Art in the Round: The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Yesterday I took a fresh look at this vibrant museum on Washington’s National Mall. The third floor galleries have reopened after renovation, and, in celebration of the museum’s 40th anniversary, an installation—At the Hub of Things: New Views of the Collection—presents some sixty works in various media from the permanent collection.

Yesterday I took a fresh look at this vibrant museum on Washington’s National Mall. The third floor galleries have reopened after renovation, and, in celebration of the museum’s 40th anniversary, an installation—At the Hub of Things: New Views of the Collection—presents some sixty works in various media from the permanent collection.

Designed by Gordon Bunshaft—the architect also gave us the elegant Lever Building in New York City—the cylindrical building didn’t immediately wow the critics, or DC’s residents, for that matter:

Designed by Gordon Bunshaft—the architect also gave us the elegant Lever Building in New York City—the cylindrical building didn’t immediately wow the critics, or DC’s residents, for that matter:

“[The building] is known around Washington as the bunker or gas tank, lacking only gun emplacements or an Exxon sign… It totally lacks the essential factors of esthetic strength and provocative vitality that make genuine ‘brutalism’ a positive and rewarding style. This is born-dead, neo-penitentiary modern. Its mass is not so much aggressive or overpowering as merely leaden.” Ada Louise Huxtable, The New York Times, October 6, 1974.

“Cloud,” 2006, by Spencer Finch

I usually agree with Ada Louise Huxtable’s bracing criticism, but in this case, I’m inclined to side with The Washington Post’s Benjamin Forgey:

“[The Hirshhorn is] the biggest piece of abstract art in town-a huge, hollowed cylinder raised on four massive piers, in absolute command of its walled compound on the Mall…. The circular fountain…is a grand concoction…that for good reason has become the museum’s visual trademark.” Benjamin Forgey, The Washington Post, November 4, 1989.

“At the Hub of Things,” 1987, by Anish Kapoor

As you rise up the escalator to the third floor galleries you’re treated to Spencer Finch’s “Cloud (H2O),” 2006, a hovering galaxy of light fixtures and bulbs that manages to mimic a starry sky. Lovely to come back full circle through the outer galleries and admire it again.

The first object in this show that really grabbed me was Anish Kapoor’s “At the Hub of Things,” 1987, made of Prussian blue pigment and resin on foam. The wall notes tell us that Kapoor was inspired by the Hindu festival celebrating the blue-skinned goddess, Kali. Kapoor described this piece as “A hole in space…something that does not exist.” The work draws you in, as if into an Yves Klein blue-black hole. At first glance, the facing surface appears to be flat, but as you move around the conical object, you begin to see that it’s hollow.

“Canton Palace,” 1980, by Hiroshi Sugimoto

Nicely paired with “Hub” is Hiroshi Sugimoto’s “Canton Palace, Ohio,” 1980. To create this haunting photograph, Sugimoto opened his camera’s shutter at the beginning of a movie, and closed it at the end, thus creating this blinding void.

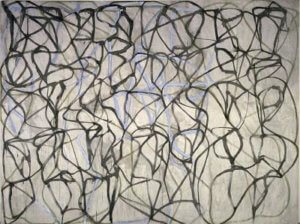

“Cold Mountain 2,” by Brice Marden

Minimalist Brice Marden’s huge, “Cold Mountain 2” was one of a series made between 1989 and 1991. This lively canvas writhes with energy and is a real eye-popper, despite the muted palette. We learn that in the 1980s Marden was drawn to the poetry of the Tang Dynasty hermit Hanshan (“cold mountain”) and was moved to explore calligraphy’s grand gesture and spontaneity.

