John Singer Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends

“Edouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron,” 1881

Imagine you’ve been invited to a gathering hosted by the famous American expatriate painter John Singer Sargent (1856-1925). Here you meet his teacher, his patrons and their children, as well as his close friends—painters, writers, actresses, musicians, and dancers. You’re free to mingle with—even stare at—these storied creatures, among them, Claude Monet, August Rodin, and Robert Louis Stevenson. In fact, staring is welcomed. Selfies, however, are not encouraged. Where does this sparkling gathering take place? In Gallery 999 of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. You’re invited too—until October 4, 2015 when this exhibit of 92 works, organized by the National Gallery of Art, London, in partnership with the Met, closes.

“Ramon Subercaseaux in a Gondola,” 1880

While perhaps best known for his elegant society portraiture (who doesn’t love Madame X and her storied dress strap?), Sargent painted many informal, non-commissioned works which are often experimental and reveal haunting psychological complexity.

The arresting child duo, “Edouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron,” 1881, shows Sargent’s ability to take a potentially cloying Victorian subject and turn it into a surprisingly penetrating study. Marie-Louise’s unyielding gaze hints at her future as a prominent literary figure. The brother takes a secondary stance, turning to look over his shoulder at the viewer, as if only half in the picture. Marie-Louise is said to have been a piece of work; we learn that this picture took 83 sittings with many battles over the child’s costume and hair-do. Who would blame Edouard if he wanted to bolt? And what forbearance it must have taken our young master (Sargent was only 25 at the time) to complete this large, lush canvas. Worth it, I’d say.

Ramon Subercaseaux and his wife Amalia, were great supporters of Sargent’s career—a “young couple with progressive tastes.” A lovely portrait of Amalia at the piano hangs near “Ramon Subercaseaux in a Gondola,” 1880. The artist captures the shifting quality of light in that fabled city, as his sitter bobs up and down, evidently making notes before a meeting somewhere in Venice.

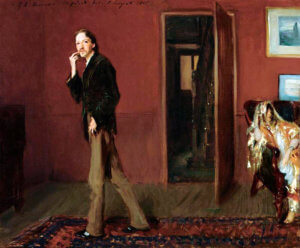

“Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife,” 1885

A most curious portrait, “Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife,” 1885, hints at volumes. Stevenson himself said the painting was “…too eccentric to be exhibited. I am at one extreme corner; my wife, in this wild dress, and looking like a ghost, is at the extreme other end…all this … with that witty touch of Sargent’s; but of course, it looks dam [sic] queer as a whole.” What went on in Sargent’s mind as he made this composition? Stevenson appears to be caught mid- sentence, with an uncertain gait and Ichabod Crane-like demeanor, while the veiled wife, Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne, appears to sulk in the corner. Stevenson has been quoted as saying that marriage to Fanny left him “limp as a lady’s novel,” while Sargent has posed her as an afterthought, practically out of the picture entirely.

“Garden Study of the Vickers Children,” 1884

From the gloom and sexual ambiguity of the Stevenson picture, we come into the full sunlight of “Garden Study of the Vickers Children,” 1884. Reminiscent of the enchanting “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose,” (not on view here), Sargent has captured the charm and sweetness of these children, but skews the perspective so that they’re viewed from above, with the lilies appearing to fall from the sky. As in the Stevenson portrait, Sargent aligns his subjects off-center, but with an entirely different effect.

“An Out-of-Doors Study,” 1889

How expressive Sargent’s portraits of fellow painters are! Of course he totally gets what they’re doing and conveys abounding respect and admiration for the act of painting. Look at the hand in “An Out-of-Doors Study,” 1889. What precision and intent! The hand belongs to his friend Paul Helleu, shown working outside in the lush Cotswolds, with his wife Alice lounging at his side. Another psychological contrast is set up between Helleu’s focused concentration and his wife’s seeming boredom. Sargent sets his subjects informally, as if caught in the moment and not posed, far away from the manicured parlors of his society portraits.

“Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy,” 1907

A later work, “Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy,” 1907, pictures Sargent’s friend Jane Emmet de Glehn and her husband, Wilfred. Sargent traveled widely, experimenting on these travels with outdoor painting. Here he affectionately portrays his subjects with a flourishing brush that catches the vivid Italian light. Once again, we detect a subtle disconnect between husband and wife. Of the picture, Jane says, “…a most amusing and killingly funny picture. I am all in white with a white painting blouse and a pale blue veil around my hat. I look rather like a pierrot, but have a rather worried expression as every painter should who isn’t a perfect fool, says Sargent. Wilfred is in short sleeves, very idle and good for nothing, and our heads come together against the great ‘panache’ of the fountain.”

“Isabella Stewart Gardner,” 1888

In a room devoted to American subjects, we meet “Isabella Stewart Gardner,” 1888, Sargent’s friend and patron. Mrs. Gardner had seen the radical “Portrait of Madam X” (whose daring presentation nearly derailed Sargent’s career), and wanted something similarly striking and non-conformist. Founder of the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston (where this painting hangs today), Gardner cut a bold figure in Boston society and is reputed to have attended a staid symphony performance wearing a headband that read, “Oh, You Red Sox!” I love this full-length vision of a woman ahead of her time: Her body is reduced to an almost abstract black shape, her head silhouetted against the halo of the tapestry behind her, and her alabaster décolletage is luminous. Although the image has a sacramental quality, Jack Gardner, her husband, insisted the portrait not be hung in public during his lifetime.

“Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth,” 1889

Last, but far from least, is “Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth,” 1889. This acclaimed Shakespearean actor played the role in Henry Irving’s production at the London Lyceum with Sargent in attendance. Her jaw-dropping costume was made from 1,000 beetle wings. In the painting, Terry is caught placing a crown on her head after the murder of Duncan, the Scottish king, although, we learn, this is not part of Shakespeare’s play. But who could resist that look of tragic triumph on her face, not to mention the glinting of thousands of beetle wings?

After spending hours in the company of Sargent’s fascinating friends, I was agog at his many talents: his skill rendering light, fabric, skin, nature; the easy freedom with which he moved from salon to informal portraiture; his extraordinary ability to capture psychological nuance. I was inspired to learn more about Sargent, whose enigmatic presence flickered throughout the show like a darting will-o-the-wisp. Next on my reading list: “John Singer Sargent: the Sensualist,” by Trevor Fairbrother.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!