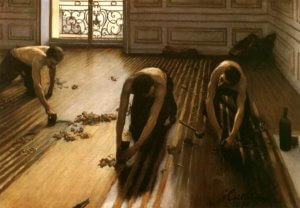

“The Floor Scrapers,” 1875

Gustave Caillebotte? The name doesn’t spring to mind if you’re asked to rattle off a few well-known Impressionist artists. Yet he was a master of all they sought to do—to paint light, employ unusual perspectives, and render life as it exists—raw, direct, unidealized. Discover him for yourself at a wonderful show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC: Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye.

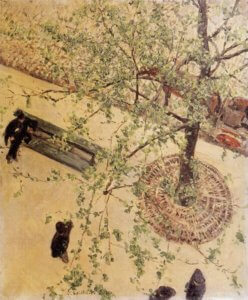

“Rue Halevy, Seen from the Sixth Floor,” 1878

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Caillebotte was not a starving artist. Far from it—he was an independently wealthy young Parisian, having inherited his family’s fortune (made in military textiles) at twenty-six. His wealth was one reason his paintings are not more well-known. He simply didn’t need to sell them and they remained in private hands until the mid-twentieth century when they began to trickle out into the market.

“Boulevard Seen From Above,” 1880

In 1873 Caillebotte put aside a career in law and engineering and enrolled in the Ecole des Beaux Arts. At about the same time he began hanging out with the likes of Edgar Degas, Pierre-August Renoir, and Claude Monet.

Encouraged by these artists’ admiration of his work, he entered “The Floor Scrapers,” 1875, in the Paris Salon show of the same year. It was thumpingly rejected, termed “vulgar”—and worse. Established taste-makers of the day decreed that if you painted the lower classes at all, you must show them as idealized peasants, not half-nude laborers. To hell with them! I love this painting. The figures strike me as very like Degas’ dancers, not so much in the style (the Caillebotte piece is more realistic, less fuzzy around the edges), but in the way the artist conveys his love of form, his love of the physics of the action. The light falls gently on the stripped floor as the workers bend to their task, likely in the room that was to become Caillebotte’s studio. The figure on the right turns his head slightly to say something to the one in the middle, while the figure on the far left, reaches his arm into the composition, leading the eye naturally to the foreground and back to the elegantly figured window. Note the bottle of wine on the hearth waiting for a break or lunch.

“Paris Street, Rainy Day,” 1877

“The Rue Halevy Seen from the Sixth Floor,” 1878, gives us a view of Caillebotte’s modern city: his building is to the right, the Opera just beyond it. The sweeping changes to the old medieval Paris made by Baron von Haussmann—the geometric layout, widened boulevards, open parks, and uniform building façades—created a splendid panorama for Caillebotte’s eye. I love the scrap of light at the horizon, and feel I’ve seen that very sky in Paris. The most dramatic use of skewed perspective, is evident in “Boulevard Seen from Above,” 1880. We picture the artist hanging out the window precariously to capture this image of foreshortened flaneurs along the boulevard, the lacy branches of the tree contrasting nicely with the straight planes of the street and bench.

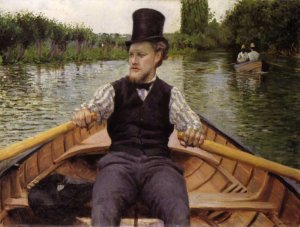

“Portrait of Paul Hugot,” 1878

My guess is that you, like me, do know the most famous painting Caillebotte made, for it now hangs in the Chicago Art Institute and has been reproduced on an infinite number of umbrellas, tote bags, scarves, and mouse pads. Yep, you guessed it—the iconic “Paris Street, Rainy Day,” painted in 1877 when the artist was just twenty-nine. This tour de force canvas (the largest he ever painted) gives us a-caught-in-the-moment view of the broad boulevard and its stylish denizens. The effect of the muted palette, looming scale and carefully choreographed action give the piece a static monumentality, even as it shows us the anonymity and alienation of the hurrying figures. The green street light bisects the picture, creating two dioramas with their own integrity. The flat iron building is a portentous presence, as if about to surge forward into the painting. The couple seems not so much individuals, but nineteenth century avatars—the personification of a chic Parisian couple, and, while together, each seems isolated from the other. The effect is not unlike the vaguely unsettling atmosphere of an Edward Hopper painting.

“A Man at his Bath,” 1884

Many of the portraits in this show were painted for friends and relatives and then given to the sitters—another reason they remained in private hands so long. The “Portrait of Paul Hugot,” 1878, is particularly charming. This dandyish young man, cut loose from his moorings—no interior, furniture, or rugs, ground him—appears to float in the steam of the trains at the Gare St. Lazare. It must have been a very radical portrait in its day.

Another view of the radical, courageous side of this artist’s vision is “A Man at His Bath,” 1884. Utterly unglamorous, this fellow towels off vigorously, his clothes in a pile by his side. The choice of a male subject, not heroized or idealized, scandalized audiences of the day.

“A Boating Party,” 1877-78

One gallery is devoted to loosely painted outdoor pictures made in Yerres, 15 miles south of Paris. Here in his family’s summer home along the Yerres River, Caillebotte likely took up painting and drawing as a boy. We don’t know who the young man is in “A Boating Party,” 1977-78, but clearly he’s a Parisian on holiday, dressed in his formal clothes. His expression of mild discomfort, looking off to one side, may belie his unease on the water, while the more appropriately dressed boaters in the distance placidly drift down river in their curious boating caps. Once again, I get the flash of Hopper—the solitary figure, the sense of alienation.

“Pastry Cakes,” 1881

Leaving the placid Yerres River, we enter a food hall—a small gallery filled with all manner of foodstuffs: a cut of beef, glistening lobsters, hanging hares, a calf’s head and ox tongue, game birds, and jewel-like fruits, glamorously displayed. My favorite—a precursor to Wayne Thibaud—“Pastry Cakes,” 1881.

” Dahlias, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers,” 1893

Also in 1881, Caillebotte moved to a country home at Petite Gennevilliers, leaving the art scene behind, and devoted himself to racing sail boats and gardening. He never married, but left a substantial bequest to a woman presumed to be his long-time mistress. His love of gardening is apparent in “Dahlias, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers,” 1893. The magnificent flowers are given top billing in the foreground, with a wisp of a woman (his mistress?) pausing as if to check her cell phone on the path.

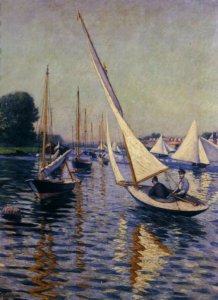

“Regatta at Argenteuil,” 1893

Touchingly sad is “Regatta at Argenteuil,” 1893, a self-portrait, with the artist looking wistfully out at the distance, his sailing partner turned away, as if the artist somehow intuited that he was not long for this world. Caillebotte was to die suddenly from a stroke while gardening only a year later, at 45.

In addition to his artistic contribution, Caillebotte was a patron of the arts, generously keeping many of his colleagues’ careers afloat. His extensive collection included Degas, Monet, and Renoir, among others, and upon his death, it became the corner stone of France’s national Impressionist collection.

This engaging show, with its many facets and surprises, reveals Caillebotte’s substantial role in the Impressionist movement and his influence on modern art to come.

Organized by the National Gallery of Art and the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye will be up through October 4, 2015. http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/exhibitions/2015/gustave-caillebotte.html