More Than Just a “Scream” – Edvard Munch: 150th Anniversary Tribute, National Gallery of Art

“The Sick Child”

The National Gallery of Art is many things to those of us lucky to live in or around Washington, DC: a place to soothe the soul, delight the senses, and feed the mind. Last Wednesday my friend Karen alerted me to a gallery talk by David Gariff, a renowned Munch art historian—part of the 150th Anniversary Tribute to Edvard Munch, Norway’s most well-known visual artist.

Gariff, who is as much a showman as scholar, opened the talk standing just outside the small gallery where a trove of twenty Munch prints was being shown. Gariff unequivocally places Munch in the Expressionist camp, with his very personal, emotional approach to painting and printmaking. A “seminal, transitional” figure between Van Gogh and the German Expressionists, Munch’s output was purely autobiographical: “I don’t paint what I see, I paint what I suffer.” And suffer, he did. He left behind some 300 journals (now at the National Gallery of Art in Oslo) chronicling the events and emotional upheavals of his life. As a child, tuberculosis stalked his family. Both his mother and elder sister, Sophie, succumbed. A brother, Peter, died of pneumonia. Munch himself contracted the disease, but survived.

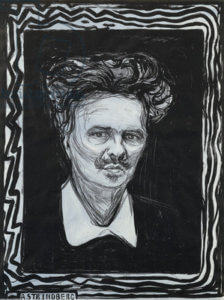

Portrait, August Strindberg

Inside the gallery, we stop at “The Sick Child,” 1886, print based upon his “breakthrough” painting. (Most of the images seen here were variations on paintings.) As a young man, Munch studied at the Academy at Christiania, and produced conventional student work. In Paris, he painted like Pissarro and Monet—outdoor, sun-washed images. Searching for a way to express his inner life, he abandoned much of what he’d learned in Paris and employed “kinetic, brutal” methods: slathering and scraping the paint. The tortured space around the face of the dying Sophie makes her appear to be “disintegrating,” as indeed she was.

In the 1896 portrait, August Strindberg’s head, so full of ideas and volatile emotions, seems to mushroom up and out. In Berlin, Munch had been caught up in the intellectual circle of the “Nihilistic, misogynistic, and darkly Freudian,” Strindberg.

“The Vampire”

Next we see “The Vampire,” 1894. Originally, Munch called the image “Love and Pain,” and it embodies all the femmes fatales that Strindberg could have cooked up: Lilith, Delilah, Salome…and a redhead to boot, calling to mind Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s (see my blog post, “Hair!” Pre-Raphealites invade Washington”) women with ensnaring hair.

“Girl with Heart”

In “Girl with the Heart,” 1899, things get even darker. Our gal is eating the heart. Gariff tells us that women at this time (1898 – 99) are gaining power—the vote, property ownership, independence from men. In Ibsen’s “The Doll’s House,” the heroine takes her ring off and flings it at her despicable husband. Women’s power is for Munch a notion both frightening and thrilling.

“Madonna”

“Madonna” shows us a seductive red-haloed woman, calling up images of jealous rages rather than saintly piety. Gariff points out the “ectoplasmic” background out of which our temptress emerges, like amniotic fluid. Munch, he says, would have been aware both of the genuine advances in science at the time, but also of the pseudo-science of auras. The Madonna’s radiating power—that of creating life itself—threatens to overwhelm. Spermatozoa swim around the frame while a huddling “homunculus” of a fetus crouches in the corner.

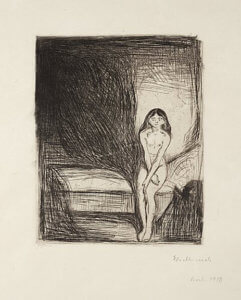

“The Young Model”

A tender sensibility regarding the female, by contrast, can be seen in “The Young Model,” 1894, depicting the moment a young girl experiences her first menstrual period. The girl’s body hunches forward with a “deer in the headlights” look on her face while a “scary shadow” looms across her—a decidedly non-erotic pose. This piece, as a painting, I believe, was exhibited at Munch’s first showing in Berlin, and as the subject matter of this and other works was considered “incendiary,” the show closed in two days.

