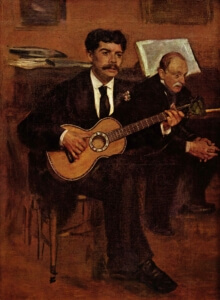

“Lorenzo Pagans,” 1871-72, Musee d’Orsay

At my reserved time slot, properly masked and distanced, I walked into the National Gallery of Art on a beautiful September day. It was like going home after a six-month exile and I was more than ready to see some art, in the flesh, so to speak. And what a treat awaited – Degas at the Opéra, a celebration of the Paris Opéra’s 350th anniversary. The Musée D’Orsay, the Musée de l’Orangerie, and the National Gallery joined forces to gather paintings, works on paper, and one sculpture by the great opera and dance devotee.

Degas adored the Paris Opéra – the wonderful old building, the dance classes and rehearsals, and the fantastical stage performances. He also didn’t shrink from the seamier side of the Opéra ballet of the mid-to late 1800s. Had the #metoo movement been afoot (pun intended), the young women of the corps de ballet would have been tweeting their hearts out.

“Portrait of Mille Fiocre in the Ballet La Source,” 1867-68, Brooklyn Museum

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Degas, born into a well-to-do family, was introduced early to the joys of music at salons in his home. This portrait of the soulful Lorenzo Pagans was also a portrait of Degas’ father, seen with his head framed by sheet music. It was the only portrait Degas ever painted of his father of whom he was very fond. Unfettered by the need to earn money, and with encouragement from his well-to-do parents, Degas was free to develop both his talent and his love of the opera, in which dance had a starring role.

“La Source,” likely Degas’ first opera ballet painting, depicts what appears to be an idealized history scene, but is a faithful rendering of the ballerina Eugenie Fiocre, dressed for her role as the melancholy Nouredda, bride of the khan. Glad you asked. Yes, the set did have a stream running through it and a live horse made an appearance, too. Look between the legs of the horse and you can make out a discarded pair of pale pink ballet slippers.

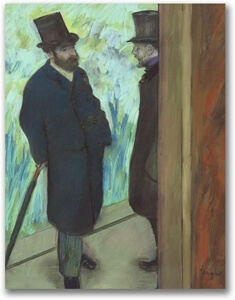

“Friends at the Theater,” 1879, Musee d’Orsay

Degas was just as interested in the patrons of the Opéra as he was the performers. In “The Two Friends,” we see his dear friend, Ludovic Halévy, conversing with another gentleman. It was Halévy, an avid connoisseur, who first introduced Degas to the Opéra. I love the strong vertical element setting off the two men, and how their dark suits and tall hats are crisply silhouetted against the painted stage flat.

“Robert le Diable,” brings us down to the orchestra level, the vaunted territory of season ticket holders, all men. (Women were seated upstairs, in the boxes). At this point, the Meyerbeer opera was somewhat shopworn, and, as you can see, the gentleman with the opera glasses to the left is far more interested in who might be up in the boxes than he is in the action on the stage. Floating above the orchestra we see reprobate nuns, risen from the dead, performing a suggestively bacchanalian dance, as only a fallen nun can.

“The Ballet from Robert le Diable,” 1871, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

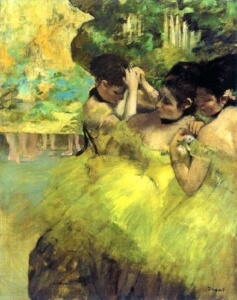

Throughout this lush show, Degas’ use of color—in his marvelous pastels and oil paintings—is a standout. I loved “Yellow Dancers,” both for the eye-popping citrus yellow, but also for the wonderfully intimate poses of the dancers in the wings. First and foremost, Degas thought of himself as a draftsman and used line to express his love of the human form. He would sketch the same pose over and over, finding the volume, weight, and characteristic expression in each. He created a vocabulary of dancers’ poses – yawning, back scratching, stretching, flexing the foot, extending the leg—which he could draw upon when a composition called for it.

“Yellow Dancers in the Wings,” 1874-76, Art Institute of Chicago

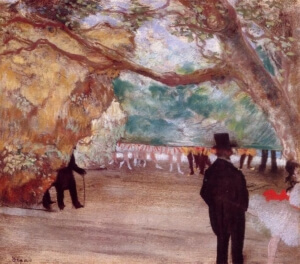

In “The Curtain,” a dancer flees from a top hatted man. Her panicked eye is barely visible as she disappears out of the frame, her red sash trailing. Men also lurk to the left, and from behind a flat their trousered legs mingle with those of the dancers. Wait. What’s going on here? As season ticket holders, these men enjoyed the privilege of openly stalking the young dancers, ogling them from the wings or the front seats of the orchestra. Degas depicts them with a stark and sinister air; their constant presence serves as a reminder that the dancers—often only girls—were generally from poor families. If they showed talent, they would be pushed into a profession that was only a cut above prostitution. Several paintings here show the girls’ bonneted mothers coaching them at auditions or seated in the galleries watching rehearsals. They were complicit; surely they knew what peril their daughters might face in the life of a dancer.

“The Curtain,” 1880, National Gallery of Art

Around 1880, inspired by Renaissance alter panels and Japanese woodblock scrolls, Degas began to create frieze-like pictures such as “The Dance Lesson,” the first of these horizontal compositions. An exhausted dancer in a red shawl slumps on a double bass while the strong line of the dark brown panel draws the eye to two other dancers, one adjusting her sash, and on to a group of dancers by the barre in the strong light of the windows.

