Winging it at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

“Zugunruhe,” 2009, by Rachel Berwick

The exhibit, “The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art,” now at the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum, marks two anniversaries: the 1914 extinction of the passenger pigeon and the establishment of the Wilderness Act in 1964.

If you, like me, find birds fascinating, but can never get them to sit still long enough to get a good look at them, then this is the show for you. An 1840 quote from Audubon opens the show: “When an individual [bird] is seen gliding through the woods and close to the observer, it passes like a thought and, on trying to see it again, the eye searches in vain; the bird is gone.”

Detail, “Zugunruhe”

As you enter this sharply focused small show, you’re confronted by a glassed-in tree filled with glimmering rust-colored birds. As you walk around the piece, the birds appear (reflected in two-way mirrors) to preen and peck. The tree is lifelike; its leafless branches are covered with lichen and its trunk rooted in moss, but the birds—made of polyester resin—are amber relics of long-extinct passenger pigeons. The effect is eerie. The title of the piece, “Zugunruhe,” made in 2009 by Rachel Berwick, refers to the “night time restlessness birds exhibit before migration.”

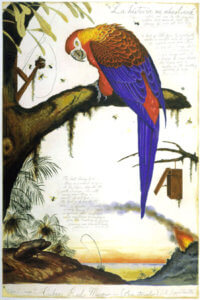

“La Historia Me Absolvera,” 1999, by Walton Ford

Part of his series of colored etchings, “Fables for Tomorrow,” “La Historia Me Absolvera,” by Walton Ford, 1999, gives us the brilliant glory of the now extinct Cuban Red Macaw. Approaching this large magnificently colored work, you’re sure it’s a long-lost Audubon, so closely does it mimic the great naturalist’s style. But no—Ford was born in 1960. The accompanying notes tell us that the artist slipped a political message into the beak of the macaw, and, meant to symbolize Cuban leader Fidel Castro, the bird does have a crafty glint in his eye. The legend—“History will absolve me,” is taken from Castro’s 1953 speech before an attack on an Army barracks. Given the recent opening of diplomatic relations with Cuba, one can’t help but think that we’re one step further to that old bird’s extinction.

“The Dodo Museum,” 1980, by David Beck

In the same vein, but without the political twist, is “The Dodo Museum,” 1980, by David Beck. Inside this charmingly detailed structure we see a skeleton—a la the Museum of Natural History’s dinosaur bones—of the extinct dodo.

“Biodiversity Reclamation Suit: Passenger Pigeon,” 2008, by Laurel Roth Hope

Extending this theme is Laurel Roth Hope’s series (2008-2012), “Biodiversity Reclamation Suits for Urban Pigeons.” The artist has crocheted detailed “suits” for current day pigeons to wear, here modeled by carved wooden pigeon mannequins on walnut stands. Before embarking on her art career, Hope worked as a park ranger and conservator and her abiding love of nature shines through in these adorable creations. But as the curator’s notes say, these works force us, “…despite the humor and charm, to face the futility of recovering lost biodiversity.”

“Penetrators (Large),” 2012, by Fred Tomaselli

“Penetrators (Large),” 2012 by Fred Tomaselli (photo collage, acrylic, and resin on wood) shows another sort of threat to a lone, defenseless bird. This absorbing work draws us in to its writhing snakes within the snake, an almost 3-D effect created by layers of resin covering photo montage. The swirling psychedelics sparkle against deep black background, reminding us that Tomaselli was said to have embedded hallucinogens into his work: pills and cannabis among them, but now he says, that’s all behind him. This stunning apparition demonstrates his on-going fascination with alternate reality and visionary encounters with nature, however he may find them.

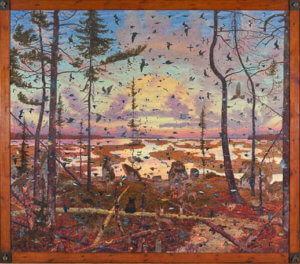

“Nin Mamakadendam,” 2011-2012, by Tom Uttrech

Tom Uttech’s 2011-12 “Nin Mamakadendam,” (oil on linen), is still another panoramic vision of teeming wildlife. This Wisconsin artist painted the hundreds of recognizable bird species—in full migratory flight—from memory. Meticulously detailed, this piece (and several others by Uttech) gives the viewer a heightened vision of nature, with the little bear at the still center, watching it all. Some sprightly foxes and other small animals are visible in the underbrush. Viewing this piece with all its rushing momentum, we hearken back to the tree full of resin pigeons and their “restlessness before flight.”

“”Untitled #1180 (Beatrice),” 2003-2008, by Petah Coyne

The mystery and fearsomeness of nature come to the fore in “Untitled #1180 (Beatrice), 2003-2008, by Petah Coyne. This ominous mixed media sculpture is said to represent Beatrice, “A woman draped in black and purple.” As Dante’s escort to heaven, Beatrice can also be seen as a “mediator between humanity and the spiritual world.” Hmmmm. I don’t see it. I walked all around this towering piece and could not see the figure of a woman, unless the artist is representing the female as an all-devouring force of destruction. I more closely identified with the poor taxidermied ducks going belly-up in the maelstrom of what appears to be lava mixed with funereal black flowers, driftwood, and pearl-headed hatpins. Shudder.

Detail, “Untitled #1180 (Beatrice)”

As you’ve gathered, “The Singing and the Silence” gives us depictions of our feathered friends in many guises, from those that raise Alfred Hickcockian hackles, to the idyllic pastoral vision of Walden Pond. Come and see for yourself—no binoculars required.

The show is up until February 22, 2015.

http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/archive/2014/birds/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!