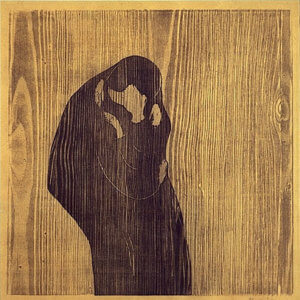

“A Kiss”

In “A Kiss,” 1898, the entire world fades away as the couple merges and floats before the sweep of the wood grain. Munch, we learn, was a great admirer of Gauguin, particularly his woodcuts. Here we see Munch’s notion of an all-enveloping love, ultimately resulting in total loss of identity. Gariff observed that this was a late version in which all “clap trap” of daily life (the room, furniture, etc.) had been eliminated. Even the figures’ eyes, mouths, and faces are gone; the abbreviated hands are “flippers,” and the merging figures become one big “phallic” shape.

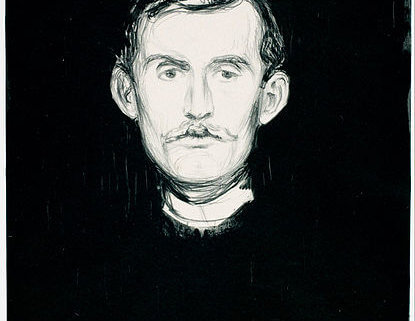

“Self Portrait”

By his “Self Portrait, 1895, Munch was well on his way to being an alcoholic, agoraphobic, paranoid with auditory hallucinations. Munch’s haunted face floats eerily against a black background. The whole, Gariff pointed out, looks like a funerary stele, with Munch’s name spelled out along the top and the skeleton arm across the bottom of the image. By 1904 his mental state had deteriorated to such a point that Munch spent eight months in a Copenhagen clinic detoxing from his alcohol abuse and being treated for his mental illness. After eight months he came out a changed man.

“The Scream”

“The Scream,” 1895, a pastel version of which recently sold at Sotheby’s (in 12 minutes for $119 million) shows us a real place and time rather than a purely abstract depiction of extreme anxiety. In his diaries of 1893 Munch recounts being out walking with friends at sunset, and he, paralyzed with fear, “… felt a loud unending scream pierce nature.” Gariff speculated that this fugue state might have had to do with the road being close to both the slaughterhouse and the insane asylum where Munch may have visited his sister. The screams of the dying animals and the insane could well be heard from this vantage point. The face of the screamer is very like the “homunculus” seen in the frame of “Madonna.” Gariff, in a fascinating aside, showed a photograph of a mummy—made famous by a photograph by Brassai—that was in the Trocadero Museum in Paris (now the Museum of Man). Munch which surely would have seen this haunting skeletal face and it pops up again and again in his work.

“The Brooch (Eva Mudocci)”

The final image, “The Brooch” (Eva Mudocci), 1903, shows us a lovely woman surrounded by more swirling hair. Munch said the brooch was, “The stone that fell from my heart.” Most art historians had come to the conclusion that Munch, destroyed by earlier affairs (he never married), did not enter into a love affair with Eva. Now comes Janet Weber, a nun, who quietly claims to be one of two children Eva had with Munch. Eva never told him of the children. Janet Weber says she, potentially his sole direct heir, doesn’t want money. There has been no test as yet, but some distant relatives of Munch are still alive and could provide DNA samples. Stay tuned…

Janet Weber

The show closed July 28, yesterday, so all those wonderful prints are back, or on their way back, minus their frames, to the drawers in the gallery archives. Seeing them was a rate treat.

Wait! There’s more! David Gariff will give two lectures: “The Art of Edvard Munch: Early Work,” on August 18 at 2:00pm, and “The Art of Edvard Munch: Late Work,” August 25 at 2:00pm, both in the East Building Concourse Auditorium. They promise to be rich with Munch lore, biography, and insights into this fascinating artist.

Munch had good taste. He seemed to like redheads.

Or be terrified of them!