“Bottle Rack,” 1920, by Marcel Duchamp

Unless you want to spend your Valentine’s Day at the Hirshhorn Museum here in DC (hey, not a bad idea…) you will have missed the surrealist exhibit Marvelous Objects. If you don’t drop everything and go, stick with this post. It’s a fascinating show, and I say that as not the world’s biggest fan of melting clocks, De Chirico’s chilly dreamscapes, or one-trick dadaist ponies, like Duchamp’s urinal. Ho hum. But the objects gathered here are, many of them, marvelous indeed.

The first gallery, entitled “The Object” does have some moldy figs including Duchamp’s 1920 bottle rack (making wonderful shadows on the gallery wall). From there on, surprises abound.

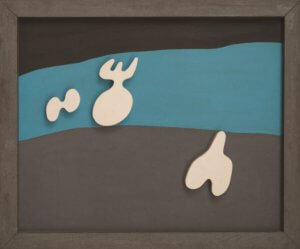

“Objects Placed on Three Planes, Like Writing,” 1928. by Jean Arp

Among them is a fabulous array of Jean Arp’s two-dimensional pieces. The wall notes tell us that Arp developed his biomorphic nature-based art as an antidote to the horrors of World War I. I do love these works, maybe because they remind me of the papier-maché bas-relief pieces my father created in the ’fifties and ’sixties. “Objects Placed on Three Planes, Like Writing,” 1928, is one of them. A lot of their charm lies in their whimsical titles, which evoke a smile and a twist of one’s initial perception of the piece. As in, “Head with Annoying Objects (Mustache, Mandolin, and Fly),” 1930, bronze.

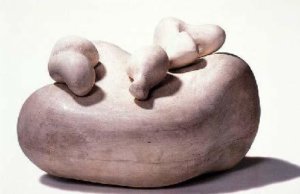

“Head with Annoying Objects…,” 1930, by Jean Arp

Alberto Giacometti said of his artistic process, “I search, groping to catch hold of the invisible white thread of the Marvelous that vibrates in the void; from it escapes facts and dreams with the sound of a stream running over small, precious, living pebbles…” This crystalline vision is dashed by “Woman with her Throat Cut,” 1932, a creepy thing lying in the middle of the space like road kill. In his excellent review, The Washington Post’s Philip Kennicott observes: “…it’s a strength of this exhibition that curator Valerie Fletcher is forthright about the almost inevitable direction that the freeing up of the creative mind would take so many of these men: straight to the rag-and-bone shop of misogyny.” I prefer the serene “Reclining Woman who Dreams,” bronze and paint, 1929.

“Reclining Woman Who Dreams,” 1929, by Alberto Giacometti

Salvador Dali’s “Aphrodisiac Jacket,” 1936, is a refreshing take on seduction and sexual ambiguity, featuring both a men’s shirt collar and tie and a brassiere tucked inside the jacket. The shot glasses originally held peppermint schnapps and viewers were invited to take a sip. A brave move, as some of the glasses have spiders suspended in the green liquid. As I viewed this amusing piece, a young woman chewing gum approached, giving the experience a minty verisimilitude. Also on view here is Dali’s “Lobster Telephone,” 1938. In the original, a real lobster replaced the receiver, and eventually added another fragrance to the viewer’s all-too-interactive experience.

“Aphrodisiac Jacket,” 1936, by Salvador Dali

I’m grateful to the curator for broadening my notion of surrealism by including such exemplars of “international biomorphism” as Henry Moore, David Smith, Alexander Calder, Max Ernst, and Joan Miro. One look at Miro’s “Lunar Bird,” 1945, bronze, and you know where Jeff Koons got a lot of his inspiration.

“Lobster Telephone,” 1938 by Salvador Dali

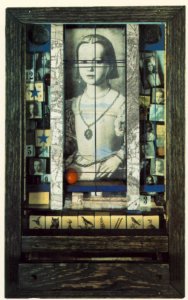

The American visionary, Joseph Cornell, is given an entire room to display his “Dream Worlds in a Box.” Cornell, while working with many of the same materials as his brethren (found objects, printed ephemera, marbles, feathers), avoided any hint of sex or violence, preferring to create charming assemblages that evoke childhood fantasy, as in “Medici Princess,” 1948-1952.

