“Hemlock,” 1956

Up until this summer, I’d seen only one or two of Joan Mitchell’s paintings and they were always hung with other painters’ work. Thanks to my friend, Bonnie, who invited me to join her at the Mitchell retrospective at the Baltimore Museum of Art, I might not have found an artist who has become an inspiration in my life – not that I’m flinging paint at canvas, although it’s tempting. I’m trying, in a quieter, smaller way, to find my own version of her path, which combined a deep immersion in nature, music, and poetry, and resulted in some of the most exuberant, courageous, and original art I’ve ever experienced.

Digital versions of Mitchell’s monumental paintings will only give you a suggestion of the real thing, like a baseball card compared to a living, breathing athlete in action. But it’s what we have, so here goes.

This stunning retrospective (co-curated by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the BMA) is organized chronologically, so we see Mitchell’s early art in the first room. Born in 1925 to a wealthy and cultured Chicago family, young Joan studied (as my father did a decade or so before her) at the Art Institute. Several of these early works are breathtaking: “To the Harbor Master” (1957) and “The Bridge” (1956; the first of her many diptychs) among them, but the one that stopped me in my tracks was “Hemlock,” (1956). I hadn’t looked at the wall plaque, so didn’t know the title immediately, but instantly felt its stately tree-essence. The crisp, fragrant boughs (somehow the painting seemed to give off a wintry, evergreen scent) are set off by a snowy white field, the sweeping branches speckled with blue, orange, and crimson, like flashes of birds pecking at the tree’s base.

The title comes from a Wallace Stevens poem, “Domination of Black.”

“Out of the window, / I saw how the planets gathered / Like the leaves themselves / Turning in the wind. / I saw how the night came, / Came striding like the color of the / heavy hemlocks. . .”

At that point, I was hooked.

“Untitled,” 1961

In the second room, I was equally floored by “Untitled,” (c. 1961). Nearby hangs a photo of Mitchell in her Paris loft—by now, she was splitting her time between New York and Paris. In New York she’d become a known artist in the emerging abstract expressionist vein, including Elaine de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, and Lee Krasner, among others. The scene in New York was intense, and increasingly, Mitchell sought the relative obscurity of Paris where she felt comfortable following her own muses. “Untitled” is like the flip side of “Hemlock.” The brooding green/black is gone, exploding in Easter egg color, as if the artist said, “Oh, what the hell,” as she squirted magenta directly from the tube onto the canvas. This bloom of color seems to emerge from a muddy ground of splotches, drips and fishtails of paint. Mitchell appears to revel in improvising with the paint: making flicks, swirls, dabs. The black blob rescues the lilac from a too-pretty realm, giving it heft and balance. I was soon lost in the ravishing tangle at the left, marveling at the artist’s freedom with the splotchy slaps of turquoise, crimson, ochre, white, plum, and jade. Experiencing this painting results in an upwelling of feeling as one’s sightline is drawn up to a pale sky.

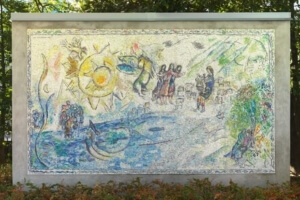

“Sans Neige,” 1969

As you enter the next room, you’re greeted by an enormous triptych, “Sans Neige,” 1969, painted after Mitchell had moved from Paris to La Tour, her estate along the Seine in Vétheuil, France. Coincidentally, or perhaps by design, Monet, one of the painters she most admired, lived and painted in a cottage on the very same estate. The curators at the San Francisco Museum of Art speculate that the title, “Without Snow” in English, could be a “sly reference to Monet’s well-known paintings of Vétheuil in winter…” Unlike “Hemlock” and “Untitled” which evoke the majesty and exuberance of nature, this work plunges the viewer into a bustle of human life. It’s a show-stopper, a brilliant carnival whirl of crowds, activity, the swirling life of cafes, whipping flags, even animal tracks, weaving among the grounding rectangles of crimson and blue. It’s irresistible, joyous, and celebratory of human life.

In the next gallery, a video shows Mitchell welcoming an interviewer into her La Tour studio. The two women sit on a bench by the window and gaze out at the magnificent view of fields, the town, and the river. The interviewer says something like, “How wonderful it must be to look out this window and paint.” Michell replies, gesturing at the view, “Oh, I could never even try to paint that…” Rather, she says, she closes the shutters to paint, preferring to conjure memories of times, places, people, and nature, carrying her landscapes with her.

