She Who Tells A Story

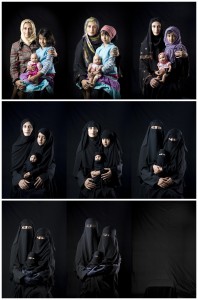

“Untitled,” from the Hijab/Veil series, 2011, by Boushra Almutawakel

I was drawn to this exhibit—She Who Tells a Story—at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, seeking revelations about life in the Middle East. The work (more than 80 photographs and a video installation) is part of the output of a women’s collective called Rawiya (“she who tells a story” in Arabic). Made up of women artists and photojournalists from Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Iran, and Jordan, the group endeavors to correct stereotypes about women in the region and about the region itself.

“Mother, Daughter, Doll,” 2010, by Boushra Almutawakel

As I walked from gallery to gallery, though, I felt I must be missing something. Many of the images seemed to reinforce stereotypical notions: the veil erases identity, women in Iran are voiceless, and war’s oppression has all but obliterated joy in the region. Could this be what the artists and curator intended? In preparation for writing this piece, I spent hours learning more about these extraordinary women. I was missing something—something rich, varied, complex, and rewarding. Taken as a whole, Rawiya’s work offers a vibrant glimpse into the complexities and rewards of day-to-day life in Iran and the Arab world. I wish the curators for this exhibit had chosen to mount a more representative selection.

Yemeni photographer, Boushra Almutawakel explores the hijab in her series “The Hijab/Veil.” She approached this subject with some trepidation, freighted as it is with controversy and potential for misinterpretation. But after 9/11, the artist saw that Muslims were being “demonized,” or “romanticized” by the Western press, and she decided to explore the topic. I felt an immediate connection to the fresh, open face of the young woman wearing an American flag as a headscarf. Although the artist worried that some Americans might find the image disrespectful, I didn’t see it that way at all. The girl seems to say, “Here I am, take me or leave me, I’m so much like you.”

“Metro #7,” from the series, “The Metro,” by Rana El Neuer

Another in the “Hijab” series, “Mother, Daughter, Doll,” 2010, shows Almutawakel herself with her young daughter. As each becomes more and more covered, their spontaneous expressions of joy seem gradually to fade, until, in the last panel, they are extinguished altogether. About this work, the artist says that veiling, taken to an extreme, or for political purposes, can become a dangerous way to control women and has “nothing to do with Islam.” Indeed, she faced withering criticism for using her own image in this work, an act considered unseemly in her increasingly conservative country.

From the “Women of Gaza” series, 2009, by Tanya Habjouqa

Rana El Neuer’s series, “The Metro,” reminded me of Walker Evans’s candid subway series taken in the 1940s. This artist, born in Hanover, Germany and now living in Cairo, created the work to “reflect rapid changes…in the middle class” in Egypt. The women portrayed appear wistful, alienated, or hidden from view, as in “Metro #7,” 2003. The wall text informs us that women are separated from men in Cairo’s subway cars; as the Arabic script over the doors attests. Gloom and despondency seems to haunt many of these faces, as they did in the Weston subway shots. In an interview about another exhibition, El Neuer said her Metro series also included pictures of men and she expressed mild concern that only showing the women’s images would distort the viewer’s perception of the piece as a whole.

“Aerial 1,” 2011, by Jananne Al-Ani

Tanya Habjouqa, born in Jordan and now living in in East Jerusalem, gives us modest pleasures in “Women of Gaza,” 2009. These images show everyday moments: picnicking, taking a selfie, doing aerobics, going for a boat ride. They are winsome, sweet, but also telling, given the restrictive environment in which the women live. In researching this artist, I found so much I wish had been included here. Habjouqa’s work is often surreal and slyly ironic, like the furniture salesmen sitting in brand-new chairs by an Israeli security wall, optimistically waiting for business to come along.

“Untitled #4,” 2008, from Gohar Dashti’s series, “Today’s Life and War.”

At first glance, Jananne Al-Ani’s large image, “Aerial 1,” 2011, appeared to be a rumpled bedspread embroidered with Ws. Up close, you see that it is an aerial shot of roads and structures. The artist, who was born in Kirkuk, Iraq and now lives in London, says the piece “…explores the disappearance of the body in the landscapes of atrocity and genocide and how it affects our understanding of the often beautiful landscapes into which the bodies of victims disappear.” Sobering, to say the least.

