Sculpture near Hirshhorn Museum

Hey, howdy! What’s keeping you sane-ish in these strange and trying times? For me, it’s been hour-long walks near our Southwest DC condo. But with museums and galleries closed, I’m really missing art. Sure, I could tour museums online, but, as we all know, there ain’t nuthin’ like the real thing. One day, as I trekked up to the National Mall, I woke up to the art right under my nose. I’d walked past sculptures by Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Anthony Caro, without—shame on me—really seeing them.

Truth to tell, works on paper or paint on canvas have always spoken to me more strongly than sculpture. But if sculptures are all I’ve got, I vowed to go back and really see them. First, I dove into Seeing Slowly: Looking at Modern Art, by art dealer Michael Findlay. If I’d walked by all those works of art for the past three months, all the while bemoaning the lack of art in my life, I clearly needed help. Findlay, despite his many years of scholarship, figured out how to see works with new eyes. Easy-to-master tactics result in a state of mindfulness in which we can be open to art and—maybe, maybe not—be deeply moved by it. There is no right or wrong. If the piece moves you, that’s all you need to know.

So, off I went again to the Mall, first stopping to sit on a bench, close my eyes, and breathe deeply for several minutes. (Step One in the Findlay method.) Next, I tried to let the art pick me (Step Two), rather than looking around for something “important,” or a piece by a well-known artist.

So, off I went again to the Mall, first stopping to sit on a bench, close my eyes, and breathe deeply for several minutes. (Step One in the Findlay method.) Next, I tried to let the art pick me (Step Two), rather than looking around for something “important,” or a piece by a well-known artist.

The giant red sculpture just ahead spoke to me—loudly. Step Three: DO NOT read the identifying plaque. You don’t need to know who made it. Let it speak to you on its own. Findlay suggests spending at least three minutes with a work to see what it might give us (Step Four). I checked my watch and started looking. The sculpture looked familiar and I was pretty sure I’d seen similar works crawling hugely over hill and dale at the outdoor Storm King Art Center in upstate New York, but I tried to put that out of my mind.

At first, I saw only the enormous red-orange I-beams arranged at various angles, with one V-shaped piece dangling by a cable. As I gazed, words began to float up in my mind: forthright, masculine, audacious, thrusting, grounded. But that V. That V was oddly touching, hanging out there at the mercy of the wind, moving and changing as it turned. I noticed several other Vs in the composition and, as the light changed, the sculpture began to look like an enormous drawing.

At first, I saw only the enormous red-orange I-beams arranged at various angles, with one V-shaped piece dangling by a cable. As I gazed, words began to float up in my mind: forthright, masculine, audacious, thrusting, grounded. But that V. That V was oddly touching, hanging out there at the mercy of the wind, moving and changing as it turned. I noticed several other Vs in the composition and, as the light changed, the sculpture began to look like an enormous drawing.

And then something happened. I felt a welling of emotion, of mysterious communion, of awe. The sensation was all the more delicious for being unexpected. In the end, I’d spent eight minutes with the piece and was reluctant to leave it. I suspect I’ll return again and again, seeking it out like an old friend.

Next, a bright and shiny object caught my eye: a life-sized stainless steel character out of a Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale – a peddler? I noticed all the stuff in his basket: a floppy rabbit, eggs, loaves of bread, cheeses, a ham. In the early days of Covid food shortages, this guy would have been a welcome sight. With his antique clothing – spats, clogs, a flowing smock, a jaunty cap, and that pipe – he was a kitschy voyager, back from “olden days.” Standing in front of the flying saucer Hirshhorn Museum, the effect was jarring.

I circled the sculpture, all burnished and gleaming in the late-morning sun, I wasn’t sure how I felt about him. After about three minutes, a creepy sizzle from his eyes gave me the sense he was watching me. As I moved, his eyes followed. He seemed to say, with a leer, You have no idea who I am or where I came from, do you, honey? I shuddered. No epiphany with this guy, no communion, no awe.