“Lunar Bird,” 1945, by Joan Miro

Providing “a darker view,” according to curator Fletcher, Isamu Noguchi is another artist whom I would not classify as a surrealist. Indeed, the Noguchi foundation’s website says the artist didn’t belong to any school or movement but “collaborated with artists working in a range of media.” Those artists include my beloved dance teacher, Erick Hawkins, for whom Noguchi designed beautiful stage sets. In any event, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Noguchi was incarcerated for seven months at an Arizona internment camp for Japanese-Americans. The foundation’s website tells us that he asked to be placed there as part of his activism on behalf of Nisei writers and artists.

“Medici Princess,” 1948-52, by Joseph Cornell

Of his experience at the camp, Noguchi wrote, “The memory of Arizona was like that of the moonscape of the mind…Not given the actual space of freedom, one makes its equivalent…where the imagination may roam to the further limits of possibilities, to the moon and beyond.” Made of cement, electric lights, cork, and string, “Lunar Landscape,” 1943-44, is his testament to the experience.

In a gallery called “Industrial Strength Surrealism,” I was thrilled to see Alexander Calder’s “Fish,” (metal, wood, painted metal, glass

“Lunar Landscape,” 1943-44, by Isamu Noguchi

and ceramic), 1944, an old friend featured in my novel, Still Life with Aftershocks. You’ll also see it in the banner on this website. In this show, the piece is hung at eye level. Denizens of DC are used to seeing “Fish” float above them in the Calder room in the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, now closed for renovation.

“Fish,” 1944, by Alexander Calder

Forged from farm implements and scrap metal, David Smith’s “Agricola 1,” steel and paint, 1951-52, is perhaps a better example of industrial art. This sculpture, with its bold and forthright abstraction, has a spirited presence. Once again, this admired artist would not fit my formerly narrow idea of a surrealist. No matter – I appreciated the more inclusive vision of the curator.

“Agricola 1,” 1951-52, by David Smith

And I hope you, dear reader, have enjoyed this glimpse – especially if you don’t get to see the show before it closes February 15, 2016.

Visit this jewel box of a museum to clear your mind and spirit while feasting on one of the world’s most stunning collections of 19th and 20th century paintings, sculpture and African and Asian art. The private collection of Carmen and David Kreeger is housed in a 1967 Phillip Johnson home, a work of art in itself, with its Byzantine domes, travertine limestone clad walls, and interior courtyard filled with towering tropical plants.

Visit this jewel box of a museum to clear your mind and spirit while feasting on one of the world’s most stunning collections of 19th and 20th century paintings, sculpture and African and Asian art. The private collection of Carmen and David Kreeger is housed in a 1967 Phillip Johnson home, a work of art in itself, with its Byzantine domes, travertine limestone clad walls, and interior courtyard filled with towering tropical plants. After passing through the grand salon (Picassos to the right of you, Braques to the left of you!), you’ll come to a magnificent stairway, its railing clad in molten bronze grill work. Each of the rectangles and parallelograms is a work of art, no two alike, like links in an enormous necklace. Please touch! Descend the staircase, passing a Calder mobile, to the lower gallery. Here you’ll enjoy Yves Tanguy, Man Ray, Jean Dubuffet, Frank Stella, among others. Knockouts include Sam Gilliam’s vibrant “Cape” (1969), and Gene Davis’ candy striped canvas, untitled, so you can make up your own (1953).

After passing through the grand salon (Picassos to the right of you, Braques to the left of you!), you’ll come to a magnificent stairway, its railing clad in molten bronze grill work. Each of the rectangles and parallelograms is a work of art, no two alike, like links in an enormous necklace. Please touch! Descend the staircase, passing a Calder mobile, to the lower gallery. Here you’ll enjoy Yves Tanguy, Man Ray, Jean Dubuffet, Frank Stella, among others. Knockouts include Sam Gilliam’s vibrant “Cape” (1969), and Gene Davis’ candy striped canvas, untitled, so you can make up your own (1953). backsides. Both are lovely.

backsides. Both are lovely.