From “Today’s Life and War,” 2008, by Gohar Dashti

More war imagery is seen in Gohar Dashti’s series, “Today’s Life and War,” 2008. This staged series of photographs was taken on a film set outside of Tehran where the artist lives. Everyday actions—watching TV, celebrating a birthday—are portrayed by a couple of young actors in a surreal landscape of perpetual war. My favorites from this group—having breakfast in front of a tank and hanging out the laundry on barbed wire—bring the message home.

“Christilla, Rabieh, Lebanon,” from the 2010 series, “A Girl in Her Room, by Rania Matar

Switching gears, Rania Matar (born in Bierut, Lebanon, now living in Brookline, Massachusetts) shot the series “A Girl in Her Room,” 2010, to show “…the universality of being a teenage girl and the common bonds teen girls share – regardless of cultural differences.” I would have liked to see some of the photographs Matar took of U.S. girls in their rooms (also part of this series), if only to see that adolescent girls everywhere cocoon themselves in much the same way. A man standing near me in the gallery said to his companion, “These girls could be anywhere.” True. I love Matar’s Lolita-like Christilla with her challenging gaze. I could almost hear my step-daughter saying, all those years ago, “Don’t even look at me!”

Furniture Makers in the Town of Hizma, Palestine, 2013, by Tanya Habjouqa

Despite much in this show that is charming and revealing, I walked out of the last gallery feeling forlorn. Most of the exhibition’s spaces, if not all of them—certainly the largest ones— displayed devastating images of war: bullets, guns, bloody boots and high heeled shoes, a grenade in a bowl of fruit.

From “Women of Gaza,” 2009, by Tanya Habjouqa

I’m not saying that the region hasn’t been riven by war. Indeed it has, and, sadly, continues to be. I’m not saying that images of war aren’t appropriate here; undoubtedly, war has had an indelible effect on the region and its people, men and women alike. All I’m saying is that I wanted more balance in the curators’ choices. For me, their emphasis fails to give the viewer the fullness and humanity of Rawiya’s work.

I’d love to hear what you think, if you can make it to see the show—up until July 30, 2016.

I saw the exhibit today, and I think you’re right about the selection of the photographers being a bit unrepresentative of Middle East women today. The hijab is not really an instrument of veiling and covering, but a display of femininity and playfulness, as important in alluring attention as a brooch or a scarf on western women (or a piece of clothing less concealing); it has gone way beyond the modesty it is supposed to represent, and yet many men are satisfied that it does represent an accepted modesty.

Too many of the photographs dwelt of the impact of war, feeding into the western perception that Arab and Iranian society is in a state of permanent war and that the region as a whole is too dangerous to travel to. To some extent you can expect that — in Palestine, for instance, where the Israelis never let the Palestinians think otherwise — but I would guess that in Iran, which hasn’t been at war for a long while, it is a political statement. Iranian movies today portray a rich and engaged youthful populace, whose furthest thought is war.

The series of photographs of girls in their own rooms basically concerns rich girls who can afford their own rooms. Most girls (and boys for that matter) are forced to share rooms with siblings and the dynamic of the room changes drastically. It is not personal space; it is common space.

The photographs from Egypt were few. The women in the Metro were strong and you could see the drama in the lives they had led, produced not by war but by mere survival or poor marriages. I’ve ridden in those metro cars a thousand times and it’s true I see a bleak face or two, but many women in the cars (i.e. in those cars not especially reserved for them, which I couldn’t enter) are laughing a joking with their girlfriends and boyfriends. The metro in a sense has become a place where boys and girls can meet and interact/flirt. The many older women who enter the cars I was in were almost immediately given a seat, as were any woman who showed signs of being pregnant.

What I miss most in this exhibit was the interaction that all sexes have with each other or with their own sex. People are rarely alone and people often are willing to listen to each other and even help each other.

Thank you for this, Terry. Your perspective is very welcome. I don’t think this show represents the fullness of the photographer’s work which did indeed show the interaction that is missing here. Hoping for a fuller retrospective of each woman’s work in the future.