has teams of artisans who complete the work once he’s designed and conceived it). Wiley’s Ursula—a young man— retains his 1535 doppelganger’s arrow, symbolic of love, erotic piercing, and sudden death on the streets. His attendants wear period-appropriate garments, while our contemporary figure wears shorts, a patterned jacket, and Timberlands, giving the viewer a strikingly vulnerable gaze which speaks of seeing too much too young. In the upper right corner, brown-skinned putti appear about to pull the whole thing down, hinting, perhaps, of the impermanence and sudden violence of urban life.

“St. Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs,” 2014

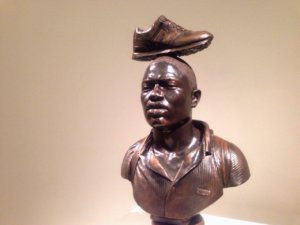

Also on view here is a series of bronzes. In “Cameroon Study,” 2010, Wiley evokes Charles Cordier’s “African Venus,” 1851, a lovely portrait bust of a young African woman formerly enslaved in France. Wiley’s contemporary African man appears put-upon, repressed—enslaved?—in a new way by the Nike sneaker atop his head.

“St. Ursula and the Virgin Martyrs,” 1532

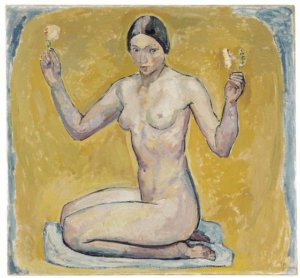

The final room of this exhibition is devoted to portraits of women. Wiley himself says that we “really don’t know who these women are.” They’re far from caricatures, but one wishes for more grounding in the here and now. Simply naming the portrait after the sitter (as with St. Gregory Palamas/Eric Murphy) would help to make them more accessible. “Princess Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha,” 2012, shows a beautiful woman in a designer gown (unlike the casual clothes of the men), her shoulders bare and burnished, her hair in an exaggerated up-do of epic proportion. Her counterpart in Sir Edwin Landseer’s 1839 portrait has equally mannered hair and, by contrast, alabaster skin. Both women face away from the viewer, presumably to display the intricate structure of the gowns, but the pose also to makes them inscrutable.

“Camaroon Study,” 2010

“African Venus,” 1851, by Charles Cordier

Reflecting on this show, I couldn’t help but think that the subjects of Wiley’s work would be the very last people on earth who could afford one of his paintings, let alone have the space to hang it. I hope that every now and then he gives these (mostly anonymous) people a sketch or photograph to commemorate sitting for him. With great appreciation the artist’s important message, wit, and verve, I came away wanting more recognition for the subjects. I was left with the question: why did the artist use the name of the historical painting or sculpture, and not the name, consistently, of the subject? Does this not deny them some fundamental aspect of his or her humanity? Or does Wiley mean to imply that their “slave names” are as irrelevant as the trappings of power of a bygone era? I’d love to ask him.

“Princess Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha,” 2012

“Princess Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha,” 1839 by Sir Edwin Landseer

Kehinde Wiley speaks about his work: http://kehindewiley.com/

The show will be up at the VMFA until September 5, 2016 http://vmfa.museum/exhibitions/exhibitions/kehinde-wiley-a-new-republic/

I’ve been wondering about the newly reopened Renwick Gallery here in Washington, DC. Long a cherished space, I was eager to see what the two year-long renovation of this Smithsonian museum—heretofore devoted to craft and decorative arts—had wrought. The first thing that jarred me was the bold white plastic sign along the exterior fence that announces “RENWICK” in giant sans-serif letters. In search of a photo, I came upon a number of articles that decried the placing of a garish LED sign on the front of the building, replacing the 1880s legend carved into the façade’s brownstone: “DEDICATED TO ART.” The new sign reads “DEDICATED TO THE FUTURE OF ART.” Museum officials say the sign is only temporary, part of the opening celebration. We can only hope. I’m also hoping the white plastic sign along the fence is temporary, but fear it’s not. The same logotype appears throughout the museum’s website and printed materials, no doubt in an attempt to shake off the lovely old building’s staid image. Strike one.

