“The Strand that Holds us Together,” 2014, by Carlee Fernandez

I must confess to an uneasy relationship with contemporary art. I often get the sense that I’m not in on the joke, or the materials seem strangely chosen, or it’s technically proficient, but cerebral. It’s probably generational, but much of the new art out there just doesn’t grab me. Or, worse, it’s a mild turn-off.

And so I approached the show at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC–a showcase for six young Latino artists, “Staging the Self”–with mild trepidation. Ninth in the Portraiture Now series, the artists on view are looking to “…rid portraiture of its reassuring tradition that fixes a person in time and space.” Right off the bat, I’m thinking with my geezer brain, “What’s wrong with time and space?”

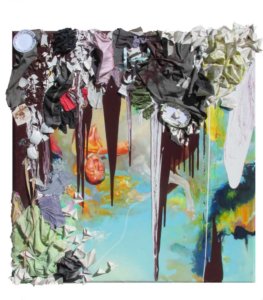

“forapieceofapple,” 2013, by David Antonio Cruz

The show opens with work by Carlee Fernandez, born in 1973 in Santa Ana, California. For some reason this lovely young woman chose to insert two plugs of bear fur up her nose as part of her “Bear Studies” series of photographs. And for some equally unknown reason the curators of this show chose to put this work on the cover of the program as its signature image. I’m not including it here, but if you’re curious, just google “Bear Studies.” Nor will I include her semi-nude antics in a bear suit, all of this having to do with her “challenging her physical identity,” and “exploring the boundaries of individuality.” As a card-carrying curmudgeon, this kind of talk makes me nervous. But Fernandez did reach me—and held me—with a striking image entitled, “The Strand that Holds Us Together,” 2014, an archival pigment print on rag. Here, her hand and her father’s hand appear side by side, almost as if they’re one person’s hands—a moving portrait of father and daughter.

“Mom healing me from my fear of iguanas by taking me to the park and feeding them every weekend, ca. 1994,” 2012, by Karen Miranda Rivadeneira

David Antonio Cruz, born 1974, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, explores “…untold aspects of the Puerto Rican diaspora experience,” bringing to it a “queer” perspective. This is intriguing, but the work is either so much an in-joke, or I am so impossibly straight, that I couldn’t see anything uniquely queer in it. I did enjoy the work—assemblages of crockery, fabric, ephemera, and spilled paint with cunning little portraits tucked away behind the ruched fabric. “forapieceofapple,” 2013, enamel, gold leaf, fabric, broken plates, paper planes made from Ellis Island documents, was an absorbing and unusual piece of art.

“Mom curing me from the evil eye, 1991,” 2012, by Karen Miranda Rivadeneira

The work of Karen Miranda Rivadeneira, born in 1983, in New York City, deals with “identity and intimacy” as she restages scenes from her childhood that were never recorded and may never have actually happened. With captions penned at the bottom as in a family album, this work presented very specific and personal scenes. I particularly liked “Mom healing me from my fear of iguanas by taking me to the park and feeding them every weekend, ca. 1994,” a 2012 digital C-print scanned from a 6X6 negative. I can easily identify with Karen’s rigid body as the iguanas swarm her banana-wielding mother. The banyan tree seems to sympathize with Karen, enveloping her in its roots. The mix of reportage and fiction here feels authentic and touching. Evidently Karen and her mother really did travel to Ecuador for the iguana cure. “Mom curing me from the evil eye, 1991,” also 2012, recreates another scene from childhood in a wonderfully evocative image.

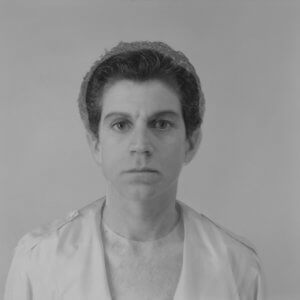

“Duplicity as Identity, 50%,” 2008, by Maria Martinez-Canas

Maria Martinez-Canas, born 1960, in Havana, Cuba and raised in Puerto Rico, overlays nine images of her (in a picture taken at about the same age as her father’s photograph) on her father’s face in increasing ratios, or “incremental mixes.” Over nine images, his face, surrounded with a faint halo of her hair, gradually morphs into her face. What is meant by “duplicity” in this case? Is it a play on “duplicate,” or is the artist implying she or her father are deceptive, dishonest, or misleading? Unlike “The Strand that Holds us Together,” this series of images left me cold. Clever, yes, and beautifully produced, but these faces reflected little or no emotion. One wonders about the seemingly chilly father-daughter relationship, as in “Duplicity as Identity, 50%,” an archival pigment print mounted on aluminum, 2008.

“This is Ours–AJ,” 2011, by Michael Vasquez

Michael Vasquez, born 1983 in St. Petersburg, Florida, gives us raw and unvarnished images of the “male world of the streets and gang life” from a “perspective of a boy growing up without a father figure.” Particularly powerful was “This is ours—AJ” (acrylic, 2011), exploding on the canvas with all of Florida’s knock-your-eye out color, as body art becomes the art. I was enchanted by the small “Hennessy Shots,” mixed media on paper, 2010. This is the piece I would have taken home, if I could. So often, I give my heart to the small works on paper.

