And good-bye 2020. Universally deemed a dumpster fire or an unprintable act among consenting adults, the year hauled a lot of crap in its wake. But there were unexpected benefits, too. I slowed down. That was good.

Cheval Rouge, by Alexander Calder

As for my art rambles, once again, they’ve been cut short by rising pandemic numbers in DC. Fortunately, I was able to visit the sculpture garden several times this summer before it closed again in November. After months of seeing the sculptures behind bars, I was thrilled to be reunited with my old friends.

If you’ve been here, you likely have favorites, too. For now, though, come and say hello to mine.

Graft, by Roxy Paine

How can you not love Alexander Calder’s 1974 Cheval Rouge? With its four up thrust necks and five sturdy haunches, this big red horse invariably makes me smile. But then, I’m a huge Calder fan. The man was a genius, and, despite being widely known, his work has never become the cliché of say, Georgia O’Keefe or Frida Kahlo, so widely reproduced and found on everything from socks to tote bags. Don’t get me wrong, I love their work too, but it seems to have suffered from having become part of the pop vocabulary in a way Calder’s hasn’t. How can you not fall for a guy who says, “I like to make things that are fun to look at, that have no propaganda value whatsoever.”

Lurking just behind Calder’s red horse is Roxy Paine’s Graft, 2008-2009. This piece haunts me in a way I can’t fully explain. I first encountered a Paine “dendroid” outside the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth and was blown away. The thing vibrated in the hot Texas air and seemed oddly suited to that state, so full of enormous things, both manmade and natural.

Paris Metro Entrance, by Hector Guimard

Among the newest installations at the sculpture garden, Graft is equally jarring and seductive. I love the way the shiny branches stand out in front of the evergreen trees. Round knots dot the trunk and, after a time, we see that the sculpture has two halves, one stately and orderly in its progression toward the sky, and the other twisted and unruly. The two sides are held together in a kind of suspended animation – a graft – that fuses human kind’s urge to alter nature with its sometimes unexpected consequences .

Moving on, we’ll walk past Hector Guimard’s glorious Art Nouveau entrance to the Paris Metro, and, putting off coffee at the Pavilion Café until later, we come to an unexpected grove of trees, partially enclosed by a low stone wall. The pavement ends and we find ourselves walking on a forest floor. Here large rocks invite us to sit and contemplate the secret treasure of the garden, Marc Chagall’s ethereal 1969 stone and glass mosaic, Orphée.

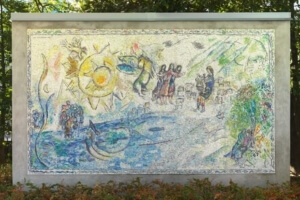

Despite its size and weight—ten by 17 feet and weighing 1,000 pounds—the piece appears delicate, shimmering in the shaded space. The composition centers on the figure of Orpheus charming animals with his lute, while the winged horse, Pegasus and the Three Graces float by him. Instead if a lute, though, I see Orpheus cradling the 2019 World Series Trophy won by the Washington Nationals. Maybe I’m just starved for baseball.

Orphee, by Marc Chagall

Anyway, in the lower left, a group of people wait to cross a large body of water. Is this the River Styx crossing to the afterlife? Later, I learned that the artist meant show the immigration of Europeans to America and also his own escape from Nazi-occupied France during World War II.

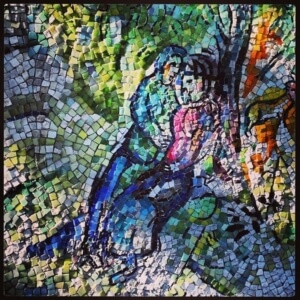

In the lower right, two lovers are sweetly entwined in a sylvan scene. Are they Adam and Eve? Orpheus and Eurydice? Turns out Chagall, on a 1968 visit to his DC patrons Evelyn and John Nef, decided to create this mosaic for their garden. There it lived until Evelyn donated it to the museum in 2009. When she first saw the work, Evelyn asked Chagall if the lovers were meant to be her and John. Chagall said, “If you like.” He must have been fond of these friends and patrons to show them in such a sweetly beguiling way.

Orphee, detail of lovers

Emerging from the grove, we see a huge typewriter eraser in mid-swipe, as if erasing the grass. Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s 1999 sculpture gives us an instant Alice in Wonderland feeling: suddenly we’re only inches tall. It’s such a funny, antique thing; does anyone even know what it is? Next time the garden is open, I plan to ask some young people. It’s likely only the odd typewriter collecting hipster will know.

Typewriter Eraser, Scale X, by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

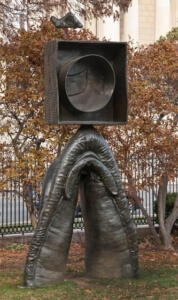

My last favorite is a new one to me. On other visits I’d somehow missed Joan Miro’s 1977 Personnage Gothique, Oiseau-Éclair, translated as Gothic Personage, Bird-Flash. I’d known Miro primarily as a painter, but this work—one of the largest—is among a number of sculptures he made after turning 70. Thoughtfully placed in front of two tulip poplars, the work suggests a figure with floppy cascading legs and a box for a body. The box contains a faintly traced image of a bird, and perched on top of the box is another bird-like element. Walking around the piece, the bottom half begins to resemble a shark, with its thrusting pointed nose, but the folds suggest leathery skin, very unlike a shark’s smooth body. There’s an echo of the Roxy Paine tree here: a structure both natural and man-made, a junction between the geometric box, the molten folds, and the caught image of the bird. Perhaps the bird has escaped its image in the box and is about to take wing? Whatever you see here, the piece is appealingly enigmatic, very much like Miro’s works on canvas and paper.

