“Basket of Flowers on an Alabaster Pedestal,” 1785, by Gerard Van Spaendonck

The Virginia Museum of Fine Art’s exclusive East coast showing of Van Gogh, Manet, and Matisse: the Art of the Flower is touted as the first major American exhibition to examine 19th century French floral still life painting and its development into a modern, 20th century form. It’s an expansive, but not overwhelming show, featuring some 30 artists, including Eugene Delacroix, Gustave Courbet, and Henri Fantin-Latour, in addition to the stars given top billing.

“Bouquet of Lilies and Roses in a Basket on a Chiffonier,” 1814, by Antoine Berjon

We drove to Richmond to see the show during Virginia Garden Week, and on Earth Day to boot, so we were primed to bliss out over tulip, peony, ranunculus, and lily. Beautifully mounted, each gallery of this dazzling show is painted a different color— lavender, spring green, heliotrope—giving the sense that the rooms themselves are blooming as you walk through them.

“African Woman with Peonies,” 1870, by Frederic Bazille

The exhibit begins with the French masters whose technically brilliant work laid the foundation for the genre. Often these preeminent flower painters were originally Dutch or Belgian, trained in the highly realistic northern tradition of flower painting. Interestingly, their botanical illustrations also appeared in scientific journals of the day. Gerard van Spaendonck moved to Paris as a young man and rose to royal flower painter in the court of Louis XVI. In his “Basket of Flowers on an Alabaster Pedestal,” 1785, the work is so fine, it appears to be painted on porcelain. No brush strokes break the illusion that these flowers were moments before, plucked from some garden of perfection. In addition to admiring the flowers, we delighted in picking out ladybugs, butterflies, and other fauna, not to mention the occasional shimmering dewdrop.

“Asters in a Vase,” 1875, by Henri Fantin-Latour

The next room, “Flower Painting in Lyon,” brings us Antoine Berjon and his stunning “Bouquet of Lilies and Roses in a Basket on a Chiffonier,” 1814. We learn that Berjon was a professor of flower painting at Lyon’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts, founded by Napoleon to revive Lyon’s silk industry. Here, Berjon trained flower painters to supply images for the exacting process of silk printing. His mastery of both realism and a quirky sensibility are seen in this work, with the man-made objects and found natural objects included in the composition. It’s a tour de force of textural painting, no doubt intended to impress his patrons, but also to give the viewer a wider experience, moving away from more formal compositions in which the bouquet simply appears on a surface with no human intervention.

“Bouquet in a Loge,” 1878-80, by Auguste Renoir

In the room devoted to the romantic Delacroix and modern master Courbet, we were struck by the new looseness and freedom with which these artists approach their flowery subjects. A favorite in this group is “African Woman with Peonies,” 1870, by Frederic Bazille, a “friend and ally” of those who went on to form the Impressionist school. In this lovely painting, she who arranges the flowers is given a role of equal importance, if not greater, in the magnificence of the final arrangement.

“Lilacs in a Window,” 1880-83, by Mary Cassatt

With Henri Fantin-Latour, we entered yet another realm—now the brush strokes are still looser and far less slick. We were transfixed by “Asters in a Vase,” 1875. The fresh, round flower faces are echoed in the shape of the vase, creating a circular, very pleasing composition. Emile Zola was similarly drawn in, saying in 1880, “The canvasses of M. Fantin-Latour do not assault your eyes, do not leap at you from the walls. They must be looked at for a length of time in order to penetrate them, and their conscientiousness, their simple truth—you take these in entirely…”

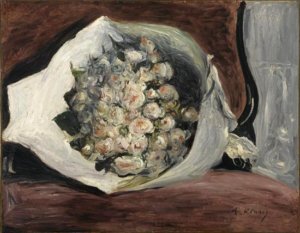

Moving into the realm of Degas and Renoir we passed through an ante-room where our fellow art lovers were invited to sit down and sketch a vase full of flowers. We were tempted, but time was short and Renoir pulled at us. In “Bouquet in a Loge,” 1878-80, Auguste Renoir takes his flowers out of the home and places them on a chair in a theater. Even though the chair is almost abstract, we sense that this is a public place. The roses, so dense and tightly-furled, have been discarded in a moment of enthusiasm with what’s happening on the stage, or a distraction from an admirer, or any number of other imagined scenes. The flowers are now part of a story and not merely displayed for their own sake.

“Daisies,” 1888, by Vincent Van Gogh

In a striking Mary Cassatt composition (hung in the room devoted to Manet and his influences), “Lilacs in a Window,” 1880-1883, the artist places the vase of lush flowers on a window sill, half in and half out of the house. The window, likely one in a greenhouse, serves to enclose the vase and creates a series of pleasing shapes within the off-kilter frame.

“Flowers in a Vase,” 1905, by Olilon Redon

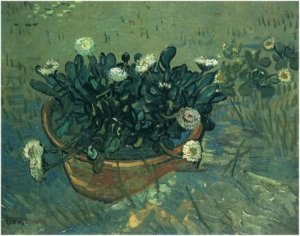

Vincent Van Gogh’s appealing “Daisies, Arles,” 1888, is hung against a slate blue-green wall, its charm lying in the artless way these most prosaic of flowers are tossed into the basket. Soft brushstrokes show the basket has been left on the grass as the gatherer attends to some other task. In 1887, Van Gogh wrote his sister that he had banished the “gray harmonies” of his earlier work by painting “almost nothing by flowers.”

“Still Life with Pascal’s Pensees,” 1924, by Henri Matisse

The poppy-red room, “Redon, Bonnard, Matisse,” was the final treat. Odile Redon’s mysterious and mystical flowers have long been a favorite. “Flowers in a Vase,” 1905, seem to merge with the shimmering background, unmoored, floating in space. Looking at this painting, it’s impossible to believe that the artist worked only in black and white until the turn of the 20th century.

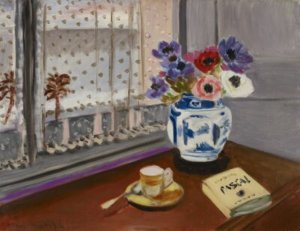

“Still Life with Pascal’s Pensees,” was painted in 1924 when Henri Matisse was living in Nice, France. The homey composition harkens back to the invitation of the Berjon painting with the open drawer and glimpse of seashells. This humble image, with none of the slick virtuosity of the Berjon, sent me a similar message: the connection between human thought and nature. Matisse may be about to sit down with his coffee, the breeze from the beach barely lifting the curtain, with his lovely blue and white vase of anemones, arranged just so, to be carried away by Pascal’s thoughts on human existence. Or maybe he’s just made that coffee for us, and we’re invited to join with him in contemplation.

“Wildflowers, Queen Anne’s Lace, and Poppies,” 1912, by Pierre Bonnard

Another favorite artist, Pierre Bonnard, painted early still lifes with floral motifs, and then, later in his career, came back to them and reveled in their delights. He made sketches in watercolor from life and returned to his studio to work in oil, thus abstracting complex details into an absorbing and brilliant composition. “Wildflowers, Queen Anne’s Lace, and Poppies,” 1912, is an exuberant explosion of color and light, in which the flowers in their tall vase seem spontaneously gathered, hardly labored over in the studio. (Thanks to Deborah Boschert’s Journal, “Around and About in Dallas,” for this image.)

We came out of this show dazzled, itching to draw flowers, in much the same way that seeing dancers leap across the stage makes you want to do grand jetes up the aisle of the theater.

I’m thinking of going back and making that sketch…I have until June 21. Join me?