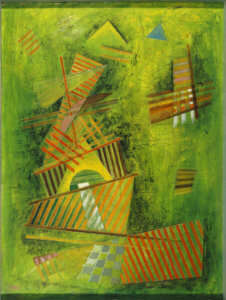

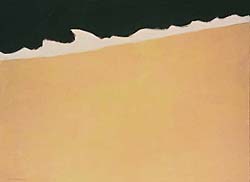

“Popocatepetl–Spirited Morning,” by Marsden Hartley, 1932

Sam Rose, the Washington DC attorney and real estate developer and his wife, Julie Walters, have built a rich and varied art collection over many years. Now, according to Sam, they’ve run out of wall space. Luckily for us, they’ve shared their collection in a show now at the National Museum of American Art in Washington, DC. The title—Cross Currents—didn’t immediately reveal curator Virginia Mecklenburg’s theme, but after watching an October 30, 2015 webcast, I got it. http://americanart.si.edu/multimedia/webcasts/archive/2015/crosscurrents/index.cfm

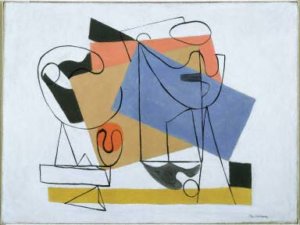

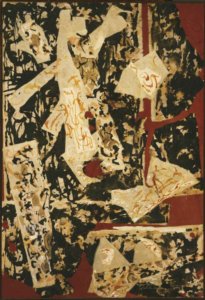

“Untitled Vertical,” by Jackson Pollock, 1949

The cross currents describe the flow of Americans who flocked to Paris in the early 1900s and were inspired by European modernists. Later in the mid-twentieth century, the flow reversed, with European artists drawn to the energy and dynamism of the “cubist, modernist” city of New York. Frankly, the show didn’t illustrate this theme as well as it might have, but no matter, it’s an engrossing experience. Hung in two generously sized galleries, it’s a large show, but not so huge as to be overpowering.

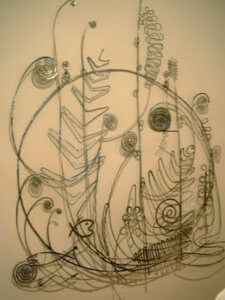

“Agricola IV,” by David Smith, 1952

The first to leap off the wall was Marsden Hartley’s “Popocatépetl, Spirited Morning—Mexico,” 1932, painted while Hartley lived in Mexico City. The image fuses the twin mythical volcanoes of Iztacc and Popo, the star-crossed lovers of Aztec myth, turned forever to glacial mountains by the gods. The icy white clouds of steam (or snowy boulders?) mount tension at the bottom of the picture, while the intense blue of the mountain is startlingly potent, seeming to contain unseen the orangey reds of latent eruption.

“Tete d’homme, profil” by Pablo Picasso, 1963

Much the same organic energy can be seen in Jackson Pollock’s “Untitled Vertical,” 1949. This painting is so fresh and new, so alive with calligraphic flourishes, that is seems timeless, evoking both the ancient and the new: Chinese and Japanese scrolls and revolutionary modern art. Pollack said, “When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing.” The meditative feel of this painting has much the same effect on the viewer. You can spend a long, pleasurable time in front of this image. The wall text observes that this painting represents “the most dramatic breakthrough in painting since Picasso’s cubism.” I agree.

“The DeVegh Twins,” by Alice Neel, 1975

I have a mad crush on David Smith. For good reason, don’t you think? “Agricola IV,” 1952, dates from a time that Smith hunted pieces of rusting farm implements near his studio in Bolton Landing, New York and welded them together. Evoking Calder’s wire portraits and tribal art, the Agricola series launched Smith’s career as an important modernist sculptor.

Walters and Rose have a serious addiction to acquiring Picasso, one of my least favorite artists. Sorry, but I think he’s over-rated. Millions would disagree. Vehemently. Julie and Sam among them, I’m sure. That said, along with a charming selection of his ceramic vessels, I did enjoy “Tête d’homme, profil,” 1963. This fellow appears to be a human megaphone with a lot to say. You can picture him, a fervent nihilist, perhaps, holding forth in a café, eyes popping out of his head, and a dense five o’clock shadow on his cheek. A telling portrait in which the abstraction has a wry purpose.

“Meringues,” by Wayne Thiebaud, 1988

Among the marvelous portraits seen here is Alice Neel’s “The DeVegh Twins,” 1975. Neel’s habit of showing unvarnished truth in her portraiture, slyly evoking the less attractive sides of many of her subjects is seen here. The girls, daughters of the artist and art restorer, Geza DeVegh, clearly have very different personalities. The girl on the left appears open, trusting, pliable and obedient, leaning fondly into her sister, while her twin signals “piece of work” – she’s difficult, intractable, and defiant. We don’t know what DeVegh made of this portrait, but we do know that many people who sat for Neel didn’t care for her often unflattering images and declined to hang them in their homes.

“Revue Girl,” by Wayne Thiebaud, 1963

Walters and Rose have acquired Wayne Thiebaud (this time a favorite of mine) in depth as well. In addition to pies (“Meringues,” 1988)—who can resist them—we see the same luscious sculpted surfaces in “Revue Girl,” 1963. A huge image, this woman towers above the viewer, amazon and totem in one. She, an anonymous dancer in a line of identical performers, is shown as singular and powerful. “There’s a lot of yearning,” Thiebaud said of his pies, cakes, and candies and the same could be said of this unattainable revue goddess.

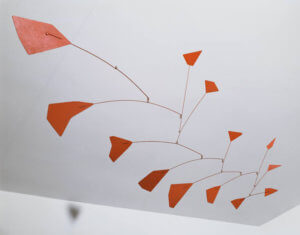

Roy Lichtenstein’s amusing, “Mobile III,” 1990, is a clear reference to Alexander Calder’s mobiles, with more than passing reference to Miro and Picasso. What a perfect summation of the “currents” flowing in this

“Mobile III,” by Roy Lichtenstein, 1990

exhibit. Of course, this “mobile” doesn’t move at all, perhaps symbolizing the final iteration of Mondrian’s impulse to make static art move. Whump—we’ve hit a wall. Now we have a cartoon of the original.

In “Black Scarf,” 1995, we meet another “goddess and sphinx,” Alex Katz’s muse and wife of 60 years, Ada. In this closely cropped portrait, Ada looks away from the viewer, at something tantalizingly off-camera. The flattened bill-board style is emblematic of Katz’s early style, which anticipated Pop Art, and here in its mature incarnation evokes a surprisingly broad range of emotions.

Picture 023

The great African-American artist, Elizabeth Catlett created “Stepping Out” in 2000. This image doesn’t fully capture the charm of this piece, the energy and forthright gait of this small woman as she sets out into the world in her finery, proud of the figure she cuts, and more than ready for what the world will dish out.

There’s a lot more to relish in this show. Fans of Joan Miro, Alexander Calder, Joseph Stella, Georgia O’Keefe, Richard Diebenkorn, David Hockney, Niki de Saint Phalle, Romare Bearden, Andy Warhol, and Fernando Botero will encounter wonderful works here, some perhaps never seen before. Three cheers to Julie and Sam!

“Stepping Out,” by Elizabeth Catlett, 2000

The show is up until April 10, 2016. http://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/archive/2015/crosscurrents/