Dots Fine—Neo-Impressionism and the Dream of Realities: Painting, Poetry, and Music

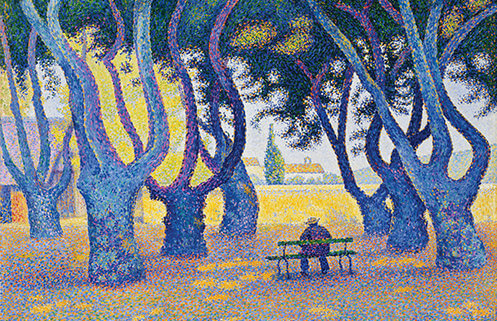

“Beach at Vignasse,” by Henri-Edmond Cross

Sorry about the pun. I just had to poke a little fun at the high-blown title of this show, now on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC.

The exhibition includes some 70 works by 15 artists working in the late 1880s to mid-1890s– the period after Impressionism and before Cubism. The visiting curator, Cornelia Homburg, makes the case for Neo-Impressionism—or pointillism, as I have always thought of it—as more than an optical experiment with light and tiny strokes of color, but as a response to the dreamy expression of Symbolist writers and musicians. Rather than depicting a singular event in a particular place, the Neo-Impressionist impulse was to distill an experience, create a dream, and pull the viewer into a universal vision.

“Adagio, Setting Sun, Sardine Fishing, Opus 221,” by Paul Signac

I happened to be in the galleries when the curator was escorting a group of VIPs on a private tour. I eavesdropped a bit, but wanted to see the works without the lens of even her learned eye. So I can’t give you insider goodies, but what I can tell you is that she was positively rapturous about the paintings. I found them rather chilly, empty, and technical. But I loved watching Ms. Homburg’s sweeping arm gestures and hearing her little audience laugh with her. So maybe there’s more here than met my eye. For this review, I’ll focus on the paintings that drew me most.

“Beach at Vignasse,” 1891-92, by Henri-Edmond Cross, appears to be a contradiction of the stated premise. Here, the artist seems to be in love with a specific place, its plant life and gentle light. In the distance, the sea shimmers—you can almost feel the heat on your skin, smell the fragrant sage and delicate flowers.

“L’Ile La Croix, Roen (the Effect of Fog), by Camille Pissarro

Paul Signac’s “Adagio, Setting Sun, Sardine Fishing, Opus 22,” 1891, on the other hand, gives us sardine fishing reduced to its most pure expression. No smelly fish to spoil the rapture—not even any people. Many of the canvasses in this show are empty of human life. This was the intent, as I gleaned from a scrap of Ms. Homburg’s overheard talk. I find it difficult to connect the “adagio” and “opus” of the title with any evocation of music in this work. Perhaps the boats are meant to signify musical notes, but instead the image reads as—however scintillating the surface color—static.

“”The Beach at Blankenberghe,” by Henry van de Velde

In the room entitled “Urban Landscapes,” Camille Pissarro’s “L’Ile LaCroix, Roen (the Effect of Fog),” 1888, portrays the newly important river in industrialized European cities. Many Neo-Impressionists were anarchists, painfully aware of the desperate conditions of the poor, yet the paintings here focus on atmospherics rather than human suffering.

In the summer, the accompanying notes tell us, many painters went to the country or the coastlines of Belgium or Northern France. Much of the work they did in pastoral settings was sketched out of doors and then finished in the studio. Perhaps this is why much of the work feels contrived, even stiff.

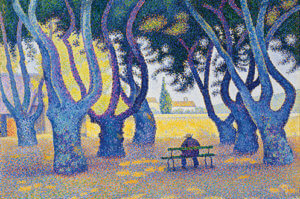

“Place des Lices, Saint-Tropez, Opus 242,” by Paul Signac

“The Beach at Blankenberghe,” 1889, by Henry van de Velde exemplifies the “absence and ambiguity” of these works. One experiences the scene (and several others) as ominous, freighted with some free-floating angst, much like the mood of isolation and loneliness in the word of Edward Hopper. Yet Hopper was drawn to people with their very particular inner despair or ennui. Here, the tiny people are insignificant gestures in the enormous empty space.

In the room called “Arabesque” we learn that these painters were attempting to create “a more long-lasting idea of reality” (emphasis mine) rather than recording fleeting events. This urge to synthesize seems to have backfired. The paintings are so stylized, despite their surface beauty, that they become mere illustrations rather than works with great depth and power.

“Place des Lices, Saint-Tropez, Opus 242”, 1893, by Paul Signac is one of the more appealing paintings in this group, with its undulating trees and rich color. Yet the lone man is almost cartoonish, sitting under the trees on yet another solitary bench.

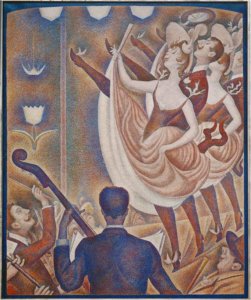

“Le Chahut,” by Georges Seurat

The room titled, “Poetry, Music and the Synergy of the Senses,” attempts to show us the connection between painting and music for the Neo-Impressionists—unconvincingly, in my view. We learn that Theo van Rysselberghe illustrated the poet Emile Verhaeren’s works, that Maximilien Luce and Paul Signac designed covers for Symbolist composer Gabriel Fabres, and that painters reviewed new music and written works and vice versa. This is interesting, but the paintings in the room are imbued with the same stilted, thoroughly non-musical flatness as many of the other pieces. The collaboration between the arts only went so far—especially when we think of the astonishing meeting of art, dance, design, and music that Sergei Diaghilev achieved not very much later.

In Frenchman Georges Seurat’s study for “Le Chahut,” 1889, the dancers, although still decorative, are indeed engaged in a wild and spirited dance. We see more dynamism in the composition as well, with its angled stage and flanking musicians.

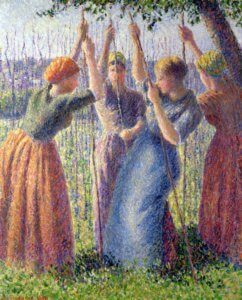

In the room called “Timelessness” we are told that the Neo-Impressionists had a “special affinity with rural life and the peasant.” Camille Pissarro’s “Peasant Women Planting Poles the Ground,” 1891, ripples with color, but again gives us idealized women symbolizing toil in the fields, but conveying little of the muscle and heat of the task at hand.

“Peasant Women Planting Poles in the Ground,” by Camille Pissarro

In the final room, “Arcadia,” Henri-Edmond Cross’s “Beach at Cabasson (Baigne-Cul),” 1891-2, is a standout. Unfortunately, an image of this lovely work (on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago), is not available. Go to see it, and the rest of these works, if only to better understand a sometimes overlooked moment in art history. The show is up until January 11, 2015.

http://www.phillipscollection.org/events/2014-09-27-exhibition-neo-impressionism-dream-of-realities

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!