“Hide and Seek,” 1888

For years I’ve loved a painting in the permanent collection of the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. “Hide and Seek,” 1888, by William Merritt Chase, never fails to bewitch me: the play of dark and light, the sense of a photo having been snapped in mid-action, the feeling that you’ve entered a world that propels you back to your own childhood. You feel the excitement of the game; hear the tapping of feet on that gleaming floor. Yet the picture has a mysterious element, one that hints at thresholds, leaving childhood behind, even going through a final door into blinding light: is it harsh or benevolent?

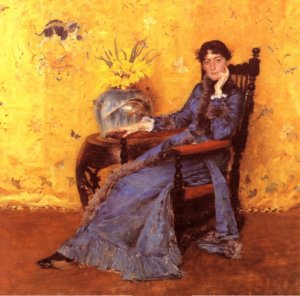

“Portrait of Dora Wheeler,” 1883

Enough of that blather. You get the idea. But while the picture knocks me out, I knew next to nothing about the artist. A recent Phillips Collection retrospective of this influential artist’s career—spanning the late 1800s and early 20th century—was a revelation. Chase, an American who trained abroad as a young man, cut a dashing figure in his ornate 10th Street studio in New York City. Despite his eccentricity and reputation as a bon vivant, he was a devoted family man and a respected teacher whose Chase School became the Parsons School of Design.

The show—some 70 works drawn from museums and private collections all over the country— was organized chronologically and by subject: historical genre paintings, landscapes, the seaside, domestic interiors, public parks. All were delightful. But on my second visit, I found myself most drawn to Chase’s portraits.

“James Abbott McNeil Whistler,” 1885

“Portrait of Dora Wheeler,” painted in 1883, was intended as an exhibition piece, showing off Chase’s formidable skills. Dora Wheeler, a former student, was a textile designer in the same 10th Street building as Chase’s studio. This large oil painting, with its thoughtful sitter and brilliant yellow background, won an honorable mention at the Paris Salon, but was generally panned by New York critics, as far too “radical a departure from convention.” The image of Wheeler was thought to be “lost” in the sea of textured brocade.

“The Young Orphan (At Her Ease),” 1884

Surprise! I did know another of Chase’s paintings. Coming upon his portrait of James McNeil Whistler was like running into an old friend. Bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1918, I’d seen it many times. In 1885, Chase, long an admirer of Whistler, paid him a visit in London on his way to Madrid. The older artist suggested the young Chase stay and allow time for each of them to paint the other’s portrait. Chase’s portrait was intended as an homage, using many of Whistler’s own techniques and conventions: free brushwork, a somber palette, the figure floating in space. Whistler, though, thought it an unflattering “abomination,” and may well have destroyed his own portrait of Chase in a fit of pique.

“Meditation,” 1886

“The Young Orphan,” painted the year before, is arresting. It’s only paint on canvas, we know that, but we also feel that we are looking at a real person who once lived and is still alive somehow. The model likely came from the quaintly named Protestant Half Orphan Asylum next door to the 10th Street studio. The exquisitely detailed hair, and lush rendering of the chair is tour de force painting. The picture evokes the influence of Whistler and John Singer Sargent, as the girl floats in a sea of crimson, her black dress an almost abstract shape.

“Lydia Field Emmet,” 1892

Chase also shows off his ability to render texture in “Meditation,” 1886. The drapery in the background looks like watered silk, or imitates brushstrokes. This intriguing portrait (presumably of his wife to be, Alice Gerson, whom he married the following year) is done in pastel, not oil. Hard to believe. Anyone who’s worked in the medium knows how hard it is to control, and how ambitious it would be to take on such a large, complex composition. I love the sitter’s direct, yet somehow veiled gaze. She’s likely thinking interesting thoughts about the painter.

Another student of Chase’s, Lydia Field Emmet, became a noted society painter and designer of Tiffany glass. In this 1892 portrait Chase again defies convention by posing her much as a noble gentleman would be seen in a classic Rembrandt or Frans Hals, painters Chase adored while studying in Europe. In researching Emmet, I learned, as I has suspected, she was related to dear friends of the same name, descendants of the Irish poet and rebel patriot, Robert Emmet. I again experienced that sizzle of connection: yes, she’s long dead and gone, but something in her gaze spoke to me. And I spoke back, telling her (in my head, of course) about the new additions to her long lineage who lived, until recently, not far from where her image now hangs in the Brooklyn Museum.

“Mother and Child (The First Portrait),” 1888

“Mother and Child (The First Portrait),” ca. 1888, is a dramatic full-length oil painting of Alice Chase and her first baby. The child appears about to wiggle out of its mother’s arms, while Alice herself is a static, monumental figure in her figured black robe. She seems about to turn toward the viewer, and although viewed in profile, has none of the hauteur of Lydia Field Emmet, as appropriate for the subject. Despite its intimate, domestic nature, Chase imbues the image with a grandeur and solemnity which surprised me. In a good way.

Art historians may debate whether William Merritt Chase was an American Impressionist, or a realist, but it seems to me he was both, able to capture light and skew his compositions in interesting and modern ways while communicating a very real sense of time and place. If you missed the show, take a look at this video: http://www.phillipscollection.org/exhibitions

A very fine exhibition catalogue is also available through the Phillips Collection store and at Amazon.com.

Enjoy!