Personnage Gothique, Oiseau-Éclair, by Joan Miro

Unable to resist finding out more, I learned that Miro had cast a donkey collar and a cardboard box as the major elements. I never would have guessed, but then, I’ve rarely come across a donkey collar in my travels, being almost exclusively a city gal.

Now you’ve seen my favorites among the many treasures here. The gates are closed and I must content myself again with staring in through the bars. I’m told the gates will swing wide in March—another good thing about the coming year—and I’ll be free to visit my old friends. And have coffee at the Pavilion Café.

Hope you can join me.

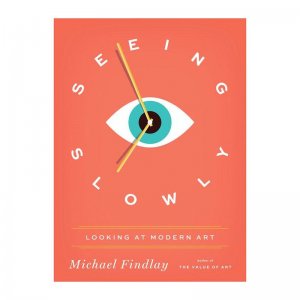

So, off I went again to the Mall, first stopping to sit on a bench, close my eyes, and breathe deeply for several minutes. (Step One in the Findlay method.) Next, I tried to let the art pick me (Step Two), rather than looking around for something “important,” or a piece by a well-known artist.

So, off I went again to the Mall, first stopping to sit on a bench, close my eyes, and breathe deeply for several minutes. (Step One in the Findlay method.) Next, I tried to let the art pick me (Step Two), rather than looking around for something “important,” or a piece by a well-known artist. At first, I saw only the enormous red-orange I-beams arranged at various angles, with one V-shaped piece dangling by a cable. As I gazed, words began to float up in my mind: forthright, masculine, audacious, thrusting, grounded. But that V. That V was oddly touching, hanging out there at the mercy of the wind, moving and changing as it turned. I noticed several other Vs in the composition and, as the light changed, the sculpture began to look like an enormous drawing.

At first, I saw only the enormous red-orange I-beams arranged at various angles, with one V-shaped piece dangling by a cable. As I gazed, words began to float up in my mind: forthright, masculine, audacious, thrusting, grounded. But that V. That V was oddly touching, hanging out there at the mercy of the wind, moving and changing as it turned. I noticed several other Vs in the composition and, as the light changed, the sculpture began to look like an enormous drawing. I circled the sculpture, all burnished and gleaming in the late-morning sun, I wasn’t sure how I felt about him. After about three minutes, a creepy sizzle from his eyes gave me the sense he was watching me. As I moved, his eyes followed. He seemed to say, with a leer, You have no idea who I am or where I came from, do you, honey? I shuddered. No epiphany with this guy, no communion, no awe.

I circled the sculpture, all burnished and gleaming in the late-morning sun, I wasn’t sure how I felt about him. After about three minutes, a creepy sizzle from his eyes gave me the sense he was watching me. As I moved, his eyes followed. He seemed to say, with a leer, You have no idea who I am or where I came from, do you, honey? I shuddered. No epiphany with this guy, no communion, no awe. I was relieved to move on and soon came upon two large shapes on a pedestal. Dappled under trees, this piece of abstract art sits overlooking the brooding Rodins in the Hirshhorn’s sunken sculpture garden.

I was relieved to move on and soon came upon two large shapes on a pedestal. Dappled under trees, this piece of abstract art sits overlooking the brooding Rodins in the Hirshhorn’s sunken sculpture garden. After three minutes of circling, I returned to the front of the sculpture. As I watched, the space between the figures began to vibrate and I swear I saw them move toward each other. The energy charge between the two creatures was electric. As I circled the sculpture again, it struck me that those shapes could never have taken any other shape that the ones they’d become. Broad and comforting, maybe male and female, maybe not, the pull they exerted on one another was palpable.

After three minutes of circling, I returned to the front of the sculpture. As I watched, the space between the figures began to vibrate and I swear I saw them move toward each other. The energy charge between the two creatures was electric. As I circled the sculpture again, it struck me that those shapes could never have taken any other shape that the ones they’d become. Broad and comforting, maybe male and female, maybe not, the pull they exerted on one another was palpable. So there you have my experiment in seeing slowly. I highly recommend trying it with the public art where you live. Fortunately for me, Washington, DC is blessed with a large quantity of outdoor art, and as I get more and more hooked on sculpture, I’ll return to this space with more slow observations.

So there you have my experiment in seeing slowly. I highly recommend trying it with the public art where you live. Fortunately for me, Washington, DC is blessed with a large quantity of outdoor art, and as I get more and more hooked on sculpture, I’ll return to this space with more slow observations.

The front view doesn’t enable one to foresee the back view. As you move round it, the two parts overlap or they open up and there’s space between. Sculpture is like a journey. You have a different view as you return. The three-dimensional world is full of surprises in a way that a two-dimensional world could never be.”

The front view doesn’t enable one to foresee the back view. As you move round it, the two parts overlap or they open up and there’s space between. Sculpture is like a journey. You have a different view as you return. The three-dimensional world is full of surprises in a way that a two-dimensional world could never be.”