I circled the sculpture, all burnished and gleaming in the late-morning sun, I wasn’t sure how I felt about him. After about three minutes, a creepy sizzle from his eyes gave me the sense he was watching me. As I moved, his eyes followed. He seemed to say, with a leer, You have no idea who I am or where I came from, do you, honey? I shuddered. No epiphany with this guy, no communion, no awe.

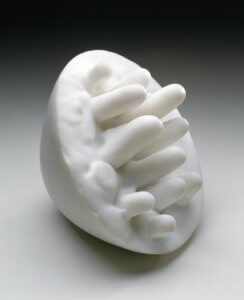

I was relieved to move on and soon came upon two large shapes on a pedestal. Dappled under trees, this piece of abstract art sits overlooking the brooding Rodins in the Hirshhorn’s sunken sculpture garden.

I was relieved to move on and soon came upon two large shapes on a pedestal. Dappled under trees, this piece of abstract art sits overlooking the brooding Rodins in the Hirshhorn’s sunken sculpture garden.

Now I was reminded of another Findlay dictum: to adopt an attitude, not only of seeing, but of watching a work of art. What does it do? Is it alive? As I walked around the sculpture, the bronze shapes did feel animated. I sensed how they yearned toward one another. With their bronze hide-like surface, they sported flippers, fins, arms, leg-like stumps. The shape on the right had the most inquisitive beak and the figure on the left reminded me of Martha Graham writhing in a tube-like sock, her arms protruding now and then to create an alien animal.

After three minutes of circling, I returned to the front of the sculpture. As I watched, the space between the figures began to vibrate and I swear I saw them move toward each other. The energy charge between the two creatures was electric. As I circled the sculpture again, it struck me that those shapes could never have taken any other shape that the ones they’d become. Broad and comforting, maybe male and female, maybe not, the pull they exerted on one another was palpable.

After three minutes of circling, I returned to the front of the sculpture. As I watched, the space between the figures began to vibrate and I swear I saw them move toward each other. The energy charge between the two creatures was electric. As I circled the sculpture again, it struck me that those shapes could never have taken any other shape that the ones they’d become. Broad and comforting, maybe male and female, maybe not, the pull they exerted on one another was palpable.

The six-minute experience with these two figures was entirely satisfying, but far quieter than my encounter with the big red sculpture, and far more pleasant than my encounter with Mr. Peddler.

So there you have my experiment in seeing slowly. I highly recommend trying it with the public art where you live. Fortunately for me, Washington, DC is blessed with a large quantity of outdoor art, and as I get more and more hooked on sculpture, I’ll return to this space with more slow observations.

So there you have my experiment in seeing slowly. I highly recommend trying it with the public art where you live. Fortunately for me, Washington, DC is blessed with a large quantity of outdoor art, and as I get more and more hooked on sculpture, I’ll return to this space with more slow observations.

If you’re not in the least curious about who made these works, you can stop reading now.

But if you are, the ten-ton red sculpture, “Are Years What? (For Marianne Moore),” was created by Mark di Suvero in 1967. Moore’s poem, “What Are Years?” seems a remarkably apt one for our times. Click here to hear di Suvero reading it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2l8TNZvLCPs

Or scroll down to the end of this post to read it yourself.

Marianne Moore

The stainless steel peddler, “Kiepenkerl,” was—yikes!—made by Jeff Koons in 1987. I hate Jeff Koons and his corny balloon dogs! But this work—a transitional one between his repurposed “readymades” (think latter-day Duchamp) and more original (if still outrageous) art. After listening to a Hirshhorn Museum curator’s talks on our man “Kiepenkerl,” I began to have some grudging respect for Koons. You can listen here: https://hirshhorn.si.edu/explore/fgt-kiepenkerl/

Finally, “Two-piece Reclining Figure, Points,” was created by Henry Moore in 1969-70 and cast in 1973. I love what he said about the two figures:

“The Two-Piece Reclining Figures must have been working around in the back of my mind for years, really. As long ago as 1934 I had done a number of smaller pieces composed of separate forms, two- and three-piece carvings in ironstone, ebony, alabaster and other materials. They were all more abstract than these. I don’t think it was a conscious or intentional thing for me to break up the figures in this way, but I suppose those earlier works from the thirties had something to do with it. . . . I did the first one in two pieces almost without intending to. But after I’d done it, then the second one became a conscious idea. I realised what an advantage a separated two-piece composition could have in relating figures to landscape. Knees and breasts are mountains. Once these two parts become separated you don’t expect it to be a naturalistic figure; therefore, you can justifiably make it like a landscape or a rock. If it is a single figure, you can guess what it’s going to be like. If it is in two pieces, there’s a bigger surprise, you have more unexpected views; therefore the special advantage over painting – of having the possibility of many different views – is more fully exploited.

The front view doesn’t enable one to foresee the back view. As you move round it, the two parts overlap or they open up and there’s space between. Sculpture is like a journey. You have a different view as you return. The three-dimensional world is full of surprises in a way that a two-dimensional world could never be.”

The front view doesn’t enable one to foresee the back view. As you move round it, the two parts overlap or they open up and there’s space between. Sculpture is like a journey. You have a different view as you return. The three-dimensional world is full of surprises in a way that a two-dimensional world could never be.”

[Henry Moore quoted in Carlton Lake, Henry Moore’s World, Atlantic Monthly, vol.209, no.1, January 1962, p.44]

What are Years, by Marianne Moore

What is our innocence,

what is our guilt? All are

naked, none is safe. And whence

is courage: the unanswered question,

the resolute doubt,—

dumbly calling, deafly listening—that

in misfortune, even death,

encourages others

and in its defeat, stirs

the soul to be strong? He

sees deep and is glad, who

accedes to mortality

and in his imprisonment rises

upon himself as

the sea in a chasm, struggling to be

free and unable to be,

in its surrendering

finds its continuing.

So he who strongly feels,

behaves. The very bird,

grown taller as he sings, steels

his form straight up. Though he is captive,

his mighty singing

says, satisfaction is a lowly

thing, how pure a thing is joy.

This is mortality,

this is eternity.

Visit this jewel box of a museum to clear your mind and spirit while feasting on one of the world’s most stunning collections of 19th and 20th century paintings, sculpture and African and Asian art. The private collection of Carmen and David Kreeger is housed in a 1967 Phillip Johnson home, a work of art in itself, with its Byzantine domes, travertine limestone clad walls, and interior courtyard filled with towering tropical plants.

Visit this jewel box of a museum to clear your mind and spirit while feasting on one of the world’s most stunning collections of 19th and 20th century paintings, sculpture and African and Asian art. The private collection of Carmen and David Kreeger is housed in a 1967 Phillip Johnson home, a work of art in itself, with its Byzantine domes, travertine limestone clad walls, and interior courtyard filled with towering tropical plants. After passing through the grand salon (Picassos to the right of you, Braques to the left of you!), you’ll come to a magnificent stairway, its railing clad in molten bronze grill work. Each of the rectangles and parallelograms is a work of art, no two alike, like links in an enormous necklace. Please touch! Descend the staircase, passing a Calder mobile, to the lower gallery. Here you’ll enjoy Yves Tanguy, Man Ray, Jean Dubuffet, Frank Stella, among others. Knockouts include Sam Gilliam’s vibrant “Cape” (1969), and Gene Davis’ candy striped canvas, untitled, so you can make up your own (1953).

After passing through the grand salon (Picassos to the right of you, Braques to the left of you!), you’ll come to a magnificent stairway, its railing clad in molten bronze grill work. Each of the rectangles and parallelograms is a work of art, no two alike, like links in an enormous necklace. Please touch! Descend the staircase, passing a Calder mobile, to the lower gallery. Here you’ll enjoy Yves Tanguy, Man Ray, Jean Dubuffet, Frank Stella, among others. Knockouts include Sam Gilliam’s vibrant “Cape” (1969), and Gene Davis’ candy striped canvas, untitled, so you can make up your own (1953). backsides. Both are lovely.

backsides. Both are lovely.