“Wapping,” 1860 – 64

Each of the Smithsonian museums has a character of its own, but they all have one thing in common: that feeling of safety and calm, the way a sacred space must feel to the religious. At the Arthur M. Sackler Asian Art Gallery you descend below-ground to the gallery space, leaving the world behind, sinking into yourself, as you enter a new, sandalwood-smelling, realm.

“An American in London: Whistler and the Thames,” running now until August 17, 2014, is magical. The show gives us glimpses of James McNeill Whistler’s mid-nineteenth century London in all its gritty, booming tumult along an increasingly industrialized river. One of my favorite painters, I’d see any show of Whistler’s work, anywhere, any time. Here, as you walk from dusky room to dusky room, the painter’s evolution unfolds, with his earlier realistic images giving way to more and more impressionistic ones, as if the London fog is stealing into the gallery itself.

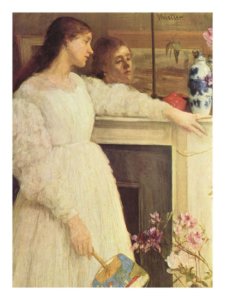

“Symphony in White, No. 2, The Little White Girl,” 1864

“Wapping,” 1860-64, depicts Whistler’s Irish mistress, Joanna Hiffernan, enjoying the company of a sailor and another man. Originally painted as a prostitute, the model is, after four years of reworking, an ambiguous, contemplative figure. The view from the porch of The Angel, a public house near Whistler’s own Chelsea rooms, gives out on the bustling wharf. Painted with painstaking detail, the realistic image makes you feel as if you’ve just arrived, joining the group to have a pint. All the painting-over seems to have muddled Joanna’s image a bit, as if her head is bathed in, or merging with, the light coming off the river.

In “Symphony in White, No. 2: the Little White Girl,” 1864, we see Joanna again, wistfully posed in Whistler’s porcelain and azalea-filled dining room. She holds a fan decorated with an image by Utagawa Hiroshige, one of the famous views of Edo (now Tokyo). Next to the painting is the woodblock fan print itself, “The Banks of the Sumida River,” 1857. The wall placard tells us this view is from the middle of the Azuma Bridge, a similar positioning to Whistler’s paintings of London’s distant Crenmore Gardens, with its nightlife, cafes, and fireworks.

“The Banks of the Sumida River,” by Utagawa Hiroshige

“Japonisme,” all the rage in France and Europe, was to have a profound effect on Whistler, who owned an extensive collection of Japanese woodblock prints, and who sought to incorporate characteristic Japanese compositional elements into his work. He enjoyed posing European models in “oriental” costume, as he does here in “Caprice in Purple and Gold: the Golden Screen,” 1864. Here Joanna is dressed as a Japanese courtesan, sorting through an array of woodblock prints. Hiroshige and Hokusai were “…the filter through which Whistler later re-envisioned the industrial views of London out his window.”

“Caprice in Purple and Gold: the Golden Screen,” 1864

“Chelsea in Ice,” is the view from Whistler’s bedroom on one particularly cold February day in 1864. His famous mother, staying with him at the time, said she nearly froze to death as he painted, in a frenzy, with the window wide open. The slabs of ice are suggested by broad, flat brush-strokes, in his new gestural, almost abstract style.

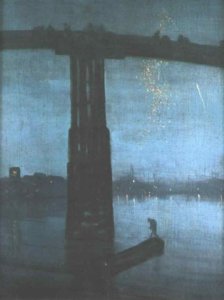

The link between Japanese prints and “Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge,” 1872-73, can be seen by comparing Whistler’s painting with Hiroshige’s “Bamboo Yards, Kyobashi Bridge,” 1857.

“Chelsea In Ice,” 1864

This painting—of Old Battersea Bridge—was the one I’d come to this exhibition to see. On loan from the Tate, London, this incandescent painting, draws the viewer in, the spray of fireworks overhead like something otherworldly. It’s encased in a gorgeous gold and turquoise frame that looks like it was cut from the wall of the famous “Peacock Room,” designed by Whistler for his patron, the shipbuilder Frederick R. Leyland, now reconstructed in the neighboring Freer Museum. The very informative accompanying notes tell us that Whistler first calls these ephemeral night visions “moonlights,” until Leyland suggested the term “nocturne.” Whistler defined the nocturne as a work valuable as art only, without any “…outside anecdotal interest.”

“Bamboo Yards, Kyobashi Bridge,” by Utagawa Hiroshige

We can see what he was getting at here, a suggestive impression of urban night, but the prevailing Victorian sensibility was not prepared to follow where Whistler was leading. Indeed, the critic John Ruskin gave the Old Battersea Bridge painting such a scathingly bad review that Whistler sued him for libel in 1878. And won. Not that it made much difference to the public, whose tastes still ran to realistic, often moralizing pictures. Whistler’s style was so radical—with its almost monochrome palette, low perspective and murky aspect—that many had trouble making out what the picture represented.

From our perspective, the painting is itself a bridge, connecting the Victorian age to the age of modernism.

“Nocturne in Blue and Gold–Old Battersea Bridge,” 1872-73

In Whistler’s words, he wanted to paint the point at which “…the evening mist clothes the riverside with poetry, as with a veil, and the poor buildings lose themselves in the dim sky, and the tall chimneys become campanili, and the warehouses are palaces in the night…Nature…sings her exquisite song to the artist alone, her son and her master—her son in that he loves her, her master in that he knows her.”