I’ve been wondering about the newly reopened Renwick Gallery here in Washington, DC. Long a cherished space, I was eager to see what the two year-long renovation of this Smithsonian museum—heretofore devoted to craft and decorative arts—had wrought. The first thing that jarred me was the bold white plastic sign along the exterior fence that announces “RENWICK” in giant sans-serif letters. In search of a photo, I came upon a number of articles that decried the placing of a garish LED sign on the front of the building, replacing the 1880s legend carved into the façade’s brownstone: “DEDICATED TO ART.” The new sign reads “DEDICATED TO THE FUTURE OF ART.” Museum officials say the sign is only temporary, part of the opening celebration. We can only hope. I’m also hoping the white plastic sign along the fence is temporary, but fear it’s not. The same logotype appears throughout the museum’s website and printed materials, no doubt in an attempt to shake off the lovely old building’s staid image. Strike one.

The interior of the graceful old building is painted shades of chilly gray causing the elaborate moldings, cornices, and flourishes to withdraw in the face of the “future” of art, that bracing, challenging, whup upside the head that is the new direction of the Renwick.

The interior of the graceful old building is painted shades of chilly gray causing the elaborate moldings, cornices, and flourishes to withdraw in the face of the “future” of art, that bracing, challenging, whup upside the head that is the new direction of the Renwick.

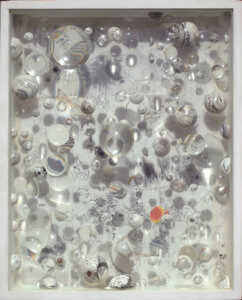

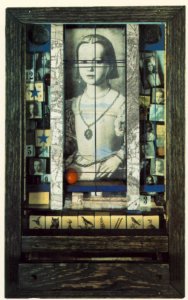

“In the Midnight Garden,” by Jennifer Angus is more than a little creepy. The artist has created stiff repeating floral wall patterns and day-of-the-dead skulls out of insects – yep, those are real bugs—and washed the walls with cochineal pink. In the center is an old chest of drawers, topped by a wasp’s nest and filled with curiosities: more bugs, buttons, feathers, tiny books, artificial fingernails. This Joseph Cornell-like piece smelled musty, like grandma’s attic, a pleasant, evocative scent that drew me in. I tried not to look too hard at the six-inch dead critters pinned to the walls.

“In the Midnight Garden,” by Jennifer Angus is more than a little creepy. The artist has created stiff repeating floral wall patterns and day-of-the-dead skulls out of insects – yep, those are real bugs—and washed the walls with cochineal pink. In the center is an old chest of drawers, topped by a wasp’s nest and filled with curiosities: more bugs, buttons, feathers, tiny books, artificial fingernails. This Joseph Cornell-like piece smelled musty, like grandma’s attic, a pleasant, evocative scent that drew me in. I tried not to look too hard at the six-inch dead critters pinned to the walls.

Yesterday I took a fresh look at this vibrant museum on Washington’s National Mall. The third floor galleries have reopened after renovation, and, in celebration of the museum’s 40th anniversary, an installation—At the Hub of Things: New Views of the Collection—presents some sixty works in various media from the permanent collection.

Yesterday I took a fresh look at this vibrant museum on Washington’s National Mall. The third floor galleries have reopened after renovation, and, in celebration of the museum’s 40th anniversary, an installation—At the Hub of Things: New Views of the Collection—presents some sixty works in various media from the permanent collection. Designed by Gordon Bunshaft—the architect also gave us the elegant Lever Building in New York City—the cylindrical building didn’t immediately wow the critics, or DC’s residents, for that matter:

Designed by Gordon Bunshaft—the architect also gave us the elegant Lever Building in New York City—the cylindrical building didn’t immediately wow the critics, or DC’s residents, for that matter: