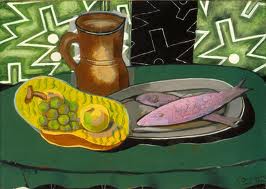

“Gardens at Daubigny,” by Vincent Van Gogh

…walk into a bar. Oops, never mind. That’s another blog for another time.

Seriously, though, if you walk into the Phillips Collection here in DC you’ll meet them all – and more. Gaugin to Picasso: Masterworks from Switzerland, now on view, showcases some 60 works from the Staechelin and Im Obersteg Collections, normally on view in the Kunstmuseum in Basel. Rudolf Staechelin and Karl Im Obersteg were contemporaries of Duncan Phillips, the founder if this, the first museum of modern art in the United States, and like him, collected widely in the mid-nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This vivid show is the first to bring selected works from these collections to America.

“Nafea faa ipoipo (When Will You Marry?),” by Paul Gaugin

Van Gogh’s “Gardens at Daubigny,” was painted in July, 1890, in the height of a glorious summer in Auvers, France. This is one of several paintings the artist made of Daubigny’s gardens, but the only one to feature a small black cat in the foreground. He wrote his brother Theo that it was “a picture I’ve had in my mind ever since I came here.” Tragically, Van Gogh took his life on July 29, 1890. Current thinking suggests that Van Gogh may have been bi-polar, with periods of frenzied painting and writing–Van Gogh wrote 800 letters in his lifetime–followed by periods of deep depression. That he could paint these gardens with such joy and take his own life shortly thereafter gives this swirling, wiggling image a kind of awful poignancy.

“Mont-Blanc with Pink Clouds,” by Ferdinand Hodler

The magnificent, “Nafea Faa Ipoipo (When Will You Marry?),” 1892, was painted during Paul Gaugin’s first stint in Tahiti. This enigmatic image of two Tahitian girls was recently sold to a private buyer, perhaps Qatari, according to a February 15, 2015 article in The New York Times. The selling price of $300 million was neither confirmed nor denied by a tight-lipped seller, none other than Rudolf Staechelin’s 62 year old grandson. News of the sale shocked Basel and sent some 7,500 people to the Kunstmuseum to see it before the gallery closed for renovation. The buyer, whoever he or she is, will take possession in January 2016. The present day Staechelin said, “In a way it’s sad…but…private collections are like private persons. They don’t last forever.” So…we’re even luckier to see this work before it may disappear from view.

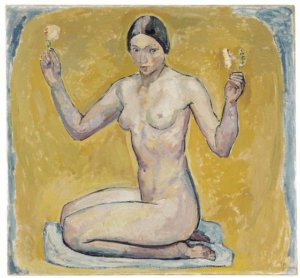

“Kneeling Nude on Yellow Ground,” by Cuno Amiet

I have mixed feelings about this artist. While I find Gaugin’s penchant for going native more than a little condescending, and his involvement with a thirteen-year-old Tahitian girl (with his wife and child at home in France) repugnant, this painting is breathtaking. As a colorist, Gaugin is a master. I love the interplay between the two figures, the curving, sensuous body of the girl in native dress, and the stiff, upright carriage of the one in Western dress. Both look away from the viewer, in different directions, while the figure behind holds up a portentous hand, like a figure in a religious allegory.

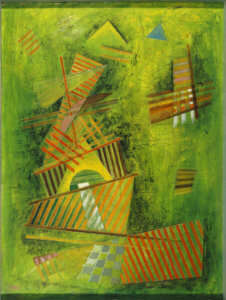

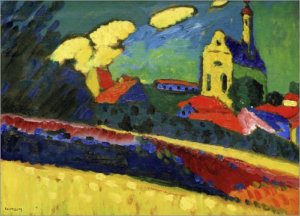

“Study of Murnau–Landscape with Church,” by Wassily Kandinsky

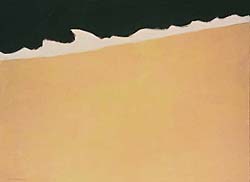

Another work still in the Staechelin collection is Ferdinand Holder’s “Mont Blanc with Pink Clouds,” 1918. The colors are so delicate yet so ravishing, the piece looks edible. It put me in mind of the paintings of Augustus Vincent Tack, who was an advisor to Duncan Phillips and whose art Phillips admired and collected. The iridescent, almost abstract image is flattened, yet seductively deep.

Speaking of ravishing: Swiss artist Cuno Amiet’s “Kneeling Nude on Yellow Ground,” 1913, is a knock-out. I love the quivering intensity of this girl’s body, her fixed gaze. It’s as if she’s intently waiting for her cue, maybe a cymbal crash, to leap up and take her place in the dance. She appears to be one of several nymphs in a frieze, perhaps representing spring.

Color, color, color! You could get drunk on the color in this show.

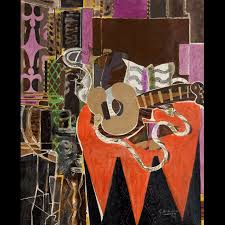

“The Frog,” by Suzanne Valadon

Kandinsky’s “Study of Murnau—Landscape with Church,” 1909 blew me away. I love the way the landscape seems to tumble off the canvas, the riotous color, the yellow clouds flying up into the sky. Even the building looks impermanent, as if about to explode.

The gem of the show for me is Suzanne Valadon’s “The Frog,” 1910, in pastel and oil on paper. Valadon—the only woman in the show—was an artist’s model in Montmartre, a fall from a trapeze having ended her career as a circus performer. She modeled for Puvis de Chavannes, Pierre-August Renoir, and Toulouse Lautrec, among others, who encouraged her to pursue a career as a painter. Seductive, independent, and headstrong, she lived outside bourgeois rules, giving birth at 18 to a son, the artist Maurice Utrillo. Here, her “frog,” about to climb into a bathtub, shows a more muted palette than many of the works in this show, but the vigorous outlining is there, as is the coiled energy of the model.

“Absinthe Drinker,” by Pablo Picasso

Picasso’s famous “Absinthe Drinker,” 1901, is displayed in the center of the gallery with a wonderful bonus painting on the reverse. Our drinker is bathed in color, but her eyes are dead, her face expressionless. The influence of Toulouse Lautrec and Gaugin are evident in the outlining and bold color. On the other side (Picasso was poor and canvas was in short supply) is a wild painting that was much more to my taste: “Woman at the Theater.” Isn’t she great? Here is a sophisticated Parisienne, whose gimlet eye misses nothing, nailing the viewer with a jaded expression as the theater crowd buzzes around her.

“Woman at the Theater,” by Pablo Picasso

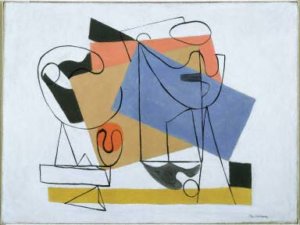

Thirty years later, Picasso would paint very differently, reducing “Sleeping Nude,” 1934, to a series of orbs and swooshes, her head thrown back dramatically. But color and outlining are still important to him and to these collectors whose mutual eye and taste can be seen in works that span decades. Many other wonderful artists are represented here—Modigliani, Cezanne, Utrillo (Suzanne Valadon’s son), Pissarro, Manet, and Chaim Soutine among them.

“Sleeping Nude,” by Pablo Picasso

The show will be up until January 10, 2016.

http://www.phillipscollection.org/events/2015-10-10-exhibition-staechelin-im-obersteg