Leger: Modern Art and the Metropolis, Philadelphia Museum of Art

“Smoke Over Rooftops,” Fernand Leger, 1911

Philadelphia’s Museum of Art’s massive show, “Leger: Modern Art and the Metropolis,” brings to mind Banksy, the poltergeist graffiti artist who bombed New York City recently with what has been described as a brilliant self-promoting PR campaign by some and a cleverly creative outburst of ephemeral art by others. Either way, the art (or vandalism, if you prefer) could not exist without the city as canvas.

And so it is with Fernand Leger (1881 – 1955) and his 1920s Paris circle. The metropolis—its movement, mechanization, hustle, clamoring billboards, buildings reaching skyward—shaped their ideas about art, artists, and modern life. The show opens with film footage of the Eiffel Tower made in 1900 by Thomas Edison. As the viewer rises with the camera, the city’s streets, buildings and parks flicker behind the geometric girders in a surreal montage—a fitting introduction.

“The City,” Fernand Leger, 1919

Nearby hangs “Smoke over Rooftops,” 1911, Leger’s first Paris cityscape—the view from his studio. Billowing smoke rises over the hard edges of the rooftops. Only nineteen when he first came to Paris, Leger encountered there an upheaval of technology: telephones, radios, the press, electric lights, and more.

After recovering from being gassed in the Great War (Leger went to the front for four years), he returned to “gobble up Paris” and “stuff it in my pockets.” Declaring that he “got myself out of the grays as quickly as possible,” he created “The City” in 1919. Owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “The City” is the centerpiece of the show. This large piece (about the size of a cinema screen of the day) reveals none of the moody atmosphere of the earlier work. Instead, the intentionally horizontal composition hustles us along, as if down the street. Meant to be viewed like a billboard, each element appears to be equal in importance: the scaffolding, the pole, the signs’ punchy colors.

“Razor,” Gerald Murphy, 1924

By drawing on contemporary advertising images—here the recently invented safety razor—Gerald Murphy’s “Razor,” 1924, had enormous influence on later painters, especially pop artists in the 1960s. Murphy, a “Lost Generation” compatriot with F.Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, et al, hosted Leger on his first trip to the United States in 1931. The accompanying notes tell us that in this image Murphy intentionally exploited the French view of America as being “hyper-modern and mechanized.”

“Ballet Mecanique,” Fernand Leger, Dudley Murphy, Man Ray, 1924

For this viewer, the 1924 experimental film produced by Leger and film maker Dudley Murphy, with help from Man Ray, was a surprise that was worth the price of admission. A Dada tour de force, its riot of images is enlivened by the accompanying music, which used mechanized player pianos, airplane propellers, electric bells and sirens. While many of Leger’s paintings appear to this eye as flat, orderly, and a tad sterile, this film succeeds in bringing the spirit of mechanization and modern life together in a radical-for-the time work of art. Take a look: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ez0LuU-Mg34

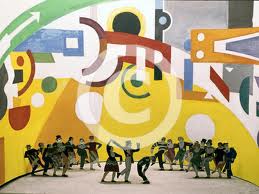

Curtain from “Skating Rink” ballet, Fernand Leger, 1922

Leger, a lover of all mass entertainments—the circus, skating rinks, theater—collaborated with the Ballets Suedois on “The Skating Rink,” 1922. Watercolor designs for the ballet’s costumes hang before a curtain which was recreated from the original 1921-22 design by Leger. In choreography also inspired by Leger, the dancers move in stilted, jerky ways that would seem at odds with the gliding, elongated movement of ice skaters.

“Model for Private House,” van Doesburg and van Eesteren, designed 1923, built 1982

The final room—devoted to “space”—gives us the utopian vision of Leger and his followers, as embodied in De Stijl architects Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren’s “Model for a Private House,” 1923, reconstructed, 1982 by Tjarda Mees. The architects thought of a house not as an enclosed cube, but as a series of intersecting planes painted in bright Mondrian colors which would create spaces that opened up to the environment as well as sheltered its inhabitants.

“Composition for Hand and Hats,” Fernand Leger, 1927

“Composition for Hand and Hats,” 1927, shows us how far Leger has come from the earlier smoke and rooftop composition. This cerebral composition carries, at least for this viewer, none of the emotional wallop found in some of Leger’s contemporaries, among them (and also on view here): Piet Mondrian, El Lissitzky, Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay-Terk, Pablo Picasso, Le Corbusier, Francis Picabia, and Marcel Duchamp. The gathering of so many important artists is impressive and gives the viewer a heady dose of the ideas and influences at work of the time. Whether the curators’ intention of revealing Leger’s painting, “The City,” as the impetus for this outpouring is still, in my view, an open question.

Go see for yourself! The show will be on view until January 5, 2014.

Learn more here:

http://www.philamuseum.org/exhibitions/766.html

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!