“Hennessy Shots, ” 2010, by Michael Vasquez

Finally, Rachelle Mozman, born 1972 in New York City, employs a “documentary style” in her “fictional narratives” in which her mother plays various roles—a pair of twins, one with darker skin, a maid, a rich woman, exploring the “conflict of vanity, race and class within her.” In “El espejo,” 2010, in her maid incarnation, the mother looks almost accusingly at the viewer, while her elegant and pale-skinned doppelganger coolly observes herself in the mirror, tucking a strand of hair into her French twist. Again, while provocative, Mozman’s mise en scenes were remote,

“El espejo,” 2010, by Rachelle Mozman

lacking the juicy immediacy of Rivadeniera’s, and leaving me wanting more.

See what you think and let me know. http://www.npg.si.edu/exhibit/exhstagingself.html

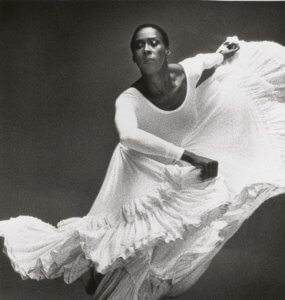

Fraught with psychological overtones, the image led Burgess to make this new dance expressing “an emotional terrain of the mind” whose predominant theme is the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which feelings are unresolved.

Fraught with psychological overtones, the image led Burgess to make this new dance expressing “an emotional terrain of the mind” whose predominant theme is the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which feelings are unresolved. In this piece, Burgess’s characteristic spare, clean lines are punctuated with sharp, pecking arm and hand gestures, and an idiosyncratic pulling motion that seems to draw an invisible thread from inert figures on the floor. Fluid, organic movements mingle and merge in hypnotic ways, the dancer’s faces showing more and more eye contact and emotion—ranging from wariness to openness to outright fear—as the dance progresses. This churning intensity propels the dancers upward into spectacular lifts and downward into curled resting positions. Twice, male dancers lift women and hold them aloft, straight as exclamation points, like “pillars of emotion,” to use Burgess’ words.

In this piece, Burgess’s characteristic spare, clean lines are punctuated with sharp, pecking arm and hand gestures, and an idiosyncratic pulling motion that seems to draw an invisible thread from inert figures on the floor. Fluid, organic movements mingle and merge in hypnotic ways, the dancer’s faces showing more and more eye contact and emotion—ranging from wariness to openness to outright fear—as the dance progresses. This churning intensity propels the dancers upward into spectacular lifts and downward into curled resting positions. Twice, male dancers lift women and hold them aloft, straight as exclamation points, like “pillars of emotion,” to use Burgess’ words. While exploring the uncertainty of short relationships that “are not love, not trusting,” the dance shows us the various effects of touch—it can soothe and it can hurt. Hands caress, appear to strike, swoop in crane-like arches, and, in staccato bursts, express frustration and tension between partners. Dancers also leaned their heads on their partner’s shoulders, backs, and arms, allowing momentary respite from the mood of suspended anxiety and bringing a fleeting sweetness into the mix. Not that this sustained emotion is hard to watch. Quite the contrary. It would have been impossible to look away.

While exploring the uncertainty of short relationships that “are not love, not trusting,” the dance shows us the various effects of touch—it can soothe and it can hurt. Hands caress, appear to strike, swoop in crane-like arches, and, in staccato bursts, express frustration and tension between partners. Dancers also leaned their heads on their partner’s shoulders, backs, and arms, allowing momentary respite from the mood of suspended anxiety and bringing a fleeting sweetness into the mix. Not that this sustained emotion is hard to watch. Quite the contrary. It would have been impossible to look away. The complex choreography, seemingly propelled by the swirling, eddying music, conjures bodies of water meeting, joining and flowing in sometimes gentle and sometimes turbulent ways. I was particularly struck by the complex whorl of movement in which the woman lifted the man, and another pairing in which the woman rolls her head and upper body along the outstretched arm of the man. The work is filled with many such strikingly original moments.

The complex choreography, seemingly propelled by the swirling, eddying music, conjures bodies of water meeting, joining and flowing in sometimes gentle and sometimes turbulent ways. I was particularly struck by the complex whorl of movement in which the woman lifted the man, and another pairing in which the woman rolls her head and upper body along the outstretched arm of the man. The work is filled with many such strikingly original moments. “Confluence” ends with a woman placing her hand on a fallen man’s body. Her expression is unreadable—does she feel victorious, dominant, or tender? It’s a moving end to a piece in which the viewer is pulled into a darkly absorbing psychological space. Doris Humphrey would have loved it!

“Confluence” ends with a woman placing her hand on a fallen man’s body. Her expression is unreadable—does she feel victorious, dominant, or tender? It’s a moving end to a piece in which the viewer is pulled into a darkly absorbing psychological space. Doris Humphrey would have loved it! And, if you haven’t seen it yet, “Dancing the Dream” is on view in the National Portrait Gallery until July 13, 2014.

And, if you haven’t seen it yet, “Dancing the Dream” is on view in the National Portrait Gallery until July 13, 2014.