“Lucky U,” 1960

The title of this show is taken from Robert Irwin’s words about his intention to move from traditional art—paint on canvas—to more “conditional” works that deal with light and space directly. At the Hirschhorn Museum in DC, this is the first historical survey of the California artist’s work from the late 1950s through today. Up until September 5, 2016—the Hirshhorn is the only venue—it’s a rare treat.

“Ocean Park,” 1960-61

Of the show, its curator, Evelyn Hankins said, “The historical portion of the exhibition includes many rarely seen works that, because of their extremely subtle nature, demand in-person viewing. And as both these objects and the new installation demonstrate, Irwin’s art becomes fully present only when you are standing in the physical space, experiencing it over an extended period of time.” Italics mine.

In the late 1950s Irwin created small works meant to be held by the viewer. Beautifully framed in wood, these small paintings hang on two walls and lie flat in a case in the middle of the gallery. They possess a tactile, restless energy that does invite touch. “Lucky U,” a little charmer made in 1960, was loaned from the collection of the artist, now 87.

A larger painting, “Ocean Park,” 1960-61, evokes the series of the same name made by Richard Diebenkorn. Irwin’s vision of the California community where both artists drew inspiration is more kinetic that Diebenkorn’s calmer vision. Lines fly as if hurled by some paint-wielding Thor. Is that a jet plane about to land? Cars streaming by? Tides surging, lawn chairs in a jumble? Loved it. Then I read that this was one of the “pick-up sticks” paintings in which Irwin wanted to expel any visual associations with the real world. Oops.

A larger painting, “Ocean Park,” 1960-61, evokes the series of the same name made by Richard Diebenkorn. Irwin’s vision of the California community where both artists drew inspiration is more kinetic that Diebenkorn’s calmer vision. Lines fly as if hurled by some paint-wielding Thor. Is that a jet plane about to land? Cars streaming by? Tides surging, lawn chairs in a jumble? Loved it. Then I read that this was one of the “pick-up sticks” paintings in which Irwin wanted to expel any visual associations with the real world. Oops.

From 1961 to 1964, Irwin made a series of “line” paintings in his desire to obliterate the “Rorschach effect” in which the eye makes associations with elements of nature or human figures. Or lawn chairs. In “Crazy Otto,” 1962, four heliotrope lines vibrate against a vivid background. One thinks first of Otto. Who was he? In what way was he crazy? And then, inevitably, of Rothko.

“Untitled,” 1963-65

The artist further challenged himself to make a painting without making a visible mark. This, our curator Hankins tells us, is the flex point in Irwin’s career. In the “dot paintings” he has made works that require an “active, persevering viewer.” True. It’s impossible to see these works in reproduction, or even standing back from them by the usual three or four feet. In “Untitled,” 1963-65, what looks like a uniform white ground is revealed to be gazillions of tiny dots in complementary colors that effectively cancel each other out.

In 1966 Irwin abandoned painting on canvas altogether and began working with auto body shops and industrial fabricators to create objects that test the “experiential and material limits of art.”

Acrylic Column, 1969 – 2011

Floor-to-ceiling acrylic columns, triangular in shape, and highly polished, refract light while doing very interesting things to the people who walk by them. Something about the simplicity of conception and the quality of execution of these columns made me think of Donald Judd’s work in mill aluminum. Just as I wondered if the artists knew one another, two photographers began to set up, each wearing T-shirts that read, “Robert Irwin Opening: Dawn to Dusk, 23 July, 2016, Marfa Texas.” They were absorbed in their work, and didn’t seem approachable, but a young woman who appeared to be with them said they were working on a documentary.

“Dawn to Dusk,” 2016, at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas

Later, Google filled me in. Yes, Judd and Irwin knew each other and Judd admired and collected Irwin’s work. Sixteen years in the planning, a new large-scale Irwin piece was installed this month in an old Army hospital at Judd’s Chinati Foundation in Marfa. For more on Donald Judd and Chinati, see my October, 2013 blog post.

http://ellenkwatnoski.com/road-trip-minimalism-to-the-max-in-marfa-tx/

Made in 1969, the “Untitled” disc had me and a group of young art campers enthralled. The painted aluminum disc gives off a pale yellow radiance that blushes at the edges. Again, the artist is playing with our perception of “art.” Shadow and light are as important to this ethereal piece as paint on aluminum.

Untitled Disc, 1966-67

Even more spell-binding is another of the untitled disc series, also made in 1969. Lit from above, the work is positively otherworldly. I expected it to speak, utter oracular wisdom, or some Hal-like pronouncement.

The Hirshhorn is a giant doughnut of a building, with the galleries along the outer rim and a ring of glass overlooking a fountain in the interior hole of the doughnut. When you walk from gallery to gallery, you’re aware of the circle you’re tracing, but at the same time, not.

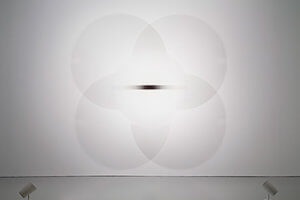

Untitled Disc, 1969

Entering “Squaring the Circle,” 2016, Irwin’s site-specific piece, you’re warned that your “perceptions will be challenged.” In the center of a wall is a doorway within a glowing white space. You feel pulled toward the door. Is it real? Can you walk through it without, like Alice, being plunged into some new reality? After a bit of exploration, you realize the curve of the gallery wall has flattened. In fact, the “wall” is a white gauze scrim stretched across the vast space so that it appears solid and the door appears to float inside the actual door to the outer rim of the doughnut.

“Squaring the Circle,” 2016

The show closes with a 1973 video of Irwin speaking about his art. I wasn’t able to find it on YouTube, but here’s a link to his fascinating talk at Stanford University in which both the Hirshhorn and Marfa installations are discussed.

You have to put up with a gassy introduction, but it’s worth it. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Ac-m3W9fGY

Said Hirshhorn Curator Evelyn Hankins, who organized the exhibition. “The historical portion of the exhibition includes many rarely seen works that, because of their extremely subtle nature, demand in-person viewing. And as both these objects and the new installation demonstrate, Irwin’s art becomes fully present only when you are standing in the physical space, experiencing it over an extended period of time.”

.