A Democracy of Images: Photographs from the National Museum of American Art

Just under the wire—I managed to see this show at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art, the Portrait Gallery’s conjoined twin museum, before it closed January 5. The title of the show—marking the 30th anniversary of the American Art museum’s photography collection—comes from Walt Whitman, who believed that photography was an ideal new medium for the expression of the peculiarly American democratic spirit. Ranging from daguerreotypes to contemporary new printing techniques, the images shown ranged from traditional documentation—portraiture, odd genre scenes from pre-civil war South, even mug shots—to experimentation, and all the possible permutations in between.

“Patriotic Boy with Straw Hat,” Diane Arbus, 1967

The show was organized by category: American Character, Spiritual Frontier, America Inhabited, and Imagination at Work.

An easy choice for the American Character section is Diane Arbus’s “Patriotic Boy with Straw Hat,” 1967. With his sweet big ears and empty eyes, this fellow seemed an easy target for Arbus’s acerbic and mocking eye. Too easy a target, in my view.

“World Trade Center Series,” Kevin Bubriski, 2001

Kevin Bubriski’s searing image from his “World Trade Center Series,” 2001, hits the viewer with the raw emotion of those awful days. Rather than focus on the falling towers or their smoldering ruins, Bubriski turned his lens on the spectators whose shock and horror mirror our own.

Annie Leibovitz’s “Marian Anderson’s Concert Gown,” 2010, printed 2012, is strangely moving. Made of five different images, it reads as a kind of funerary relic. The dress, tagged #35 (why?) becomes anonymous unless you know Marian Anderson’s body lived and sang inside it. Flowing from right to left, the fabric, with its red swath, appears to wave, flag-like. This odd combination of alive/dead, clothing/relic, specific/general, personal/anonymous makes the image absorbing. As you take it in, you see Marian Anderson singing on

“Marian Anderson’s Concert Gown,” 2010, printed 2012, by Annie Leibovitz

the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and, while Anderson didn’t wear the dress on that auspicious day, you suspect the artist intended the memory to pop up.

“Butte, Montana,” 1956, by Robert Frank

In 1954, Swiss-born Robert Frank applied for a Guggenheim fellowship to create an “observation and record of what one naturalized American finds to see in the United States.” Iconic photographers Walker Evans and Edward Steichen wrote references. Frank got the grant, and headed out in a used Ford to photograph life in America. I’m not sure if this moody image—“Butte, Montana,” 1956—is part of Frank’s brutally unsentimental series of resulting from this road trip, but I suspect it is. Published as “The Americans,” in 1959, the book, both reviled and revered, had a profound impact on the direction of modern photography and inspired legions of photographers, Ed Ruscha and Joel Meyrowitz among them.

“Tricycle (Memphis)”, around 1975, printed 1980, by William Eggleston

Pioneering color photographer, William Eggleston’s “Tricycle, Memphis,” 1975, printed 1980, echoes Frank’s vision of off-the-grid America, but now in a bright bleached palette, a distorted child’s eye view of an anonymous suburban enclave. The placard accompanying this photograph tells us that Eggleston started experimenting with color photography in the mid-60s and printed this image as a dye transfer print, a method usually used for advertising and fashion, with the intent of making it appear as an amateur photograph.

“Albuquerque, NM,” 1958, printed 1974, by Garry Winogrand

Hung next to “Tricycle,” is Garry Winogrand’s “Albuquerque, NM,” 1958, printed 1974—a genius pairing. “I photograph the world to see what the world looks like photographed,” Winogrand enigmatically said. For this haunted image, he used a pre-focused snapshot camera to create “the illusion of a literal description of how a camera saw a piece of time and space.”

In the Spiritual Frontier section, Eadweard Muybridge’s “Valley of the Yosemite from Union Point,” 1872 captures the grandeur of the West—and Manifest Destiny. Amusingly, we learn that the photographer was known to chop down trees to get the

best shot and often went to “points where his packers refused to follow…”

“Goodyear #5, Niagara Falls, NY,” 1989, by John Pfahl

The sublime “Goodyear #5, Niagara Falls, NY,” 1989, by John Pfahl was shot as part of a project focusing on old refineries and power plants in which he found a “transcendental connection between industry and nature.” Indeed.

“Cold Day on Cherry Street,” 1932, by Robert Disraeli

America Inhabited gives us this beautiful 1932 image by Robert Disraeli, “Cold Day on Cherry Street,” a perfect embodiment of photography’s simultaneous rise with the American industrial economy.

In startling contrast, “Marina’s Room,” 1987, by Tina Barney, is a present-day vision of parental indulgence and a lush display—amidst the sensual delight of those ribbons, those textures, that excess!—of wealth and love.

The chilling image by the great train photographer O. Winston Link’s “Living Room on the Tracks, Lithia, VA, December 16, 1958,” printed 1984, is a fitting companion to Barney’s intimate scene, and its polar opposite.

“Marina’s Room,” 1987, by Tina Barney

“Living Room on the Tracks, Lithia, VA, Debember 16, 1958,” by O. Winston Link

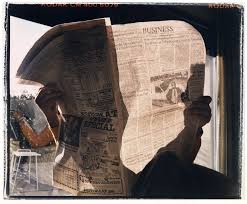

Imagination at Work yields “Portrait of my Father with Newspaper,” 1986, by Larry Sultan, part of an eight-year project documenting his parents’ lives. The project was spurred by his discovery of a box of home movies. I love this portrait, with its subtle insight into the relationship of son and father, as well as the suffused light emanating from the newspaper frame.

Lovers of photography, me included, never tire of Edward Weston’s sculptural images, such as “Pepper No. 30,” 1930. Teetering on the edge of a cliché but still not quite falling into Georgia O’Keefe skull territory, this image has all the mass

“Pepper #30,” 1930, by Edward Weston

and power of a Henry Moore Sculpture.

“Portrait of my Father with Newspaper,” 1986, by Larry Sultan

Teasing the photographic process into new realms, Ellen Carey’s “Dings and Shadows” series exposes photographic paper to light through colored filters. Next, the artist folds and crunches paper, exposing it to light from a color enlarger, then flattens it out again to be processed. The fascinating result is a new kind of painting using vivid color and texture.

“Dings and Shadows Series,” 2012, by Ellen Carey

Even though the show has closed, if your appetite needs further whetting, drag out your tablet and feast on the images at the Smithsonian’s American Art Gallery’s excellent website:

http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/online/photographs/exhibit/american_characters

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!