See more at http://www.si.edu/Exhibitions/Details/An-American-in-London-Whistler-and-the-Thames-5141

“The Peacock Room,” 1908

Also, “The Peacock Room Comes to America”

http://www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/current/peacockRoom/pano.asp

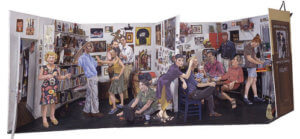

Star of the show may well be “Loft on 26th Street,” by pop art trickster Red Grooms (plywood, cardboard, paper and wire), 1966-7. This delightful piece shows us the studio apartment of Mimi and Red Grooms, “Home of Ruckus Films,” and its denizens partying up a storm. Grooms himself is slicing potatoes at the right of the diorama. Endless wonderful things to look at here: the art lining the walls, the detailed clothing, the contents of the fridge, even a recognizable china pattern my friend Pat had when we were living in New York’s lower East Side.

Star of the show may well be “Loft on 26th Street,” by pop art trickster Red Grooms (plywood, cardboard, paper and wire), 1966-7. This delightful piece shows us the studio apartment of Mimi and Red Grooms, “Home of Ruckus Films,” and its denizens partying up a storm. Grooms himself is slicing potatoes at the right of the diorama. Endless wonderful things to look at here: the art lining the walls, the detailed clothing, the contents of the fridge, even a recognizable china pattern my friend Pat had when we were living in New York’s lower East Side.

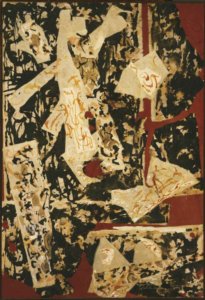

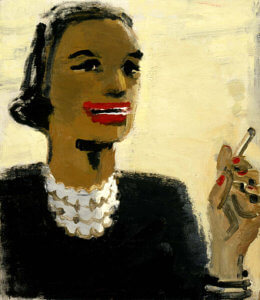

Fraught with psychological overtones, the image led Burgess to make this new dance expressing “an emotional terrain of the mind” whose predominant theme is the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which feelings are unresolved.

Fraught with psychological overtones, the image led Burgess to make this new dance expressing “an emotional terrain of the mind” whose predominant theme is the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which feelings are unresolved. In this piece, Burgess’s characteristic spare, clean lines are punctuated with sharp, pecking arm and hand gestures, and an idiosyncratic pulling motion that seems to draw an invisible thread from inert figures on the floor. Fluid, organic movements mingle and merge in hypnotic ways, the dancer’s faces showing more and more eye contact and emotion—ranging from wariness to openness to outright fear—as the dance progresses. This churning intensity propels the dancers upward into spectacular lifts and downward into curled resting positions. Twice, male dancers lift women and hold them aloft, straight as exclamation points, like “pillars of emotion,” to use Burgess’ words.

In this piece, Burgess’s characteristic spare, clean lines are punctuated with sharp, pecking arm and hand gestures, and an idiosyncratic pulling motion that seems to draw an invisible thread from inert figures on the floor. Fluid, organic movements mingle and merge in hypnotic ways, the dancer’s faces showing more and more eye contact and emotion—ranging from wariness to openness to outright fear—as the dance progresses. This churning intensity propels the dancers upward into spectacular lifts and downward into curled resting positions. Twice, male dancers lift women and hold them aloft, straight as exclamation points, like “pillars of emotion,” to use Burgess’ words. While exploring the uncertainty of short relationships that “are not love, not trusting,” the dance shows us the various effects of touch—it can soothe and it can hurt. Hands caress, appear to strike, swoop in crane-like arches, and, in staccato bursts, express frustration and tension between partners. Dancers also leaned their heads on their partner’s shoulders, backs, and arms, allowing momentary respite from the mood of suspended anxiety and bringing a fleeting sweetness into the mix. Not that this sustained emotion is hard to watch. Quite the contrary. It would have been impossible to look away.

While exploring the uncertainty of short relationships that “are not love, not trusting,” the dance shows us the various effects of touch—it can soothe and it can hurt. Hands caress, appear to strike, swoop in crane-like arches, and, in staccato bursts, express frustration and tension between partners. Dancers also leaned their heads on their partner’s shoulders, backs, and arms, allowing momentary respite from the mood of suspended anxiety and bringing a fleeting sweetness into the mix. Not that this sustained emotion is hard to watch. Quite the contrary. It would have been impossible to look away. The complex choreography, seemingly propelled by the swirling, eddying music, conjures bodies of water meeting, joining and flowing in sometimes gentle and sometimes turbulent ways. I was particularly struck by the complex whorl of movement in which the woman lifted the man, and another pairing in which the woman rolls her head and upper body along the outstretched arm of the man. The work is filled with many such strikingly original moments.

The complex choreography, seemingly propelled by the swirling, eddying music, conjures bodies of water meeting, joining and flowing in sometimes gentle and sometimes turbulent ways. I was particularly struck by the complex whorl of movement in which the woman lifted the man, and another pairing in which the woman rolls her head and upper body along the outstretched arm of the man. The work is filled with many such strikingly original moments. “Confluence” ends with a woman placing her hand on a fallen man’s body. Her expression is unreadable—does she feel victorious, dominant, or tender? It’s a moving end to a piece in which the viewer is pulled into a darkly absorbing psychological space. Doris Humphrey would have loved it!

“Confluence” ends with a woman placing her hand on a fallen man’s body. Her expression is unreadable—does she feel victorious, dominant, or tender? It’s a moving end to a piece in which the viewer is pulled into a darkly absorbing psychological space. Doris Humphrey would have loved it! And, if you haven’t seen it yet, “Dancing the Dream” is on view in the National Portrait Gallery until July 13, 2014.

And, if you haven’t seen it yet, “Dancing the Dream” is on view in the National Portrait Gallery until July 13, 2014.