“Composition in Green,” by Werner Drewes, 1935

Entering this ambitious exhibition, I immediately headed for the third floor where I knew I’d find artists at the heart of this modern collection: Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, John Marin, and Mark Rothko. It’s not that I didn’t want to see the earlier years, it’s just that I knew the third floor would likely take the entire time I had–it did. And it was enthralling. As the artist Kenneth Noland put it when he was living in Washington, DC in the fifties, “Going to the Phillips is like going to church.” Amen.

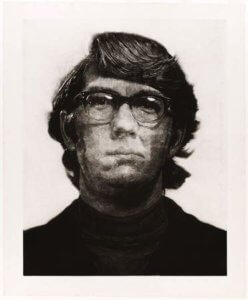

“Blue Still Life,” by John Graham, 1931

This show, which takes up the entirety of the newer wing (showcasing more than 160 works by 120 artists) , represents the return of paintings and sculptures that have been travelling since 2010, both around the world (Madrid, Tokyo) and in the United States (Nashville, Ft. Worth, Tampa). It’s astonishing how many of the works seen here were first shown in a museum by Duncan Phillips, the Collection’s visionary founder—he began the collection in 1921 as the nation’s first museum to be entirely devoted to modern art.

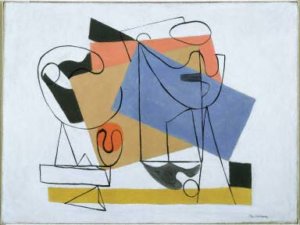

“Maritime,” by Karl Knaths, 1931

The first room, “The Legacy of Cubism,” gives us a purely American version in John Marin and Karl Knaths, who drew inspiration from nature; Stuart Davis and John Graham, who were influenced by Picasso’s exploration of objects for their own sake; and George GK Morris and Ilya Bolotowsky, who were pure abstractionists.

Shame on me, an ardent Phillips fan, for not knowing many of these artists well, if at all. If you’re like me, this show is a revelation with many “new” artists to enjoy. Among them, Werner Drewes, who was one of the 39 founding members of Abstract American Artists, and who studied with Kandinsky at the Bauhaus—you can see the influence in “Composition in Green,” 1935. Tucked in a corner by the elevator, this small painting literally grabbed me as I walked in. What energy, color and life!

“Abstraction, 1940,” 1940, by Ilya Bolotowsky

John Graham, a Russian born in Kiev who studied with John Sloan at the Art Students League, was also unfamiliar. Phillips was his first patron and admired Graham’s adaptation of Picasso’s use of heavy outlining in “Blue Still Life,” 1931. Despite its rather formal approach, there is something mysterious hidden in those shapes, and something satisfying about the way the artist resolves the composition.

While I’m confessing my art ignorance, let’s move on to Karl Knaths, whose large Provincetown-inspired painting, “Maritime,” 1931, was another discovery. The excellent notes accompanying the painting tells us that Knaths was influenced by Stuart Davis. He went on to influence many Washington artists himself, teaching for years at the Phillips Collection.

“Still Life with Saw,” 1930, by Stuart Davis

Also new to me was Ilya Bolotowsky, another founder of the American Abstract Artists. His “Abstraction 1940,” 1940, echoes Miro in its charming biomorphism.

The stand-out work in the room entitled “Still Life Variations” is Stuart Davis’ “Still Life with Saw,” 1930. During his1928 year in Paris, Davis fell under the sway of the surrealists. This painting, with its recognizable yet flattened objects floating in space, may have had surrealist origins, but it’s all his own.

“Red Polygons,” by Alexander Calder, 1950

“Degrees of Abstraction,” the third room, offers up this intriguing quote from Alexander Calder: “I think I am a realist. . . I make what I see. It’s only the problem of seeing it . . . the universe is real, but you can’t see it. You have to imagine it. Once you imagine it, you can be realistic about reproducing it.”

A mobile, “Red Polygons,” 1950, an untitled stabile, 1948, and a stand-alone sculpture, “Hollow Egg,” 1939, are all lit to great advantage, with fanciful shadows moving on the white gallery walls.

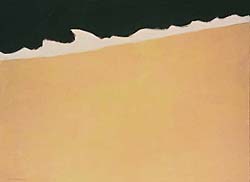

“Black Sea,” by Milton Avery, 1959

I’m not a Milton Avery fan, but was struck by the dramatic “Black Sea,” 1959, which was influenced by his friendships with Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottleib, both of whom are present in this show.

“Rose and Locust Stump,” by Arthur Dove, 1943

Arthur Dove, we learn, works “at the point where abstraction and reality meet.” How beautifully they meet in “Rose and Locust Stump,” 1943. This is the one I would steal and take home, given the chance.

Morris Graves gives us the luminous “Chalice,” 1941, gouache, chalk, and sumi ink on paper. This brooding piece finds an echo across the gallery in “Full Moon,” 1948, by Thedoros Stamos. Seeing reverberations in this painting of the work of Arthur Dove and Albert Pinkham Ryder, we learn that Phillips often paired this piece with Arthur Dove in the gallery.

“Chalice,” by Morris Graves, 1941

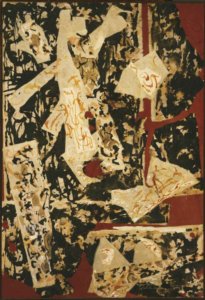

Acquired two years after the artist’s death, Jackson Pollack’s “Collage and Oil,” 1951, appealed to Phillips for its Asian aesthetic. Full of movement and intensity typical of this artist, it reads as a scroll.

“Collage and Oil,” by Jackson Pollock, 1951

Another stop-you-in-your tracks piece, Kenneth Noland’s “Inside,” 1950, was the first to be shown in a museum. One is struck by the thought: what if Duncan Phillips had not taken up Noland, or the many other “unknowns” of the day? We’d be so much the poorer.

“Interior View of Ocean,” 1957, by Richard Diebenkorn, was the first by the artist to be acquired by the Phillips Collection. Duncan Phillips was introduced to the California artist by his nephew, Gifford Phillips, Diebenkorn’s primary patron. Paired with the evocative, “Girl with Plant,” 1960, both paintings are good examples of Diebenkorn’s Matisse-influenced figurative period. (See my blog post, “In Love with Diebenkorn, the Berkeley Years.”)

“Inside,” by Kenneth Noland, 1950

In the room labeled “Abstract Expressionism,” Adolph Gottleib’s “The Seer,” 1950, stands out. With all the whimsy of Paul Klee, this large work appears to point the way to Jasper Johns’ fascination with targets and arrows.

“Interior View of Ocean,” 1957, by Richard Diebenkorn

Bradley Walker Tomlin (another artist new to me) gives us a breath of spring air (which we all need right about now) in his “No. 8,” 1952, one of his “petal paintings,” in charcoal and oil on canvas. Nearby is Kenzo Okada’s “Footsteps,” 1954—a Japanese rock garden in the fog. Both lyrical paintings evoke the subtle Asian sensibility that Phillips often sought.

“The Seer,” by Adolph Gottlieb, 1950

The final small room gives us these treasures: Sam Francis’ “Blue,” 1958, Morris Lewis’ “Number 182,” 1961, and a late Rothko on paper, “Untitled,” 1968.

“No. 8,” by Bradley Walker Tomlin, 1952

As you have gathered, this one floor of this massive show has so much important art, it could well stand on its own. Stay tuned for floors one and two—or better yet, meet me there and we’ll enjoy it together!

“Made in America” is on view until August 31, 2014.

http://www.phillipscollection.org/exhibitions/index.aspx