Aerial view of the NGA roof terrace

Well worth the three-year wait, the newly redesigned and refurbished East Building of the National Gallery of Art has reopened. Perry Chin, a colleague of I.M. Pei, architect of the original, undertook the extensive, if subtle reworking. First opened in 1978 to house modern and contemporary art, the building is comprised of interlocking triangles reflecting the shape of the original parcel of land.

The works now on view incorporate more than 200 of the NGA’s plunder of the now defunct Corcoran Gallery’s collection (an astonishing 8,766 works). As reported recently in the Wall Street Journal, the NGA got to choose whatever it wanted from the Corcoran’s collection (dream job, or what?) after the dear old gallery’s financial demise. Now many choice pieces benefit—as do we—from the smart reworking of gallery space.

“Hahn/Coick,” 2013, by Katharina Fritsch

For my first visit, I decided to start at the top—the new outdoor roof terrace—and work my way down. Never made it to the bottom. Another day, another blog!

With a sweeping view of Pennsylvania Avenue, the terrace houses modern sculpture, including George Rickey’s mesmerizing “Divided Square Oblique,” 1981. I sat on a bench and watched those stainless steel wand swing and dip to form seemingly endless combinations. Soon a museum employee scuttled around to polish the “Do Not Touch” signs embedded in the floor near each sculpture. A good thing, too, as Katharina Fritsch’s “Hahn/Cock,” 2013, polyester resin, begged to be touched. Seen here through the stainless pipes of Kenneth Snelson’s “V-X,” 1968, the monumental rooster is sure to become a favorite selfie spot.

“Three Motives Against a Wall No.1” 1958, by Henry Moore

Just inside the door leading from the sculpture terrace to Tower One, I was captivated by the amusingly named “Three Motives against a Wall, Number One,” 1958, a small Henry Moore bronze. This mix of small delights and monumental construction is one of the charms of the East Building. Unlike, for example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, whose vast entry/atrium seems to exist more to elevate the architect than to house art. I could go on—think “starchictects” we know and don’t love—but why, when there’s so much to love here?

“Stations of the Cross,” 1966, by Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko, Classic Paintings

Namely, the spare “Stations of the Cross,” 1966, in the new tower gallery. Comprised of fourteen paintings by Barnett Newman, this work was first exhibited at the Guggenheim in 1966. Since then, these paintings have received lots of critical acclaim and a good bit of distain as well. Newman has said that the line in his paintings—he called them “zips”—symbolized an individual man or woman, reduced to his or her most essential representation. Raised Jewish in New York City, are we to think from the title that Newman converted to Catholicism? No, as the wall text explains. These works, meant to be seen sequentially, explore a single theme. Jesus’s cry on the cross—“Why have you forsaken me?”—is also our existential question as humans. What are we doing here and what comes next?

“Shell No. 1,” 1928, by Georgia O’Keeffe

The adjacent gallery, also lit by filtered tower light, gives us “Mark Rothko: The Classic Paintings.” Here in early works, the artist explores basic human emotions of “…tragedy, ecstasy, doom.” Stepping into this gallery, we Washingtonians think immediately of the Rothko room at the Phillips Collection. The comparison works in favor of both institutions. The small room at the Phillips allows viewers to be immersed in the pulsing color of the paintings, up close and personal. And although the tower room is considerably larger, the same reverential feeling abides. Taken as a whole, the Newman and Rothko tower galleries feel like a sacred space.

Walking down the staircase leading from Tower One to the Upper Level (Modern Art from the Collection), it seemed as if every inch had been buffed and polished. Or maybe the staircase is one of the new ones. I’m hoping to take a tour that will make clear how the building was renovated. As it stands, it all feels so fresh and new that it’s hard to recall how the original spaces were configured.

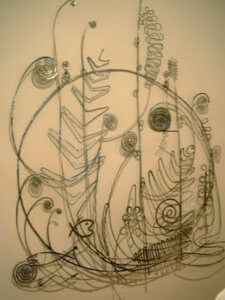

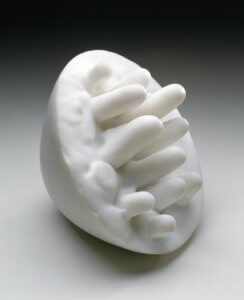

“Germinal,” 1967, by Louise Bourgeois

In the “Dada and Beyond” gallery, the curators have filled a case of small oddities that coexist so beautifully it’s as if they were made to be together. Georgia O’Keeffe’s beguiling “Shell No. 1,” painted in 1928, hangs with several Joseph Cornell boxes. These are kindred spirits of Betye Saar’s “Twilight Awakening,” made fifty years after O’Keeffe’s luminous shell. “Germinal,” a 1967 marble sculpture by Louise Bourgeois possesses the sly humor of its casemates. Notions of theft flit through the mind. They’re all small enough to fit in…oh, never mind.

Walking through the gallery entitled “Birth of Abstraction,” I passed a flock of Brancusi sculptures, each mounted on gorgeous wooden bases, to find Wassily Kandinsky’s “Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle),” 1913. The piece does roil and splash, colors hitting colors with exuberance, but not quite the violence suggested by the title. How fresh and modern this picture feels103 years later.

“Improvisation 31 (Sea Battle)”, 1913, by Wassily Kandinsky

Color also rules in Hans Hofmann’s “Autumn Gold,” 1957. I can get lost in this composition, enjoying the tactile application of paint, how colors slap up against other colors. Clearly the artist loved paint for paint’s sake.

Much more controlled is Gene Davis’s “Black Popcorn,” 1965. Hung in the space entitled, “Color Field and Edge,” it’s an old friend from the Corcoran collection. Here the color is sparked by black stripes. The so-called “Washington Color School” gets ample billing here, thanks to the NGA’s Corcoran windfall.

“Autumn Gold,” 1957, by Hans Hofmann

Nearby hangs Sam Gilliam’s “Relative,” 1969. Gilliam, now 82, is breaking new ground with a monumental piece commissioned by the Museum of African American History and Culture. Can’t wait to see it. Gilliam’s work, always hard to categorize, evolved from figurative work to the breakthrough in which he abandoned the frame entirely. In the “draped” paintings, the canvas is painted with abstract images and then hung—from walls, ceilings, even the front of a building in Philadelphia. Rather than hanging limp or inert, “Relative” seems to march across the wall with great energy.

“Black Popcorn,” 1965, by Gene Davis

After an hour and a half, I’d savored the art (oh, those shimmering Morandi still lifes!), and also reveled in the building itself, gleaming and full to bursting, topped off by that friendly alien, the Alexander Calder mobile. Later, I was stunned to learn that it was the final monumental piece commissioned from Calder, and that he died shortly after the untitled mobile was installed in the East Building. Knowing that, I’ll see it just a bit differently, but always with awe and affection.

“Relative,” 1969, by Sam Gilliam

Good news: the terrace café has reopened, albeit offering packaged food and get-it-yourself coffee, sadly, but still…you can sip your coffee and nibble on your scone and watch the Calder mobile languidly traverse that extraordinary space.

“Untitled,” 1978 by Alexander Calder

For a glimpse of how the precision work was done to create the building in the 1970s, click the link below and view a twelve-minute documentary which also shows Calder, Robert Motherwell, and Henry Moore in collaboration with architect I.M. Pei and then-museum director, the stylish impresario, J. Carter Brown.