“No Birds,” 1987

We can’t know why there are no birds in “No Birds” (1987-88), even if we can guess why there’s no snow in “Sans Neige,” but Mitchell’s intent to pay homage to Van Gogh’s “Wheatfield with Crows” (1890), is clear. Made late in Mitchell’s life when, diagnosed with cancer, she was often in pain, this startling work seems to reveal that she, with her typical courage and honesty, is facing her mortality. It’s as if the absent crows have left black contrails in Mitchell’s painting, and Van Gogh’s vivid blue sky is now a crouching pool at the far left. But the bright yellow field is vibrant, the wheat stalks burst forth from the horizontal ground, and the turbulent movement speaks to me more of life than death.

“Wheatfield with Crows,” by Vincent Van Gogh, 1890

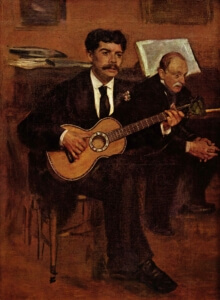

At La Tour, Mitchell spent many hours with her artist friends, among them composer Gisèle Barreau. The two spent countless hours listening to music and playing it together. “Two Pianos,” 1980, is named for a Barreau composition, also 1980. I looked it up on YouTube, but found only this video of a performance of “Blue Rain,” 1998, for two pianos and percussion. You can listen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrrXz6ZOWLE.

“Blue Rain” was composed six years after Mitchell’s way-too-early-death at 67. Listening to Barreau’s music, though, I can picture the two women playing together, perhaps with Mitchell’s beloved dogs at their feet. It’s tempting to see two different personalities in the two sides of the diptych, one spare, pale, and diffident, the other dense, rich, passionate, and persistent. Of course, one can also “see” the music dancing before your eyes and revel in the back and forth between the “two pianos.”

“Two Pianos,” 1980

In addition to these and many more wonderful paintings, the show offers a trove of ephemera: sketch books, correspondence, photographs, the video shot at Vétheuil, and one of Mitchell and friends sailing in the Mediterranean. Some small works balance the monumental ones, too, especially a wall of ravishing pastels made directly on paper with typewritten poetry by friends.

What a rich and impressive life, and what a rich and moving show.

The Joan Mitchell retrospective at BMA is up until August 14, 2022. If you possibly can, do try to see it.

https://artbma.org/exhibition/joan-mitchell

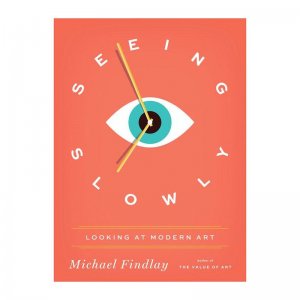

So, off I went again to the Mall, first stopping to sit on a bench, close my eyes, and breathe deeply for several minutes. (Step One in the Findlay method.) Next, I tried to let the art pick me (Step Two), rather than looking around for something “important,” or a piece by a well-known artist.

So, off I went again to the Mall, first stopping to sit on a bench, close my eyes, and breathe deeply for several minutes. (Step One in the Findlay method.) Next, I tried to let the art pick me (Step Two), rather than looking around for something “important,” or a piece by a well-known artist. At first, I saw only the enormous red-orange I-beams arranged at various angles, with one V-shaped piece dangling by a cable. As I gazed, words began to float up in my mind: forthright, masculine, audacious, thrusting, grounded. But that V. That V was oddly touching, hanging out there at the mercy of the wind, moving and changing as it turned. I noticed several other Vs in the composition and, as the light changed, the sculpture began to look like an enormous drawing.

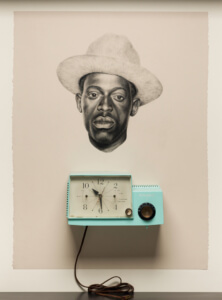

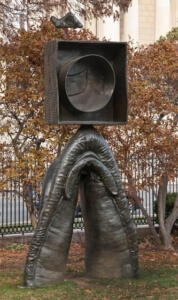

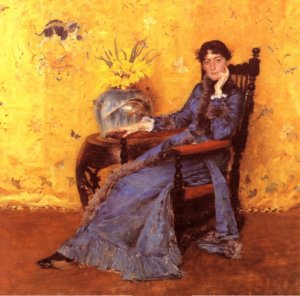

At first, I saw only the enormous red-orange I-beams arranged at various angles, with one V-shaped piece dangling by a cable. As I gazed, words began to float up in my mind: forthright, masculine, audacious, thrusting, grounded. But that V. That V was oddly touching, hanging out there at the mercy of the wind, moving and changing as it turned. I noticed several other Vs in the composition and, as the light changed, the sculpture began to look like an enormous drawing. I circled the sculpture, all burnished and gleaming in the late-morning sun, I wasn’t sure how I felt about him. After about three minutes, a creepy sizzle from his eyes gave me the sense he was watching me. As I moved, his eyes followed. He seemed to say, with a leer, You have no idea who I am or where I came from, do you, honey? I shuddered. No epiphany with this guy, no communion, no awe.

