Every time I see the Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company perform, I wish I could watch each dance over and over again.

The Company Rehearsing

On Saturday, my wish came true.

My friend Jeanne and I were privileged to observe a rehearsal for the up-coming DTSBDC show, “Portraits.” This June 15th and 16th performance at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater will celebrate the company’s 25th year of delighting audiences as Washington, DC’s preeminent dance company.

The first dance rehearsed was “Confluence,” reviewed in this space on April 19, 2014 when it premiered in the magnificent Kogod Courtyard at the National Portrait Gallery. http://ellenkwatnoski.com/premier-confluence-dana-tae-soon-burgess-at-the-national-portrait-gallery-april-19-2014/

Even though this was a rehearsal, with stops and breaks for Burgess’s and Katia Chupashko Norri’s (associate rehearsal director), inventive notes to the dancers, this piece still took our breath away. Choreographer Burgess was inspired by the moody 1938 portrait of modern dance pioneer Doris Humphrey by Barbara Morgan. The portrait was part of the Smithsonian Portrait Gallery’s show, “Dance the Dream,” which featured portraits of legendary dancers, Burgess himself among them.

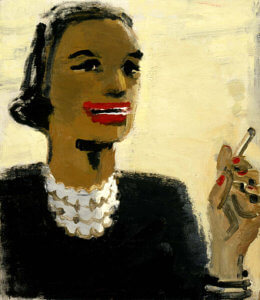

Doris Humphrey, by Barbara Morgan, 1938

Fraught with psychological overtones, this dance expresses “an emotional terrain of the mind”—in Burgess’s words—the uncomfortable state brought about by short meetings—trysts—in which unresolved feelings abound.

The dancers became lit from within as they got into character—even though still working out spacing, timing, and minute changes in hand gestures, arm shapes, and where the dancer’s eyes should be focused. These and many other adjustments will ultimately combine to form the intention, emotional content, and musicality of the final performance. We were struck by Burgess’s and Norri’s precise and sometimes amusing notes to the dancers: “After the contact lens moment,” (a dancer plucks something invisible from the floor), “The music is pulling you in,” “Picture lasers in your arms carving the space into a figure eight.”

From the 2014 National Portrait Gallery Premier

The music for this piece is haunting. Ernest Bloch’s “Hebraic Suite” pumps up the emotional content, building tension as the dancers lift each other, fleetingly touch, curl to the ground, and pepper their lyrical movements with highly original hand gestures: pecking, stabbing, caressing, striking, and swooping in crane-like arches.

From the Premier

Next, the company worked on “I Am Vertical,” a dance inspired by Sylvia Plath’s poem of the same name. Again, as the first-ever resident choreographer at the National Portrait Gallery, Burgess took his inspiration from a small but devastating NPG show of Plath’s art and writing. The dance opens with several couples dancing a spirited lindy hop to “Take the A Train.” When the music morphs into a surreal warp, a disembodied voice begins to read Plath’s poem: “I am Vertical…But I would rather be horizontal.” The dance plays with planes – upright and utterly still lying down. Following the poem’s haunting ending, “I shall be useful when I lie down finally,” we hear Plath interviewed about her fateful meeting with fellow poet and husband-to-be Ted Hughes. The role of Plath is danced by Sarah Halzack, with three other women dancers appearing as muses or influences on the poet; they change roles now and then, with each seated, miming typing on an invisible typewriter.

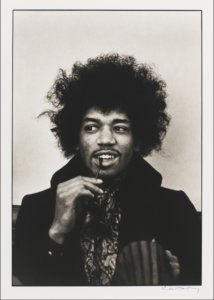

Sylvia Plath 1932 – 1963

Again, the dancing is sublime, the choreography original, and the emotional content utterly riveting.

After the rehearsal when the associate artistic director Kelly Moss Southall began literally to roll up the floor, we chatted briefly with Dana regarding the Plath piece. Jeanne, my friend, is a dance lover and a poet herself. Dana told us a bit about his process in creating a dance, how each dancer has her or his own motivations, inner desires, and character arc, and that each section of the dance corresponds to a chapter in a book, or an act in a play.

Once again, we could have watched for hours – and luckily, we will all get the chance to see these gem-like pieces—among others—performed at the Kennedy Center on Friday, June 15th and Saturday, June 16th at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater, 7:30PM. Tickets are on sale now!

http://www.kennedy-center.org/calendar/event/RSXAL

I hope to see you at this much-anticipated event in celebration of the Dana Tai Soon Burgess Dance Company’s 25th year. We are fortunate indeed to have this stellar dance company performing in Washington, DC, but, in the words of the Washington Post’s dance critic, Sara Kaufman, “This artist is not only a Washington prize, but a national dance treasure.”

I am Vertical

by Sylvia Plath

But I would rather be horizontal.

I am not a tree with my root in the soil

Sucking up minerals and motherly love

So that each March I may gleam into leaf,

Nor am I the beauty of a garden bed

Attracting my share of Ahs and spectacularly painted,

Unknowing I must soon unpetal.

Compared with me, a tree is immortal

And a flower-head not tall, but more startling,

And I want the one’s longevity and the other’s daring.

Tonight, in the infinitesimal light of the stars,

The trees and the flowers have been strewing their cool odors.

I walk among them, but none of them are noticing.

Sometimes I think that when I am sleeping

I must most perfectly resemble them —

Thoughts gone dim.

It is more natural to me, lying down.

Then the sky and I are in open conversation,

And I shall be useful when I lie down finally:

Then the trees may touch me for once, and the flowers have time for me.

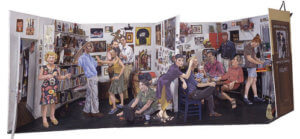

Star of the show may well be “Loft on 26th Street,” by pop art trickster Red Grooms (plywood, cardboard, paper and wire), 1966-7. This delightful piece shows us the studio apartment of Mimi and Red Grooms, “Home of Ruckus Films,” and its denizens partying up a storm. Grooms himself is slicing potatoes at the right of the diorama. Endless wonderful things to look at here: the art lining the walls, the detailed clothing, the contents of the fridge, even a recognizable china pattern my friend Pat had when we were living in New York’s lower East Side.

Star of the show may well be “Loft on 26th Street,” by pop art trickster Red Grooms (plywood, cardboard, paper and wire), 1966-7. This delightful piece shows us the studio apartment of Mimi and Red Grooms, “Home of Ruckus Films,” and its denizens partying up a storm. Grooms himself is slicing potatoes at the right of the diorama. Endless wonderful things to look at here: the art lining the walls, the detailed clothing, the contents of the fridge, even a recognizable china pattern my friend Pat had when we were living in New York’s lower East Side.