“Sound Suit 2009, ‘Happy Easter,'” by Nick Cave

Far from Marden’s subtle approach, but equally engaging, is Nick Cave’s “Soundsuit, 2009, ‘Happy Easter.’” I was knocked out by this fanciful concoction of thrift store junk, beaded baskets and bangles, all topped by a papier-mâché Easter rabbit. It’s called a “soundsuit” because it clanks and tinkles when worn. I wanted to see and hear this dazzling Mardi Gras confection in motion. Voila! Click this YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=nick+cave+soundsuits

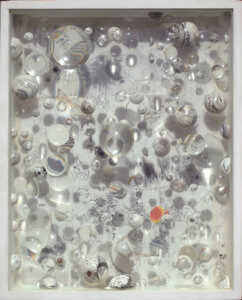

“Hommage a Jasper Johns,” 1964-65, by Mary Bauermeister

“In Memory of Your Feelings, or Hommage à Jasper Johns,” by Mary Bauermeister, 1964 – 65, hangs next to a work by Johns. In my view (pun intended) this mesmerizing piece is more in the spirit of Joseph Cornell than Johns. Made of glass lenses, wood, ink, and paint, this creation, whose title was adapted from a poem by Frank O’Hara—a great friend of artists—evokes psychedelic art of the day, trippy and mind-bending like seashells that balloon and morph behind the lenses.

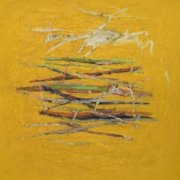

“Untitled No. 10,” 1980, by Paul Sarkisian

The tour-de-force “Untitled No. 10,” 1980, by Paul Sarkisian, in acrylic and silk screen on canvas, reflects several classic genres: trompe l’oeil painting, cubist collage, and mid-century abstraction, combining them in a new and confounding way. I defy you to stand before this one-dimensional painting and not feel compelled to slip your hand behind the diagonal row of colored paper, so convincing is its rendering. Your eye is equally fooled by the newspaper cunningly slipped inside the box fold. Well, your eye is fooled by the whole thing.

“Opposition,” 1968, by Gio Pomodoro

Giò Pomodoro’s “Opposition,” 1968, made of fiberglass and paint, blends the organic with the industrial in a surprisingly engaging way. The bulging and dimpled surfaces suggest human or aircraft skin on the point of bursting. It was only when I downloaded this image that I thought I saw a classically posed female form behind the surface.

One of the treats of this museum-in-the-round is that you have another show to look forward to: the inner round (with screened windows that look out into the courtyard and fountain) houses sculpture. As I usually enjoy paintings and works on paper more than sculpture, I didn’t think I’d want to tell you about the inner ring, but I took such pleasure in walking it, and was so struck by many of the works that I had to include a couple here.

“Indifferent One,” 1959, by Philippe Hiquily

I’m in love with Philippe Hiquily’s iron “Indifferent One,” 1959. Now we’re firmly back in the mid-20th century, a place I could dwell forever. How charming this piece is, and how technically difficult it must have been to balance the bulk of the body with those delicate pointy legs.

I had the same sense of home-coming with Reg Butler’s “Family Group,” 1948, also in iron, perhaps because it reminded me of my father’s family portrait, “The Three.” Come to my house and I’ll show it to you. For now, just enjoy this Saul Steinbergian family, so intertwined and interconnected, so quirky and strange, as all our families are.

“Family Group,” 1948, by Reg Butler

For those of us in Washington who love the museum, At the Hub of Things is not only a welcome coming-out party for the renovated third floor, but also a chance to see the collection in a new light. This selection from the permanent collection will not disappoint lovers of Andy Warhol, Louise Bourgeois, Sol Lewitt, and Bruce Nauman, to name a few, but it is not a show of the Hirshhorn’s greatest hits. Curators Evelyn Hankins and Melissa Ho present us with provocative choices and themes. Some of the work eludes me, of course, as I’m not always a fan of the contemporary conceptualist trope. Still, there’s much to soak up here, even if it doesn’t always hit the mark.

Joseph H. Hirshhorn

After making your way around both inner and outer rings, flop on the sofa in the Lerner room and take in the splendid view of the National Mall from its windows. The museum has a lively website as well, allowing you to search by artist and delve deeply into the vast collection bequeathed by newsboy turned financier and philanthropist, Joseph H. Hirshhorn. http://hirshhorn.si.edu/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!