Better than Picasso? Georges Braque and the Cubist Still Life, 1928-1945 at the Phillips Collection

“Plums, Pears, Nuts and a Knife,” 1926

I’ve always thought Picasso was over-rated, but never believed anyone agreed with me. After seeing this stunning show at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, I find that I’m not alone. Duncan Phillips, the founder of the Phillips Collection, felt that that Braque had advanced “the amazing innovations of Picasso.” Just so. In 1927 Phillips went on to say, “Braque is one of the few modernists who interests me and I must have a good example by him.” He paid $2,000 for “Plums, Pears, Nuts and a Knife,” 1926, the first Braque painting to be acquired by a U.S. museum.

Mariah Boone, the lead character in my novel, Still Life with Aftershocks, was heard to say, “Yes, a still life must be still, but it doesn’t have to be dead.” All throughout this show, I felt Mariah was looking over my shoulder enjoying the life pulsing from these works. Occasionally we high-fived each other when no one was looking.

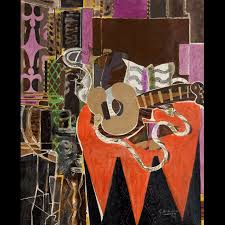

“The Round Table,” 1929

The show’s curator has assembled some 40 works from Braque’s “overlooked” mid-career and hung them in such a way that the viewer can see his evolution from the 1920s—“intimate and classical”—to the 1930s—“bold and ornamental—to the 1940s—“personal, daily life.” Many of these works are owned by the Phillips Collection and others have been drawn from varied institutions and private collections in the U.S and Europe.

“The Round Table,” 1929, is the first work in which Braque used sand, along with oil and charcoal, aiming for a tactile, layered effect. Among the many joys of this show are the profusion of quotes from Braque: “The guiding light of Cubism was the materialization of this new space which I could feel. So I began to paint mainly still lifes … another way of conveying the desire which I’ve always had to touch things.”

“Still Life with Grapes and Clarinet,” 1927

Purchased in 1929 as a mate to “Plums, Pears, Nuts and a Knife,” “Still Life with Grapes and Clarinet,” 1927, brings together, almost as a collage, the images that Braque continued to paint over and over for decades. In this way, the show reminded me of another superb one the Phillips mounted some years ago: Giorgio Morandi lovingly, meticulously, rendered the same objects in a seemingly infinite number of combinations, light, and perspectives.

“The Napkin Ring,” 1929

In the second room a table sitting among the paintings tells a fascinating story. “The Napkin Ring,” an inlaid marble floor panel, one of four, was based upon four paintings made in 1929 for the Paris apartment of Alexandre P. Rosenberg. When the Germans confiscated the building in 1940, it was converted into the “Institute for the study of Jewish Questions.” Somehow the floor panels survived. The Rosenberg family (the full story needs to be told) managed to retrieve them in 1949 and had them made into tables. Now, the original painted panels are at the Cleveland Museum of Art, gifts from the Rosenberg family. The craftsman who made the table received direction from Braque and managed to reproduce the floating knife, filmy table cloth, and vivid lemon in stone.

“Still Life on Red Table Cloth,” 1934

In the next room are paintings from Braque’s major exhibitions in Europe and the U.S. Carl Einstein, a friend and critic said of the 1933 Kunsthalle show in Basel, Switzerland, “Braque tirelessly varies the same motif and . . . heightens it . . . slowly and patiently he raises his aims.” You can see this process at work in “Still Life on Red Table Cloth,” (1934) and “Still Life with Guitar,” (1937 – 38). “The viewer retraces the same path as the artist,” Braque said, “and as it is the path that counts more than the thing, one is more interested by the journey.”

“Still Life with Guitar (Red Curtains),” 1937 – 38

At around this time he also said, “In painting, the contrast between textures plays as big a role as the contrast between colors,” and, “It is all the same to me whether a form represents different things to different people, or many things at the same time.” This statement seemed particularly apt in referring to “Glass with Fruit Dish,” 1931. Very abstract, this painting was inspired by Greek vase paintings that Braque saw in the Louvre. In it he carved thin lines in the black paint. “Objects do not exist for me except in so far as a rapport exists between them … it is the in- between that is the real subject of my pictures,” Braque said. Indeed, you can dwell in the in-between for hours in this show.

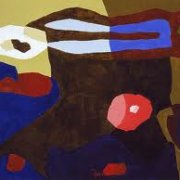

“Still Life with Pink Fish,” 1937

“Still Life with Pink Fish,” 1937, with its wonderful acid green, was shown in Braque’s first U.S. retrospective, along with “Le Gueridon,” 1935, a long panel featuring the same wild wallpaper as in “Pink Fish.” This striking motif appears again and again in subsequent paintings to marvelous effect.

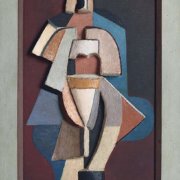

“Vase, Palette, and Mandolin,” 1936

At around “Vase, Palette, and Mandolin,” 1936, Braque’s epigrams on his art became hard to fathom and quite a lively discussion sprang up between several museum-goers, me, and the young staffer whose job it was to stand around and make sure no one touched any of those seductive surfaces. Braque said, “…the object is a dead thing. It comes to life when it is activated.” What did he mean by “activated”? Brought to life by the artist’s enlivening vision? Further on, he says, “A still life is no longer a still life when it is no longer within arm’s reach.” One woman exclaimed, “That makes no sense at all!” We grappled with its meaning but didn’t have much success. It was a little like a Bob Dylan lyric which you intuit to be true, even if you couldn’t possibly say why.

“Mandolin and Score (The Banjo),” 1941

“Mandolin and Score (The Banjo), 1941, is a knockout with its graphic persimmon tablecloth and wildly undulating banjo strap. “Studio with Black Vase,” 1938, is familiar from visits to Washington’s Kreeger Museum. This is the first appearance of a skull in Braque’s work, but he doesn’t use the skull as a reminder of human mortality as others have done. For him, “A skull is a beautiful structure and it is used to waiting.” Perfect subject matter for a maker of still life.

“Wash Stand before the Window,” 1942

“Wash Stand before the Window,” 1942, frames the open sky in a way that was eerily familiar. What did it remind me of? Suddenly it came to me, and after soaking up as much of Braque as I could for one visit, I went downstairs to find Pierre Bonnard’s “The Open Window,” 1921, one of my favorite paintings. Could Braque have seen it? One can only speculate and feel fortunate to be able to see both of them in this jewel of a gallery.

“The Open Window,” by Pierre Bonnard, 1921

The show, which was organized with the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St. Louis, will be on view until September 1, 2013.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!