Bouquet of Concaves, by David Smith

All my life, art museums have been refuges, places to peer into the faces of long dead men, women, and children, to inspect the clothing worn in the 16th century, to be pulled into the vortex of a Pollack paint storm, to feel the power of ancient African sculpture, so fresh and modern in its lines. And when I come away from a particularly inspiring show, blinking into the sunlight, the whole world looks different.

Fittingly, the Phillips Collection’s centennial show is titled “Seeing Differently: the Phillips Collects for a New Century.” In 1921, Duncan and Marjorie Phillips opened their Washington, DC home and their art collection to the public, thus establishing America’s first museum devoted to modern art. The gallery was to serve as a memorial to his father and, poignantly, to his brother, James, who died in the 1918 influenza epidemic.

No 9, by Bradley Walker Tomlin

I’ve been to the show twice (it’s up through September 12, so you still have time to go). What struck me most each time were the vibrant new acquisitions by artists I knew little about. But as I started out in the addition to the gracious old brownstone house, a couple of old favorites snagged me anew.

Perched in an alcove as you walk down the steps into the main first floor gallery is David Smith’s painted steel sculpture, “Bouquet of Concaves,” 1959. This small sculpture has always appealed to me, with its hieroglyphic-like shapes which can be read either right to left or left to right. Somehow all the shapes are perfectly aligned, as if they organized themselves in such a way as to find utmost comfort. So, it was no surprise to learn that this piece was the first Smith made without preliminary drawings, simply laying the pieces out on a sheet of white paper on the floor and coming back to them day after day, moving one here, one there, until the pieces “found the arrangement.” During his collecting lifetime, Duncan Phillips very much wanted to acquire a Smith sculpture, but never bought one due to the high prices they commanded in the ’sixties. In 2008, forty-two years after his uncle’s death, Phillips’ nephew, Gifford, and his wife Joann Phillips, gave this sculpture to the collection.

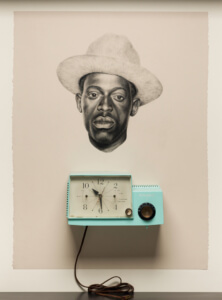

Kin XXXV (Glory in the Flower), by Whitfield Lovell

Another long-time favorite is Bradley Walker Tomlin’s 1952 painting, “No. 9,” also in the first-floor gallery. I love the pairing of the Smith sculpture and this painting. Both are so graphic and each has an Asian quality, speaking of balance and order, possibly achieved, in the Tomlin work, by a linear grid in which the pale brush strokes float to the foreground. So full of life and dancing spontaneity, this piece was painted only a year before Tomlin’s death. The work also hearkens back to his long friendship with Adolph Gottlieb who, thankfully, encouraged him to move away from Cubism to a looser, more gestural abstraction, perhaps allowing the shapes to find their perfect arrangement in much the way Smith did.

Entering the second-floor gallery, one of the newer acquisitions (2016) drew me in immediately: a striking conte crayon drawing, “Kin XXXV (Glory in the Flower),” by Whitfield Lovell, 2011. Every pore is visible in this skillfully rendered portrait, while the pairing of the man’s face and the clock radio causes a conversation to take place between them. The man’s hat appears to be from a bygone era, the radio certainly is. The passage of time is evident in the two faces: the man’s is black, with a sheen that seems to come from within. The clock’s face is white, featureless, blank, save for the stark black numbers. Time has taken its toll on the man – what he’s seen, what’s happened to him, the joys and the sorrows seem to have left him hollowed out. The radio, on the other hand, is plastic, pristine. We hear stories and music on the radio, canned, packaged and transmitted to us over the airwaves, but now, the radio is mounted with the man, and both are forever silent.

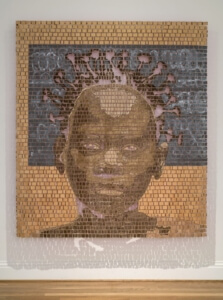

Maman Calcule, by Aime Mpane

What is Lovell saying about the communion between the man and the object? In search of answers, I found a Washington Post review of an earlier Phillips Collection show of Lovell’s “Kin” series. Over the years, this MacArthur grant winner accumulated a trove of old daguerreotypes, photos, and postcards from the early 1900s to the 1960s. From these long-gone faces he draws inspiration for his hyper-realistic, deeply sensitive portraits. One day, he says, he picked up an object, a “bust,” and held it next to one of his drawings. The object seemed to bring the drawing to life. Since then, he’s paired drawings with inanimate objects to create a back-and-forth dimension, all paying tribute to people who have never before been memorialized. Click her for the full review: https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/an-artist-refashions-the-past-whitfield-lovells-kin

A final question: what about the title, “Glory in the Flower”? The line comes from the Wordsworth poem Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood:

“Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of splendor in the grass, of glory in the flower;

We will grieve not, rather find

Strength in what remains behind…”

On the Way to the Cemetery (Tixan), Ecuador, by Flor Garduno

Entering the next gallery, another arresting face will greet you: “Maman Calcule,” 2013, by the Congolese artist Aimé Mpane. This large mosaic-like work is created from more than 1,000 pieces of painted plywood, the backs of which are painted red, so the shadows on the wall behind it glow. In this portrait, I see a golden child with worldly eyes who appears to stand before a blackboard. Does “calculation” here imply the working of sums on a blackboard? Is mama figuring out how to get her child prepared for adult life? In a Phillips Talks video, the artist discusses his notion of restoration—of what was lost to colonial legacy—while honoring the Congolese women who somehow keep the country going. “How the women do it, I don’t know,” he says, pointing out that the black and white image in the background represents the “western world who came in to crush and destroy.” View the video here:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1ziolvqLgI&t=6s

Similarly affecting is the small photograph by Mexican artist, Flor Garduño, “On the Way to the Cemetery (Tixan), Ecuador,” 1988. Three figures, one carrying a shovel, one with a tiny coffin on his back, walk over the chevron path toward a faint, fog-shrouded figure in the distance. This devastating image is infused with a timeless, dreamlike quality. In search of more information about Garduño, I found an excellent article on Artsy by Jacqui Palumbo. With many more images of the artist’s work, from beautiful nudes to “comic accidents,” all are infused with “tradition, myth, mysticism and the occult,” the article is worth a read: https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-photographer-flor-gardunos-sensual-dreamlike-portraits

Purple Antelope Space Squeeze, by Sam Gilliam

And finally, one more delight: Sam Gilliam’s exuberant 1987 work, “Purple Antelope Space Squeeze.” I always associate Gilliam with the Phillips, as this was one of his art refuges after he moved to Washington in 1962. Eventually, his work became known to Marjorie Phillips who, after Duncan’s death, offered Gilliam his first one-man show in 1966. For this piece, the artist worked with Tandem Press, sending sketches of the shaped paper he wanted for the final collage. The printing was done on carved woodblocks and the artist added embellishment using found objects and etched plates. Each impression is unique, as the artist placed and inked the various elements differently each for each printing.

Wow, is all I can say. I love the mischief of the two opposing triangle cut-outs, the off-kilter frame, and the horizontal slash of negative space between the two parts. It feels like a dance, the way all the elements play together. Up close, its depth is dizzyingly three-dimensional.

After lingering with “Purple Antelope” for a time, I continued further into the old house to savor those Bonnards, and Braques, and Doves, and all the other gems that have inspired Sam Gilliam and me, and countless others, over the decades.

https://www.phillipscollection.org/event/2021-03-06-seeing-differently