“The Dance Lesson,” 1879, National Gallery of Art

The same elements appear in “Dancer Climbing the Stairs,” but are now radically changed. A dancer climbs a staircase to the rehearsal room as two other dancers follow, just barely visible at the far left of the picture. One turns to the other, as if in the midst of conversation, and, even though we barely see the third dancer’s face, the swirling motion creates a sort of eddy in the wake of the climbing dancer which increases the sense of upward momentum. All this arrested action is even more impressive as we learn the staircase never existed.

“Dancers Climbing the Stairs,” 1886-90, Musee d’Orsay

Across the room from the frieze paintings are a series of fans Degas created in a time of financial pinch when the Degas family banking enterprise went belly-up. Here, too, we see the Japanese influence as Degas plays with compositions in a constrained space. One has a special significance. Among the first he created, this fan features Spanish dancers and musicians. Although he’d planned to sell the fans, he gave this one to his friend, Berthe Morisot. Later, she featured the fan in her own painting, “The Sisters,” also found in the National Gallery’s permanent collection.

“The Sisters,” 1869, by Berthe Morisot, National Gallery of Art

And now – the moment you’ve likely been waiting for: “The Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen,” the only sculpture Degas exhibited in public in his lifetime. The National Gallery proudly owns a large collection of Degas waxes, and this young girl, with her perfect turnout, forward thrust hips, and pensive, long-suffering face, is perhaps the best known. She wears tights, a real fabric tutu, dance slippers, and a satin ribbon in her hair (human and horsehair). I gazed into her face and wondered what she was thinking as she posed for the artist. Today, we find her charming—I certainly did—but in her day, most viewers did not find her charming at all. When she debuted at the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition in 1881, the critics, fed on a more conventional diet of idealized classical sculpture, savaged her as “odiously ugly,” an “Opera rat” unworthy of elevation to art.

On that melancholy note, the show came to an end, and as I walked out of the last gallery, I found myself in a makeshift gift shop, where our dear little Opéra rat adorns everything from scarves to tote bags.

“Little Dancer Aged Fourteen,” 1878-1881, National Gallery of Art

Do try to get there, if you’re anywhere near DC. This glorious show, featuring a number of video clips of the ballets depicted in the paintings, is up until October 12, 2020, proof that not everything in this blighted year is toxic.

Indeed, Degas at the Opéra is a tonic.

You can get your timed entry slot here:

https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2020/degas-opera

“Spanish Dancers and Musicians,” 1868-69, National Gallery of Art

releases her to dash forward again.

releases her to dash forward again.

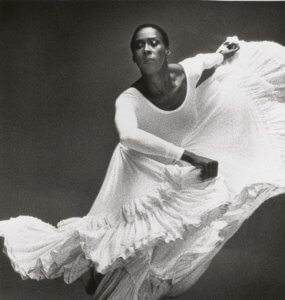

Fraught with psychological overtones, the image led Burgess to make this new dance expressing “an emotional terrain of the mind” whose predominant theme is the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which feelings are unresolved.

Fraught with psychological overtones, the image led Burgess to make this new dance expressing “an emotional terrain of the mind” whose predominant theme is the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which feelings are unresolved. While exploring the uncertainty of short relationships that “are not love, not trusting,” the dance shows us the various effects of touch—it can soothe and it can hurt. Hands caress, appear to strike, swoop in crane-like arches, and, in staccato bursts, express frustration and tension between partners. Dancers also leaned their heads on their partner’s shoulders, backs, and arms, allowing momentary respite from the mood of suspended anxiety and bringing a fleeting sweetness into the mix. Not that this sustained emotion is hard to watch. Quite the contrary. It would have been impossible to look away.

While exploring the uncertainty of short relationships that “are not love, not trusting,” the dance shows us the various effects of touch—it can soothe and it can hurt. Hands caress, appear to strike, swoop in crane-like arches, and, in staccato bursts, express frustration and tension between partners. Dancers also leaned their heads on their partner’s shoulders, backs, and arms, allowing momentary respite from the mood of suspended anxiety and bringing a fleeting sweetness into the mix. Not that this sustained emotion is hard to watch. Quite the contrary. It would have been impossible to look away. “Confluence” ends with a woman placing her hand on a fallen man’s body. Her expression is unreadable—does she feel victorious, dominant, or tender? It’s a moving end to a piece in which the viewer is pulled into a darkly absorbing psychological space. Doris Humphrey would have loved it!

“Confluence” ends with a woman placing her hand on a fallen man’s body. Her expression is unreadable—does she feel victorious, dominant, or tender? It’s a moving end to a piece in which the viewer is pulled into a darkly absorbing psychological space. Doris Humphrey would have loved it! And, if you haven’t seen it yet, “Dancing the Dream” is on view in the National Portrait Gallery until July 13, 2014.

And, if you haven’t seen it yet, “Dancing the Dream” is on view in the National Portrait Gallery until July 13, 2014.

During the interval between performances, Fredmann talked about Natalia Gonchorova’s complete redesign of the Firebird set (see my earlier blog post

During the interval between performances, Fredmann talked about Natalia Gonchorova’s complete redesign of the Firebird set (see my earlier blog post  If you come to the August 11, 2013 performance by Dana Tae Soon Burgess you’ll see original choreography premiered in a suite of dances “inspired by the spirit of the Ballets Russes.” Come early! There will be two performances at 1:30 and 3:30, best seen from the front rows or standing in the back of the performance space. The riser is low enough to provide a limited line of sight much further back than the third or fourth row.

If you come to the August 11, 2013 performance by Dana Tae Soon Burgess you’ll see original choreography premiered in a suite of dances “inspired by the spirit of the Ballets Russes.” Come early! There will be two performances at 1:30 and 3:30, best seen from the front rows or standing in the back of the performance space. The riser is low enough to provide a limited line of sight much further back than the third or fourth row.