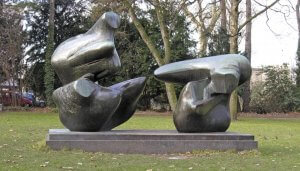

I circled the sculpture, all burnished and gleaming in the late-morning sun, I wasn’t sure how I felt about him. After about three minutes, a creepy sizzle from his eyes gave me the sense he was watching me. As I moved, his eyes followed. He seemed to say, with a leer, You have no idea who I am or where I came from, do you, honey? I shuddered. No epiphany with this guy, no communion, no awe. I was relieved to move on and soon came upon two large shapes on a pedestal. Dappled under trees, this piece of abstract art sits overlooking the brooding Rodins in the Hirshhorn’s sunken sculpture garden.

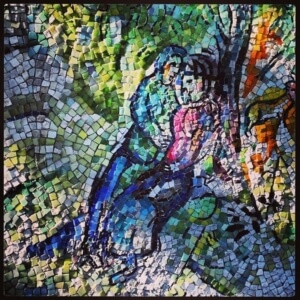

I was relieved to move on and soon came upon two large shapes on a pedestal. Dappled under trees, this piece of abstract art sits overlooking the brooding Rodins in the Hirshhorn’s sunken sculpture garden. After three minutes of circling, I returned to the front of the sculpture. As I watched, the space between the figures began to vibrate and I swear I saw them move toward each other. The energy charge between the two creatures was electric. As I circled the sculpture again, it struck me that those shapes could never have taken any other shape that the ones they’d become. Broad and comforting, maybe male and female, maybe not, the pull they exerted on one another was palpable.

After three minutes of circling, I returned to the front of the sculpture. As I watched, the space between the figures began to vibrate and I swear I saw them move toward each other. The energy charge between the two creatures was electric. As I circled the sculpture again, it struck me that those shapes could never have taken any other shape that the ones they’d become. Broad and comforting, maybe male and female, maybe not, the pull they exerted on one another was palpable. So there you have my experiment in seeing slowly. I highly recommend trying it with the public art where you live. Fortunately for me, Washington, DC is blessed with a large quantity of outdoor art, and as I get more and more hooked on sculpture, I’ll return to this space with more slow observations.

So there you have my experiment in seeing slowly. I highly recommend trying it with the public art where you live. Fortunately for me, Washington, DC is blessed with a large quantity of outdoor art, and as I get more and more hooked on sculpture, I’ll return to this space with more slow observations.

The front view doesn’t enable one to foresee the back view. As you move round it, the two parts overlap or they open up and there’s space between. Sculpture is like a journey. You have a different view as you return. The three-dimensional world is full of surprises in a way that a two-dimensional world could never be.”

The front view doesn’t enable one to foresee the back view. As you move round it, the two parts overlap or they open up and there’s space between. Sculpture is like a journey. You have a different view as you return. The three-dimensional world is full of surprises in a way that a two-dimensional world could never be.”

A larger painting, “Ocean Park,” 1960-61, evokes the series of the same name made by Richard Diebenkorn. Irwin’s vision of the California community where both artists drew inspiration is more kinetic that Diebenkorn’s calmer vision. Lines fly as if hurled by some paint-wielding Thor. Is that a jet plane about to land? Cars streaming by? Tides surging, lawn chairs in a jumble? Loved it. Then I read that this was one of the “pick-up sticks” paintings in which Irwin wanted to expel any visual associations with the real world. Oops.

A larger painting, “Ocean Park,” 1960-61, evokes the series of the same name made by Richard Diebenkorn. Irwin’s vision of the California community where both artists drew inspiration is more kinetic that Diebenkorn’s calmer vision. Lines fly as if hurled by some paint-wielding Thor. Is that a jet plane about to land? Cars streaming by? Tides surging, lawn chairs in a jumble? Loved it. Then I read that this was one of the “pick-up sticks” paintings in which Irwin wanted to expel any visual associations with the real world. Oops.